THE STRANGE CASE OF DR JEKYLL & MR HYDE & COUNT DRACULA & DR FRANKENSTEIN & MR GRAY

Monsters of the nineteenth century

That great writer, Robert Louis Stevenson, was an immeasurable loss to academic Psychology. For one thing, he published his Chapter on Dreams in 1892, almost a decade before Sigmund Freud’s own masterpiece, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). His most-famous novel, The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, describes psychic conflicts on the battlefield of one man’s mind. Some have read it as prediction of Freudian psychodynamics itself, which dealt with the identical thing. In fact, Stevenson and Freud probably read the same scientific journals at the same time. It is even possible that Stevenson was treated by no less a psychologist than Jean-Martin Charcot, who was Freud’s own teacher.[i]

Dr Jekyll is Victorian fiction’s best mad scientist. He discovers a new drug and transforms into a different person, one who embodies every criminal impulse. Hyde rampages all over gaslit, pea-souper London, committing crimes that are not only violent, but also suggestively sexual. When Jekyll speaks of Hyde, he is unable to call him ‘I’, but always ‘he’.[ii] At length, he loses control of his creation. The dilemma is impossible. Jekyll has no alternative to suicide.

Hyde was a perfect fit for the criminology of the period. Here is what one character has to say about him:

‘He is not easy to describe. There is something wrong with his appearance, something displeasing, something downright detestable. I never saw a man I so disliked, yet I scarcely know why. He must be deformed somewhere; he gives a strong feeling of deformity, although I couldn’t specify the point. He is an extraordinary looking man, and yet I can really name nothing out of the way... There is something more, if I could find a name for it. God bless me, the man seems hardly human! Something troglodytic, shall we say? […] or is it the mere radiance of a foul soul that thus transpired through, and transfigures, its clay continent?’[iii]

Evil has warped Hyde’s body. The terrible criminal has become his own warning sign. He bears ‘Satan’s signature’ with him wherever he goes. Stevenson occasionally refers to his ‘apelike’ look.

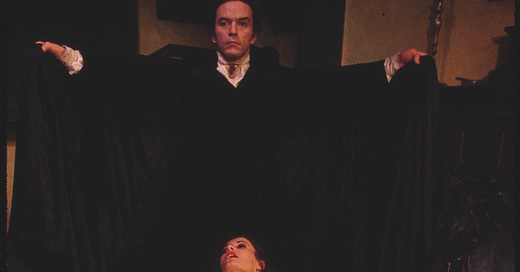

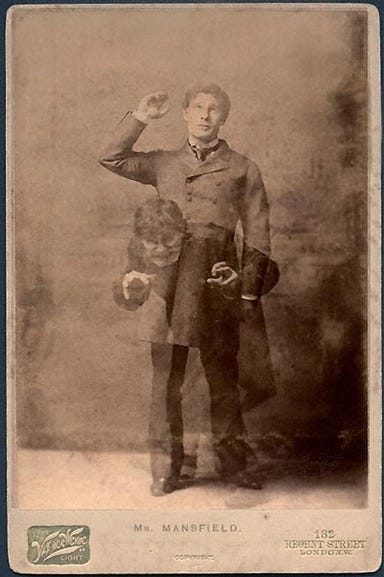

Richard Mansfield was best known for the dual role depicted in this double exposure: he starred in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in both New York and London. The stage adaptation opened in New York in 1887 and London in 1888.

It’s very common in fiction for criminals to look less good than heroes. Indeed, writers of fiction often use physical appearance as a shorthand guide to character. Walk in halfway through a crime film, and you may not know much about the plot, but you’ll be in little doubt who is the hero and who the villain. The answer is up there on the screen, looking right back at you. The reason is relatively simple, and it’s tied up with a psychological phenomenon called Social Identity Theory (SIT). I covered the theory in some depth in an earlier post.

The basic idea is that we all have two identities. Psychologists call them the personal and the social. The two are more or less independent.[1] Personal identities come out of our close relationships and our personality characteristics. Social identities…well, they can be more worrisome.

Everyone wants to feel good about themselves. Everyone wants high self-esteem. We can get it either through our personal identity – doing something significant, receiving praise for some small achievement – or through our social identity. Imagine a victory by a sports team that we happen to identify with, how good that makes us feel bout ourselves even though we contributed absolutely nothing whatever.

In the absence of victories by our team, though, we employ a different strategy. Instead of lifting ourselves up, we push the other side down. We are all interesting, good, moral, beautiful people. They, on the other hand, are dull, bad, evil, and ugly. Now we can feel good about ourselves again. Job done.

It’s worth stressing that this is not a conscious strategy (not usually, at any rate). Negative thinking of this sort seems to be an unconscious consequence of being in groups. Examples of groups are these: Human beings versus monsters; North versus South; civilians versus criminals; Us versus Them.

Jekyll and Hyde was one of a quartet of nineteenth-century novels that set the scene for modern horror fiction. The others were Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus (1818), Oscar Wilde’s The Portrait of Dorian Gray (1891), and Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). All three deal with the straightforward, intuitive idea that ugliness and evil belong together (They are bad; They are ugly). They also describe another nineteenth-century obsession: monsters, and what they mean.

Everyone fears monsters. Every culture has its own. We human beings are both their creators and their victims. This simple fact tells us something vital about ourselves. Like criminals themselves, monsters embody whatever is reprehensible, disturbing, or just plain bad. We can learn everything we need to know, just by the way they look: ‘they act as visible embodiments of evil, by way of the idea that evil is a form of ugliness. If the evil spirit were to become visible, this is how it would look - as “ugly as sin” [...] We take evil out of its hiding place in the soul and display it for all to see’.[iv]

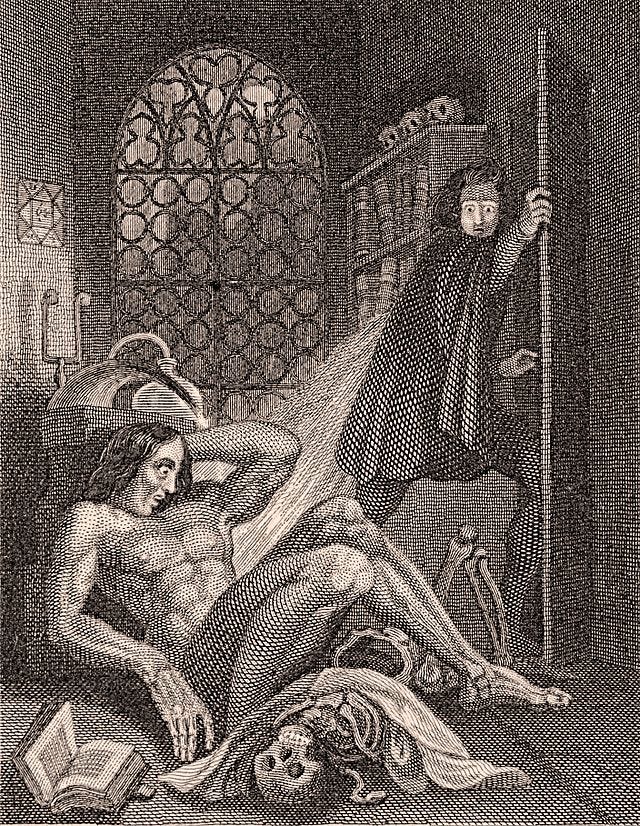

The authors of Frankenstein and Dorian Gray took the idea and twisted it into new shapes.

Frankenstein’s Creature begins as a virtuous soul who happens to be trapped in a body that signifies evil. His inner and outer selves are tragically mismatched. No one can help being frightened of him. Even when he tries to do good, people assume it’s evil. One glance and you know that the Creature is ‘not one of us’.[v]

Appearance is fate. The Creature becomes a monster on the inside for the simple reason that he looks like one on the outside. ‘I [...] bore a hell within me’,[vi] he complains.

Dracula, from 1897, meanwhile, actually provides some name-checks. ‘The Count is a criminal and of criminal type,’ says the heroine, Mina Harker. ‘Nordau and Lombroso would so classify him’. You’ve got to love that bit.

Mina – so well informed! – is referring to a pair of criminologists, somewhat famous at the time. Max Nordau was a contributor to what was then called ‘degeneration theory’. Instead of evolving, as they should, and improving all the time, the human race appeared to be devolving, and doing the opposite. Nineteenth-century Nordau fretted endlessly about the century to come, because it would be bleaker by far than any that had gone before. (In actual point of fact, Nordau was proven right, but for the wrong reasons.) Degenerates, he thought, would be everywhere, frightening civilians with their asymmetrical faces, lop-sided heads, enormous ears, weird teeth, squinty eyes, hare-lips, webbed fingers… At least they’d be easy to spot, though, which would presumably make policing a bit easier.

Such physical marks were known as stigmata. That word will forever be linked to Mina’s second name-check, Cesare Lombroso, who was the founder of so-called Criminal Anthropology. He believed that criminals were throwbacks to earlier stages of human evolution. They were very easily distinguished from Us. Like Nordau, he believed that They simply looked different. Lombroso’s work inspired a not only a generation of early criminologists to dash into prisons armed with measuring-tapes and callipers, but simultaneously inspired a generation of printers to churn out atlases of criminal bodies and charts of suspicious ear types.

Indeed, Mina’s physical description of Dracula corresponds point by point with one of Lombroso’s descriptions of Criminal Man.[vii]

If you would like to know a bit more about Nordau, you can click here. If you would like to know a bit more about Lombroso, you can click here.

Just two months after Bram Stoker made his first notes for Dracula, along came Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Gray. Like Frankenstein, it tells the story of a Faustian pact. Dorian is impossibly handsome: so much so, that his friend, Basil, can’t resist the urge to paint him. In the studio, Dorian is reminded that good looks always fade. He promises his soul if only the portrait will age instead of himself. Sin destroys beauty, and Dorian is planning epic, endless sin. No time to lose, he hides the portrait in his attic and gets started. He bounces around between two different Londons: polite society and an underworld of ‘monstrous marionettes’, ‘squat misshapen figures’.[viii] The hidden portrait becomes ever more hideous. Yet Dorian himself remains flawless as the model in a moisturiser ad. Basil learns his strange secret. Dorian kills him. He tries to put his life to rights but it is as if he’s mixed the pieces from different jigsaws. Goodness is no longer an option. Dorian takes a knife to the portrait and immediately collapses. His servants find the portrait miraculously restored to youthfulness but the corpse beside it ‘withered, wrinkled, and loathsome of visage’.[ix]

It’s the mirror-image of Frankenstein. Dorian Gray – the Creature turned inside out - is bad on the inside but looks good on the outside. His face is a beautiful mask that hides the evil behind. Morally, he becomes uglier by the moment. Towards the end of the book, he explicitly refers to the portrait as his ‘soul’, telling Basil that he is going to see ‘the thing that you fancy only God can see’. It is as if a bad life – a criminal life – is an ugly life.

Dorian also recalls Henry Jekyll. Although he gives rein to his vilest instincts and desires, no one ever suspects him, because his stigmata are hidden. In Jekyll’s case, they hide inside the body of his well-named alter ego; in Dorian’s, they hide inside the picture frame. In fact, Jekyll comes to a similar end. Two characters break into his laboratory, where they find Hyde’s body. He has died ‘thinking like Jekyll and looking like Hyde [...T]he secret sin (or the Mark of the Beast, if you prefer) which he hoped to conceal [...] stamped indelibly on his face’.[x]

Monsters, like criminals, led ugly lives. Monsters, like criminals, were different from Us. Monsters came from Transylvania, a mad scientists’ workshop, or the shadowy attic. Criminals came from the slums and rookeries, the Fourth Ward, the wrong side of the tracks, places that lay outside Our experience. Monsters, like criminals, were the image of straight society in a mirror no one could resist studying.

In 1888, Jack the Ripper shocked a nation. The London Evening News remarked on the ‘fiend in human shape, such as Mr Stevenson describes, roaming about the metropolis’. The Pall Mall Gazette warned that the murderer might be labouring under the influence of too much Jekyll and Hyde. The Ripper’s apparent ordinariness made him difficult to catch – he resembled Jekyll when he was not being Hyde.[xi] Stevenson must have wondered whether he ought ever to have written his great book. Less worried was Bram Stoker, who peppered his own novel with references to the murders. References to mythology, too, and those sexy demoniacs who make their appearance in the form of Dracula’s uncanny assistants.

‘The uncanny’ was an entire area of research for early psychoanalysts. Freud was thoroughly interested.[xii] His theory of personality disorder was built around an idea called repression. It means pushing troublesome feelings down into the dark of the unconscious. They don’t much like it there (who can blame them?) and sometimes act up. What we call the uncanny, Freud reasoned, is the resurgence of such feelings. Not knowing that they belong to us, we transform them into agents in the outside world. At one time, people might have called them demons, but today, we’d be more likely to think of aliens, which are more in tune with our modern mythologies. They’re the same thing: it’s just that the modern imagination finds ‘greys’ in the night-time bedroom that much more acceptable than succubi and incubi.

After a failed experiment writing under a different name, the horror novelist Stephen King published his own version of the Jekyll and Hyde story. He called it The Dark Half. It told of a horror novelist terrorised by his own alter ego. It turns into a psychopathic criminal named George Stark. The name refers to the pseudonym used by the crime novelist Donald Westlake for a series of novels about a psychopathic criminal named Parker. In between novels, Parker literally changes his face. But not even plastic surgery can hide the criminal inside. Even with his new face, Parker ‘looked like a man who’d made money, but who’d made it without sitting behind a desk. The new face went with the rest of him as well as the old one had’.[xiii] Lombroso would have approved just as much as Stevenson.

All pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also so that you can chase up anything you happen to find particularly interesting.

[1] There is a minor distinction to be made between Social identity Theory and Self-Categorisation Theory, but it’s one we can ignore for present purposes.

[i] Harman, Claire: Robert Louis Stevenson – A Biography, HarperCollins, London, 2005, p300

[ii] Stevenson, Robert Louis: The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Fugufish, Kindle edition, Loc1150

[iii] Stevenson, Robert Louis, op cit, Loc255

[iv] McGinn, Colin: Ethics, Evil, & Fiction, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, p144 (italics in original).

[v] McGinn, Colin, op cit, p147

[vi] Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft: Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus, The Marvel Comics Group, New York, 1983, pp117-125

[vii] Starr, Douglas: The Killer of Little Shepherds – The case of the French Ripper & the birth of forensic science, Simon & Schuster, UK, 2012,, p126

[viii] Oscar Wilde, quoted in Pick, Daniel: Faces of Degeneration – A European disorder, c1848-c1918, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993, p165

[ix] www.theguardian.com/books/2014/mar/24/100-best-novels-picture-dorian-gray-oscar-wilde

[x] King, Stephen: Danse Macabre – The anatomy of horror, Macdonald, London, 1992 p92

[xi] Flanders, Judith: The Invention of Murder – How the Victorians revelled in death and detection and created modern crime, Harper Press, London, 2011,, p435

[xii] www-rohan.sdsu.edu/~amtower/uncanny.html Accessed 5th April, 2017

[xiii] Stark, Richard: The Man With The Getaway Face, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2008, pp4-5

Here’s another one I’m too lazy to read today. But I also like the topic of monsters, where I have, I think, a kind of minority position. I’ll dig into this when a slot opens up, where my brain is functioning and I don’t have something else that’s pressing because I’ve been neglecting it.

Loved this post! I just bought this film at a flea market today and can't wait to see what it does with the Dr. J & Mr. H mythology.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr._Black,_Mr._Hyde