SIX CRIMINOLOGIES

Classical Criminology; The Italian School; Degenerates and Degeneration; Marxist Criminology; The New Criminology; Biopsychosocial Methods

You can think of the Classical Criminologists as reformers. An estate agent might describe the legal systems they inherited as fixer-uppers. They were harsh, arbitrary, and repressive. Some have claimed that their only purpose was political – they repressed the many while liberating the few[i]. By the era of the Enlightenment[ii], Europeans had lost their taste for archaic practices. Indeed, the very word ‘enlightenment’ makes a person think of what you see at the end of a tunnel. Enlightenment philosophers were great promoters of free will, autonomy, rationality, conscious decision-making. In keeping with this happy spirit, criminologists like the Italian Cesare Beccaria (pictured below) and the Englishman Jeremy Bentham set out to design a new legal system based on pure rationality. Crime, they argued, was the outcome of conscious, wilful choice. Law-abiding citizens like you and me were those who had studied the statute books and decided – freely, consciously, and reasonably - that our best and most advantageous course of action was to obey the law. Criminals, meanwhile, had done the same but decided that crime was more rational. Perhaps they thought there was quick money to be gained via pickpocketing, for instance, or perhaps Easy Street lay on the other side of a large inheritance that only matricide could ensure. Punishment had a distinct purpose: to help rational people decide that the law-abiding path was the most sensible one to pursue. Punishment must be ‘public, prompt, necessary, the least possible in given circumstances, proportionate to the crime, dictated by the law’[iii]. One point there may confuse you: Why should punishment be ‘public’? The explanation is simple – every citizen should have the opportunity to witness the inexorable connection between committing a crime and getting punished. Such a spectacle would help them choose the righteous path. Any punishment over and above what was necessary to drive a rational person to that conclusion, was by definition cruel and unnecessary.

Now, Classical Criminology was far from perfect. Indeed, certain imperfections may already have struck you. One is the simple fact that it assumes every criminal to be a reasonable, rational actor, not unlike, say, Cesare Beccaria himself. That assumption clearly doesn’t apply to everyone. For sure it does not apply to those criminals who – for whatever reason – appear to lack free will. If Classical Criminologists focused on ‘the crime, not the criminal’, the Positivist (or Italian) School flipped the polarity. Suddenly, the focus was on ‘the criminal, not the crime’. This is another way of saying that they saw little point studying an abstract legal system when actual criminals were available by the hundreds. The Italian School dates to the nineteenth century, which historians sometimes call the Century of Science. True to their time, the positivists ditched concepts like free will and rationality in favour of something more sciency: determinism. This is the view that everything that happens in the universe (crime included) is part of an endless chain of cause and effect. There’s no way to break the chain: no way to escape. Criminology had to abandon its associations with philosophy and become a science. The great work in the Positivist tradition is L’Uomo Delinquente (usually translated as Criminal Man) by Cesare Lombroso (pictured below), published in 1876. We’ll look at Lombroso’s theory in some detail next week. In brief, the positivist outlook was mostly a pretty optimistic one: Simply find the causes of crime, eliminate them, and we could all move to the Big Rock Candy Mountains. The Italians disagreed with the Classicists about the purpose of punishment. There was no point trying to deter a criminal from committing a crime. They were after all that very thing - a ‘criminal’. The laws of science doomed them commit the crime. The best thing to do was lock criminals away where they couldn’t hurt the rest of us. The idea was called ‘Social Defence’. It has clear appeal to law-‘n’-order politicians of the right wing today – so it is a surprise to remember that members of the Italian School often came from the political left.

Degeneration theorists elaborated on ideas that came from the Italian School. Indeed, an important book by one of its pioneers, Max Nordau, came with a dedication to Cesare Lombroso. We might think of degeneration theory as the French cousin. Not that the family resemblance was quite as strong as you might expect. That’s because degeneration theorists were constantly disagreeing among themselvese. Even so, all of them owed a debt to a biologist named Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, who gave his name to the view that ‘acquired characteristics are heritable’. Lamarckism implies that a person who spends their life exercising and developing big muscles will have children who are equally muscular. In other words, the characteristic that the bodybuilder acquired during their lifetime is passed down to the next generation (lucky them)[iv]. By the same token, if another person fails to use certain body-parts (maybe they live in a sound-proof environment and don’t use their ears), they might ‘degenerate’. The children of such a person might be less lucky. The Comte du Buffon was a nineteenth-century scientist who picked up Lamarck’s idea and ran with it. All of biology, he thought, was on a downward slide, generation to generation. Every species was, in a sense, getting worse. Human beings were no exception. As our biology slipped, so crime-rates climbed ever skywards. It was alarming. Indeed, the degeneration theorists were unrepentant pessimists. Their miserablist ideas did not last long, in historical terms, although traces of them appeared in the literature for perhaps six decades. The biologist Paul Kammerer, for instance, expected American Prohibition to produce a generation of law-abiding teetotallers[v]. He could hardly have been more wrong. The Nazis, too, built the idea of degeneration into their own lunatic legal system[vi]. The horrors of Germany in the 1940s meant an end to degeneration theory. If it survives today, it is only in social-media name-calling by commentators on politics or the entertainment industry. ‘Degenerate’ one side sometimes calls the other, neither side apparently knowing quite what they mean.

Marxist criminologists aren’t. Karl Marx himself had relatively little to do with this approach to criminology. It was developed largely by his collaborator, Friedrich Engels, whose ghost might well be posthumously miffed about the whole lopsided deal. Or perhaps not - Engels had a lot of sympathy with a catchy slogan that was originally conjured up by the anarchist, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: ‘property is theft’. So perhaps his ghost might not mind so much. Incidentally, Marx often gets undeserved credit for that slogan, too. If property really is theft, the slogan is definitely Marx’s property. Marxist criminologists think of crime as a product of power exercised by the capitalist system. There is always a conflict involved when you have forces of production (that is, the means to produce goods that consumers want to buy) and social relationships between the bourgeoisie and their workers. In Marx’s time, you might say that the the conflict was degenerating. The forces of production had changed dramatically as a result of the Industrial Revolution, while the workforce was still organised along recognisably feudal lines. As capitalism advanced, resources were concentrated into the hands of fewer and fewer people. Such a position was unstable and untenable. Anyone could predict a riot – or a revolution. Capitalism, it is sometimes said, produces crime in the same way that a millinery produces hats. (Why Marxist theorist always seem to write about hats, of all things, I couldn’t say.) Marxist ideas were picked up by Willem Bonger, an important Dutch criminologist. Bonger took what some have considered a rather sterile approach to crime, making an in-depth study of the numbers that characterised crime rates in the late nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries. Crime, Bonger thought, was ultimately a consequence of capitalism and the egoism it instills in all its victims. This leads to a breakdown of sympathy along the lines of social class. The proletariat (working people) have no reason to feel sympathetic towards those who control the ‘means of production’. Indeed, they could not, since the capitalist system had an investment in keeping them ‘dehumanised’[vii]. After Bonger, there was little or no advance in Marxist theory until the 1970s, when it re-emerged in the form of American Marxist Criminology and, on the other side of the Atlantic, ‘The New Criminology’.

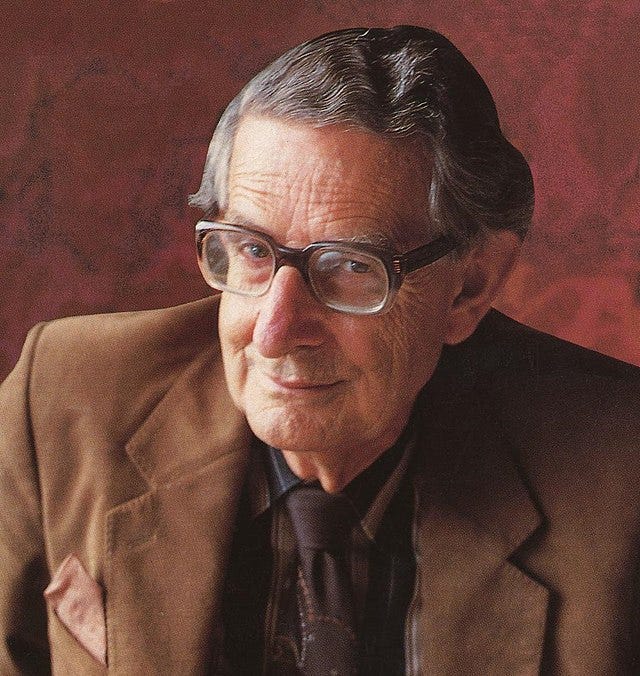

The New Criminology was partly a sociological response to an academic study that, by the early 1970s, was dominated by scientists who were trained in psychology or psychiatry. Such researchers (like the Italian School before them) were interested in establishing the causes of crime. These causes were often internal. That inevitably made it look as if the psychologists were simply trying to figure out ‘what was wrong’ with certain people they didn’t like. The psychologist Hans Eysenck (pictured above), for instance, had not long published a well-known book called Crime & Personality. Eysenck did exactly what you might think – tried to explain crime in terms of personality, which in turn was explained by individual biology. The New Criminologists thought this approach was fundamentally wrong-headed. They said that the behaviour of an individual could not be understood outside its political or economic context. Crime was socially constructed. Indeed, the very meaning of the word ‘crime’ was negotiable. In any negotiation, those who hold the power get to define the terms. ‘Crime’, then, was nothing more than whatever the people in power claimed it was. And by that phrase, ‘the people in power’, the New Criminologists knew exactly who they meant. You may have heard the phrase ‘the criminality of the state’. It may not have been original or unique to the New Criminologists, but they certainly seem to have popularised it. Their approach contains an element of what’s sometimes called labelling theory. Its roots lie in the sociology of the 1920s and 30s. Sociologists were traditionally interested in how certain kinds of behaviour ‘come to be understood as deviant’, and how the norms and values that are shared by all the members of a society contribute to that process[viii].

Positivist criminology hit some bumps in the last decades of the twentieth century. The period from the 1970s onwards belonged to sociologists. As we have seen, criminology was dominated by academics who emphasised social construction, labelling, the meaning of crime. But positivist criminology has had quite a renaissance recently. As much as anything else, this is the consequence of rapidly developing technology. Modern biopsychosocial methods allow us, for instance, literally to look inside the criminal brain. Biopsychosocial theorists speak about neuroimages, DNA, and genetics. Once again, these are individual variables rather than social ones. This is not simply a return to the mindset of previous centuries, though. Positivist criminologists of the nineteenth century couldn’t even have imagined what their descendants are doing today. The new approach is sciency and subtle. It jigsaws together elements from various related disciplines – psychology, medicine, neuroscience, biology. What all these disciplines have in common is a scientific methodology. The fundamental idea shared by biopsychosocial theorists is that crime has causes and that, using the methods of science, we can establish what they are. More on this in an upcoming newsletter!

In the meantime, please bash a blue button below. It costs you nothing but it sure helps me keep this newsletter going. Or think about maybe buying me a coffee! That’d be nice.

All pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References supplies partly out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything that particularly interests you.

[i] Foucault, Michel: Discipline & Punish – The birth of the prison, Penguin, London, 1991, pp1-72

[ii] By which we mean, approximately, the late 17th and early 18th centuries

[iii] Cesare Beccaria, quoted in Soothill Keith, Peelo Moira, & Taylor Claire: Making Sense of Criminology, Polity, Cambridge, 2002, p2

[iv] Toates, Frederick: “Biological perspectives” in Ilona Roth (ed), Introduction to Psychology, Volume 1, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd, East Sussex, 1993, p211

[v] Jones, Steve, No Need for Geniuses – Revolutionary science in the age of the guillotine, Little, Brown, Great Britain, 2016, pp312-4

[vi] Watson, Peter: The Modern Mind – An intellectual history of the twentieth century, Perennial, New York, 2002, pp294-5

[vii] Jones, Stephen: Criminology, third edition, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp244-5

[viii] Walklate, Sandra, Understanding Criminology: Current theoretical debates, Second Edition, Open University Press, Buckingham, 2003, p23

This is an interesting piece on the subject of the science behind crime and criminals. Its something that not many of us think of at that level, we stop at criminals, bad, lock them up, and throw away the key while we're at it.

Great post! I'm simultaneously thrilled to see someone write about this and bummed that it wasn't me!