SO YOU ARE PLANNING TO STUDY PSYCHOLOGY – TEN (OR MORE) THINGS YOU OUGHT TO KNOW Part 2 – Ideas you will need to master

Levels of explanation; reductionism; ecological validity; the branches of psychology

This week’s newsletter is aimed at two different groups of reader: those who are thinking about taking a degree next academic year, and those who are not. Either way, if you’re interested in Psychology, but just getting started on the subject, here are some vital concepts dear to the heart of psychologists everywhere but which sometimes cause confusion.

It works as a follow-up to last week’s newsletter, called SO YOU ARE PLANNING TO STUDY PSYCHOLOGY – TEN THINGS YOU OUGHT TO KNOW Part 1. You don’t need to have read that in order to read this one, but maybe you’d like a link anyway!

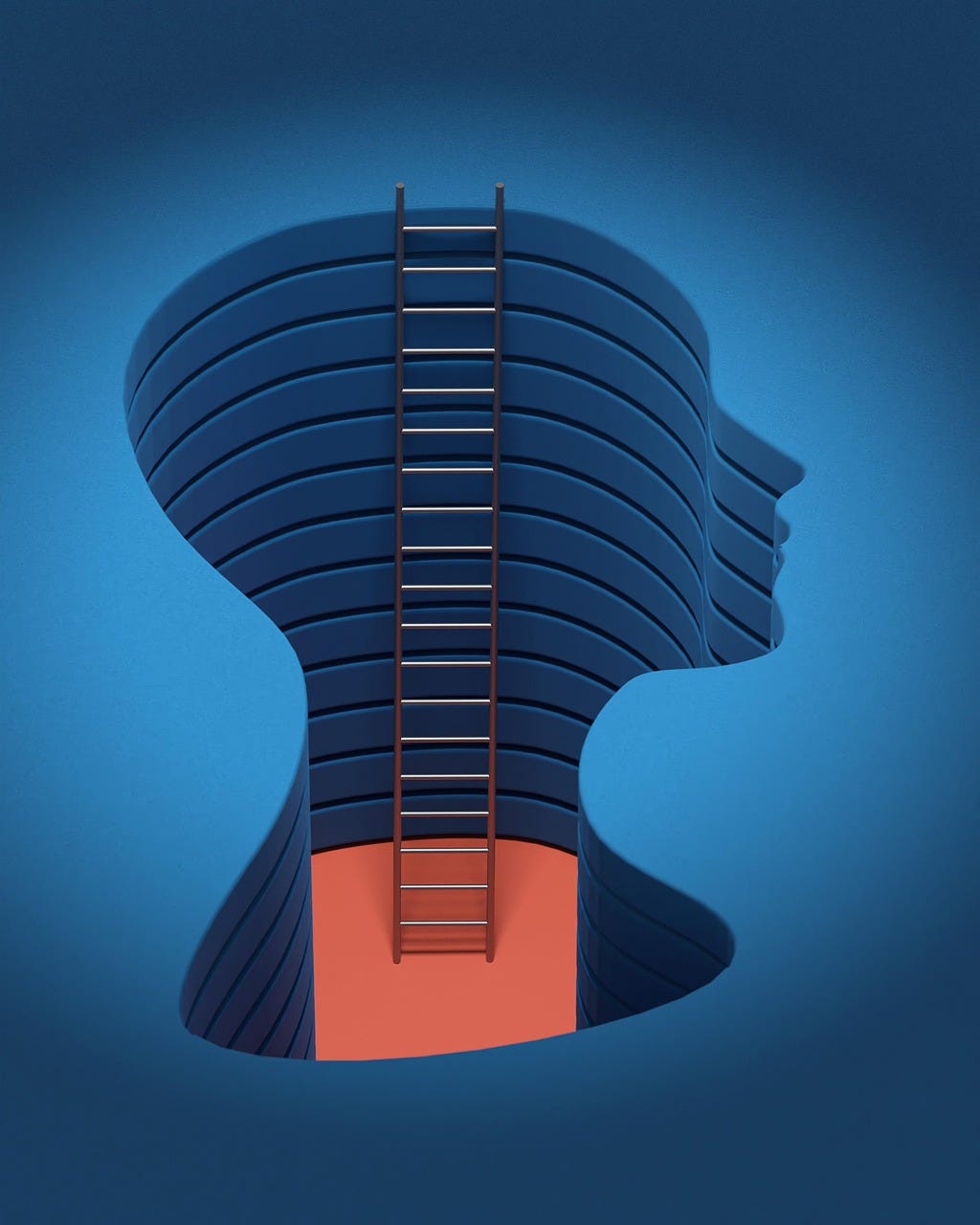

Levels of explanation

This may be the biggest stumbling-block to the public understanding of Psychology. Imagine we ask two psychologists, ‘What is the cause of crime?’ The first one, a specialist in cognitive neuroscience, says, ‘The cause of crime is over-activation of the brain’s limbic system, coupled with under-activation in the frontal lobes. This leads to an inability to control one’s impulses’. Meanwhile, his colleague, a developmental psychologist, gives a very different answer. ‘The cause of crime,’ she insists, ‘is lack of care and affection in childhood, which leads to insecurity in later life’. Which psychologist is right?

Of course, there is no need to choose. The two explanations, although very different, are not mutually exclusive. Both could be right, just one, or neither.

This is a lesson in ‘levels of explanation’. The term seems to have been popularised by the psychologist Paul Willner in 1985.[i] He gave a talk in which he asked this question: ‘Is depression a biochemical abnormality or an agonising subjective experience?’ The answer, naturally, is that it is both. The two explanations simply work at different levels. Neither cancels out the other.

Willner identified four such levels: biochemical; physiological; cognitive; and experiential. Which level we use to explain any given psychological phenomenon will depend on the kind of question we’re asking, and perhaps on our own training. All the levels interrelate. We might use drugs to treat depression. They would work by boosting the quantity of one of the brain’s neurotransmitters: dopamine, say. This is the biochemical level. Dopamine has the knock-on effect of increasing activity in certain areas of the brain (the physiological level). In turn we might hope that this would affect the patient’s thinking (the cognitive level) and thereby actually change their subjective experience of the world.

Different psychologists – not to mention different textbooks - may well identify different numbers of levels, or name them differently (One well-known psychologist looked at ‘ecological levels of analysis’ which have the individual in the middle, surrounded by larger systems such as localities, organisations and microsystems.)[ii] Ultimately, what is important is the concept. Don’t let someone tell you ‘We can explain all of human behaviour in terms of biochemicals’. That may be unwarranted reductionism.

Reductionism

This is, broadly, the view that the best level of explanation is the lowest one. In Psychology, the lowest level of explanation is likely to be that biochemical one. The idea is that complex phenomena are best explained by breaking them down into their component parts and seeing how those parts fit together (strictly speaking, this is called ‘structuralism’ although you won’t see the word in too many Psychology textbooks). For some psychologists, this is a very appealing point of view. Broadly, you’ll find that, the more sciency the background, the more reductionism appeals. One can certainly appreciate its seductions. Other psychologists might warn you against them. They argue that, as we move up through the levels of explanation (from biochemical to experiential) new phenomena emerge - ones that can’t be explained in terms of lower levels. The usual analogy is with ice turning into water. One is a liquid and the other is a solid. We can’t explain this everyday but bizarre phenomenon without referring to properties of H2O that emerge at different temperatures. Is the analogy convincing? Psychologists differ.

MORE FROM CRIME & PSYCHOLOGY

HANS EYSENCK’S THEORY OF CRIME

I’ve heard of a distinction between quantitative and qualitative research. What does it mean?

The nature of social science has changed considerably in recent years. That’s because of an ongoing controversy that we can trace back to the influence of postmodern philosophers like Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida. They are loved and loathed in approximately equal measure. Their scepticism about such phenomena as the existence of ‘truth’ and the value of the scientific endeavour has influenced the mindsets of researchers around the western world. It’s reflected in the appearance of qualitative research: a relatively new approach to social science. Rather than dealing with numbers and statistics - which researchers from a more sciency background might prefer - qualitative researchers focus on language and the meanings it creates. The idea is that there is nothing literally ‘out there’ in the world for science to discover, no ‘truths’ waiting patiently for us, or at least not of the sort that scientists tend to believe in. Rather, human beings create ‘truths’ via the language that they use (the technical term ‘discourse’). By analysing discourse, we can get closer to the construction of what we like to call ‘reality’. Notice all those scare-quotes? They get right out of hand the moment you start writing about qualitative research.

Ecological validity

In an earlier newsletter, I wrote all about the implications of this idea for Forensic Psychology. It is a major problem, in fact, for any topic in applied Psychology, whether you’re interested in traffic-calming, cockpit design, or the bystander effect. Applied Psychology is just that – applied. We want our results to work in the ‘real world’. There is no point, for instance, finding out some new phenomenon in eyewitness testimony and then discovering that it only ever manifests itself in the laboratory, never in the police station. The point is to know about real eyewitnesses in real situations. ‘Ecological validity’ simply means the extent to which our findings apply in the real world. Unfortunately, the more ecological validity our study might have, the less our control over the research. Laboratory experiments are absolutely vital for establishing the causes of human behaviour. They are able to do that because they are highly controlled. Sadly, though, more control generally means less ecological validity. Both qualities are desirable. The fact that they are in opposition is a major obstacle to progress. Meanwhile, understanding that fact is likely to prove a major boost to your grades.

The branches of Psychology

You may have noticed that professional psychologists pop up on podcasts, documentaries, news programmes, and who-all knows what else. They have something to say on every topic a journalist might want to cover, from hostage crises to drug addiction to art therapy to chimpanzees. This causes confusion amongst the public and no wonder. Many of these experts, incidentally, call themselves ‘behavioural psychologists’ and that causes confusion amongst, well, me. What exactly is a ‘behavioural psychologist’ supposed to be? I’ve never met one and neither, I imagine, has anyone else.

In any given Psychology department, someone who does research into working memory might rub shoulders with someone who studies ‘the social construction of meaning’ and a couple of world experts on lemurs. No wonder the oldest of the old-chestnut exam questions asks, ‘Is Psychology a coherent discipline?’ ‘Oh, yes, definitely,’ say some psychologists. ‘Oh, clearly not,’ say others, who are perhaps a little closer to retirement. ‘But who cares anyway?’

The philosopher, Thomas Kuhn, claimed that science progresses in terms of ‘paradigm shifts’, when suddenly everyone in the science starts doing things in a different way from before. Some say that Psychology requires a big old paradigm shift before it is ever likely to become coherent. Other say that it has already had several, which is why, in different periods of its history, Psychology has been dominated by various ‘schools’: functionalist; introspectionist; psychodynamic; behaviourist; cognitive… Certainly that would help explain the apparently promiscuous, kaleidoscopic nature of the subject.

Perhaps this entire debate is just a symptom of an entirely natural identity crisis in a relatively new discipline, or perhaps psychology will fracture and turn into twelve new ones. Either way, there is no doubt that you will find something to interest you a lot, even as other aspects of the subject will leave you cold. That’s how it is for everyone.

If you enjoy Crime & Psychology, I encourage you to show your support by clicking a blue button, or even buying me a coffee. You can do it here. Thank you!

Blender-face image from Pixabay. References supplied partly out of academic habit, but also so that you can chase up anything that sounds particularly interesting.

[i] Willner, P: Depression – a psychobiological synthesis, John Wiley, New York, 1985

[ii] Bronfenbrenner, U: The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press, USA, 2003