I’m told that the Italian language has no precise translation for the English word beauty. The word bella is as much a moral judgement as an aesthetic one. Italians, perhaps the best-presented, most style-conscious people in the world, are equally fascinated with good and evil (just look at all those churches). The concepts are twinned. Ugliness, too, is as much spiritual as physical.[i] This is worth remembering when we study Cesare Lombroso, the great criminologist who could hardly have grown up anywhere else.

Enrico Ferri, who was a prominent member of the so-called Italian School of criminology, wrote about the criminologists who came before:

“The theory of a free will, which is their foundation, excludes the possibility of the scientific question, for according to it the crime is the product of […] the human will. And if that is admitted as a fact, there is nothing left to account for. The manslaughter was committed, because the criminal wanted to commit it; and that is all there is to it.”[ii]

To any scientist in the nineteenth century, the Classical position seemed obsolete. This was, after all, the Century of Science. Everything must have its causes, and that included crime. Criminologists needed to find them.

Hardly anyone in science history has been so admired or so criticised as Ferri’s mentor. No textbook is complete without his name. Some love his work. Others dismiss it out of hand. They consider it an instrument of state repression, designed to help the middle-classes shrug off responsibility for a problem that was an inevitable consequence of the capitalist system.[iii] Whichever view you choose, Lombroso’s work was influential beyond measure.

It was singular for another reason, too. Scientific theories are usually developed over long periods, as an outcome of painstaking graft. Yet Lombroso’s arrived all of a piece, one day when he was performing an autopsy on the “famous brigand”, Vilella.[iv] On the back of Vilella’s skull, Lombroso discovered a deep depression. As he stared at it, he must have felt as if he were staring into the past:

“This was not merely an idea, but a revelation. At the sight of that skull, I seemed to see all of a sudden, lighted up as a vast plain under a flaming sky, the problem of the nature of the criminal – an atavistic being who reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and the inferior animals. Thus were explained anatomically the enormous jaws, high cheekbones, prominent superciliary arches, solitary lines in the palms, extreme size of the orbits, handle-shaped or sessile ears found in criminals, savages and apes, insensibility to pain, extremely acute sight, tattooing, excessive idleness, love of orgies, and the irresistible craving for evil for its own sake, the desire not only to extinguish life in the victim, but to mutilate the corpse, tear its flesh and drink its blood.”[v]

That’s the story, at any rate. It’s probably too good to be true. But all revolutions need their legends, and Lombroso was planning a revolution in criminology. In later life, he called Vilella’s skull “the totem, the fetish of criminal anthropology”.[vi] But if the skull had turned into something else, that was nothing compared to the transformation in Vilella himself. He had transmogrified in a way that that would do credit to a Hollywood screenwriter. The real Vilella was 69 years old and his body was twisted up with rheumatism. He died slowly from a cocktail of debilitating diseases. But in Lombroso’s imagination, he’d become a supervillain of “extraordinary agility”. Lombroso’s daughter, Gina, claimed that the stiff and wizened senior was, in his golden years, nothing less than “the Italian Jack the Ripper”.[vii]

Let’s be indulgent. Lombroso was a man who transformed his academic discipline as thoroughly as he transformed Vilella, so perhaps he was entitled to exaggerate. Celebrities often become victims of their own publicity.

Sometimes they become victims of their own theories, too. Lombroso was interested in the biological causes of behaviour, and certainly critics have accused him of failings that sound biological in turn: big-headedness, high-handedness, tunnel-vision. But who could blame him for his attitude, what with the future lit up before him like a vast plain under a flaming sky? It must have been distracting.

Early in his career, Lombroso measured 3,000 soldiers. He discovered that men from different parts of Italy had different physical measurements. This research allowed him to create new methods for identifying corpses. He wrote about the connection between homicide and pellagra, which is a disease that affects the physical appearance. He dissected the brains of patients who’d had mental disorders and was disappointed to discover no common physical flaws. That’s where Vilella came in. The head of Italian prison administration began to take an interest. Perhaps Lombroso had found a solid, scientific way to identify those Others who threatened the bold new Italian State, still just getting its engines warmed, still on the lookout for a compelling reason to exist. Soon, young Lombroso had access to all of Italy’s prisoners. He measured up to two hundred of them every year.

Lombroso’s theory made its debut in a book called L’Uomo Delinquente (which is usually translated as Criminal Man). The book went through numerous editions, from a pocket-sized version in 1876 to a shelf-cracking enemy of bookcases everywhere - a quadruple-decker - five editions and twenty years later. The early work is straightforward and easy to follow. The later is a dizzying dogpile of facts, statistics, and observations, held together by nothing “but the covers of the volumes themselves”.[viii] Among other delights, the book included an atlas of the criminal body, without which no criminologist ought ever to leave home. Criminal Man, you may notice, came out not so long after Darwin’s Origin of Species (1859).

Although Darwin did not know about genes, modern versions of his evolutionary theory tell us the genes that help build life occasionally, by chance, mutate. Most mutations die out. Others help the organism to prosper. Those mutations survive. Human beings may be complex organisms, but evolution implied that complex organisms required no Designer.

Some were scandalised. Others were thrilled. They suspected evolution to be the great engine of human progress. If, in the headlong rush forward, some had been left behind, perhaps that meant something. Perhaps criminals were “less evolved” than Us (whatever that was supposed to mean).

For Lombroso, then, criminals were simply made that way by evolution. They were modern “savages”, who’d evolved less far than Us. Crime was a straightforward biological fact. It was so biological that even certain plants might be considered “criminal”.

Enjoy this material? Why not buy me a coffee?

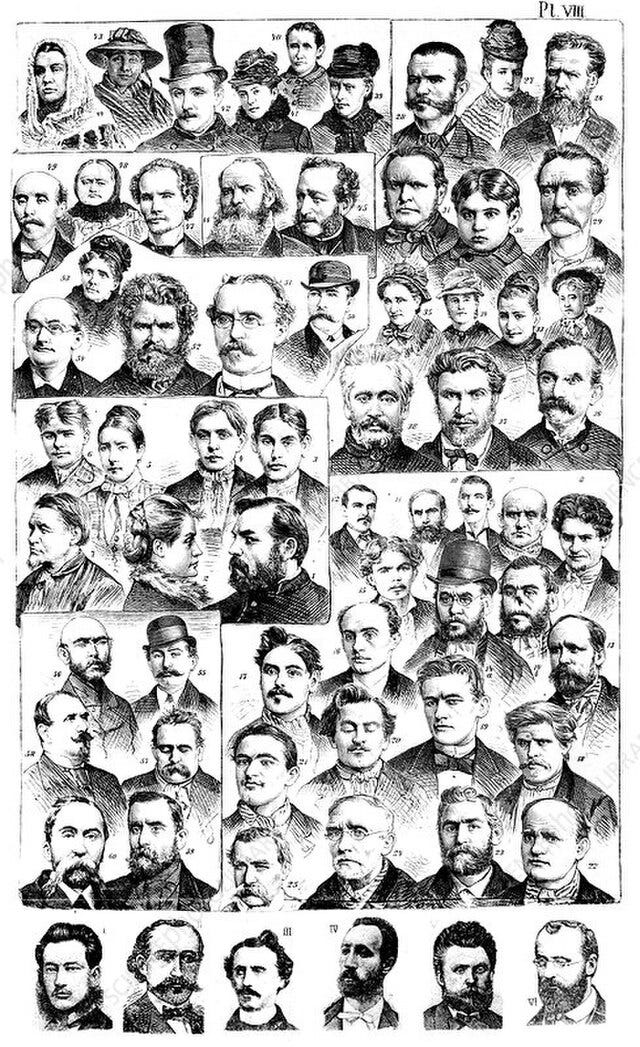

The illustration above illustrates various criminal ‘types’: Numbers 1-7 (centre left) are murderers. Numbers 8-25 (lower right) are burglars (14a and 14b illustrating a false nose). Numbers 26-38 (upper right) are purse cutters. Numbers 39-44 (top left) are shoplifters. The final groups (upper left and lower left) are forgers and swindlers. Across bottom are six bankrupts. This illustration is from L'Homme Criminel, a French edition of L'Uomo Delinquente.

That’s the essence of it. Yet it’s dangerous to understand Lombroso too quickly. Evolution was a force that affected even his own theory. It was like computer software - new versions were constantly appearing. There were add-ons, plug-ins, updates. At length, Lombroso’s Italian School incorporated social factors, like the cost of food, the effects of alcohol, police corruption, imprisonment, even climate.[ix] You will notice that they stuck to the important belief that crime did have causes. This idea was explicit in the title of one of Lombroso’s last works – Crime: Its Causes and Remedies.[x]

It’s clear that Lombroso possessed one of the most important virtues a scientist can have: the ability to change his mind when new information appeared. Of course, he had his vices, too. He could be terribly single-minded and dogmatic. He clung, for instance, to an outdated version of evolutionary theory called biogenetics.

Biogenetics says that, in the course of its life, every individual organism (plant or animal; you or me) passes through the evolutionary history of its entire species. Children, for instance, resemble early humans. Their looks are as primitive as their behaviour: “[T]he public believes that infants are angels, while they are nothing but savages”.[xi] To this, Lombroso added the idea of degeneracy. He’d learnt it from French criminologists. Rather than evolving, they claimed, some people appeared to devolve. Devolution might cause criminality.

Atavism was a related idea. Certain modern human beings seemed to have physical peculiarities that made them resemble “lower animals”.[1] Explorers of remote jungles claimed they’d spied human beings who looked like orang-utans.

Here is Lombroso summarising his theory: “Born criminals, programmed to do harm, are atavistic reproductions of not only savage men but also the most ferocious carnivores and rodents”.[xii] The criminal was “a relic of a vanished race”.[xiii]

That is the first of our two-part account of Lombroso’s theory. There will be more next week, Crime & Psychology fan! I know you can hardly wait! Relieve your frustrations by banging a blue button below! It costs you nothing but helps keep this newsletter in circulation.

All pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References given partly out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything you happen to find particularly interesting.

[1] This fascination should not surprise us if we remember that today’s anatomical knowledge is mostly rather new. Even in the first decades of the nineteenth century, surgery was struggling to differentiate itself from barbering. Today, we know that people from all walks of life are, more or less, created equal. As we saw previously, early anatomical knowledge came from dissecting executed criminals. No other cadaver was available to the surgeon. No one knew for sure that criminals and civilians were built the same way.

[2] “A surprisingly large number of auto-tattooists choose for the exercise of their dermatological art the chief motto of the British service industries, namely fuck off”.

[i] Jones, Tobias: The Dark Heart of Italy, Faber & Faber, London, 2013, p251

[ii] Ferri, Enrico: “Causes of criminal behaviour” in Eugene McLaughlin, John Muncie & Gordon Hughes (eds.) The Problem of Crime, Sage, London, 2001,, p53

[iii] Taylor, Ian, Walton, Paul, & Young, Jock, The New Criminology – For a special theory of deviance, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1973, p39

[iv] Soothill, Keith, Peelo, Moira & Taylor, Claire: Making Sense of Criminology, Polity, Blackwell, Oxford, 2002

[v] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina: Criminal Man According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso, GP Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1911, ppxiv-xv

[vi] Villa, Il deviante, p176, quoted in Gibson, Mary: Born to Crime: Cesare Lombroso & the origins of biological criminology, Praeger, London, 2002, p20

[vii] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina, op cit, p6

[viii] Horn, David G, Horn, David G: The Criminal Body: Lombroso & the anatomy of deviance, Routledge, London, 2003,, p5

[ix] Lombroso, Cesare: Criminal Man, trans. Mary Gibson & Nicole Hahn rafter, Duke University Press, Durham, 2006, pp316-324

[x] Lombroso, Cesare(3): Crime: Its causes and remedies, Little Brown, Boston, 1918

[xi] Gibson, Mary: Born to Crime: Cesare Lombroso & the origins of biological criminology, Praeger, London, 2002, p182

[xii] Lombroso, Cesare, op cit, p348

[xiii] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina, op cit, p135

This is great work! I am learning Italian (in part to read this material). Lombroso is really interesting. Lots to ponder here. I can see that there are attempts to formulate an archetype of sorts... in the biological sciences we see efforts to describe bauplans and even until recently museum and other places had exhibitions showing one of each kind... now there is a push towards showing variation within types..

Galton had some interesting ideas regarding people too, and he develop new techniques to try and create composite photo, so he could find common characteristics.