CRIME & PERSONALITY

Why low resting heart-rate isn’t a good thing; introversion – extraversion; neuroticism; arousal; chronic offenders; psychopaths

Here’s some Psychology that you can try for yourself:

Take the loudest, brashest, most outgoing person you know. Buy them four espressos. What reaction will you get? If you’re thinking, ‘They’ll start bouncing off the walls’, you may be forced to think again.

Alternatively, try the opposite. Try mixing an introvert with plenty of that popular depressant, chardonnay. What should happen?

In both cases, your friends may start acting out of character. The extrovert may appear to calm down, while the introvert starts dancing on the tables and kissing strangers. Let’s see why, and what it has to do with crime.

Today we are considering a theory assembled by the famous scientist, Hans Eysenck. Although he wrote many books (about 75) on many different topics, Eysenck’s gaze remained steady on the subject of personality. Indeed, one of the best-known tools in Psychology is the EPI, or Eysenck Personality Inventory.

Personality is a fascinating area for everyone. We all have an investment in it, after all. Psychologists, naturally, are keen to learn all about it: but how to study something so complex, abstract, and seemingly elusive?

One solution comes from statistics: a technique called factor analysis. Don’t let the word ‘statistics’ put you off. The basics are fairly straightforward. Psychologists take all varieties of habits and behaviours and ask which ones go together. For instance, we might discover that someone who i) always returns extra change in shops, also ii) always returns misplaced items they find lying around, and iii) refuses to cheat at games. Asked to characterise that person, we might use the word honest. That makes sense, because those behaviours are precisely what it refers to. The word accounts for the behaviours.

Equally, someone who is i) always on time for appointments might ii) never miss trains and iii) always submit tax returns promptly. We’d use the word punctual. Again, that makes sense, because the word accounts for the behaviours.

Honesty and punctuality are called traits. These two traits - honesty and punctuality - tend to go together. Not always, not every time, but more often than we’d expect by chance, honest people are punctual people. No great surprise there, perhaps, but it’s reassuring that factor analysis confirms what we probably suspect.

Now, to characterise a person who is honest and punctual, we might use the word conscientious. Once more, that makes sense, because it’s what the word means.

Conscientiousness is a factor. Just as traits account for behaviour, factors account for traits (you can think of it as a hierarchy). Factors are the building-blocks of personality. Our behaviour, criminal or otherwise, is ultimately a consequence of personality. Hence the title of Hans Eysenck’s book, Crime and Personality

.

A book about heredity, biology, and conscience, it struck some readers as a campaign for Victorian values. Some went so far as to call Eysenck a Nazi sympathiser.[i] (This was illogical as well as hurtful. Eysenck’s grandmother was murdered in a concentration camp.) Eysenck, though, seemed to suit the role of academic outsider. He called his autobiography Rebel With A Cause.

Eysenck’s theory is appealing as well as controversial. Appealing because of its common sense, cut-the-crap conservatism: controversial for exactly the same reason.

The idea was that human personality consisted of just two factors. They were called introversion-extraversion and neuroticism. Let’s see what that means.

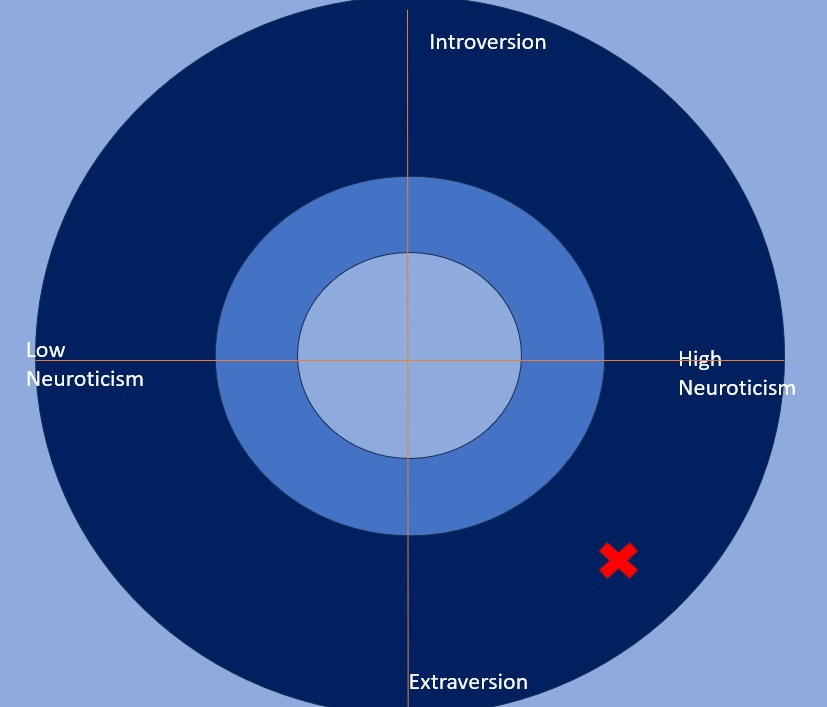

Picture each factor as a continuum, as in the diagram. They cross at right angles, which means they are independent (you can’t predict one from the other). Most people have a score somewhere in the middle of both continua, meaning they are in the light-blue part of the diagram. That’s probably where you are. The ends of the lines are thinly populated by the excruciatingly extraverted, the intensely introverted, the never-endingly neurotic.[ii] In the diagram, the darker the colour, the more extreme the personality.

Consistency is fundamental to the very idea of personality. Without it, there simply is no personality. Of course, everyone’s behaviour varies a bit from day to day. Friends and family sometimes surprise us by doing things we don’t really expect. Even so, they rarely do things we really don’t expect. That fact allows us to make predictions. If someone didn’t speak to the stranger at the bus-stop yesterday, she will probably not do so today, tomorrow, or next year. She has a particular trait, which causes her to act consistently. We might call it shyness.

This shy person, let’s make some more predictions about her. Soft music or loud? Wallflower or wisenheimer? The traits we call quietness and modesty often go together with the one we call shyness (again, not always, not every time, but more often than we would expect by chance). Together, they point to one of Eysenck’s factors: introversion-extraversion. Our shy person will be at the Introverted end of the line. Meanwhile, someone closer to the Extraverted end will be the opposite of shy, quiet, and modest. He may turn to crime. Psychopaths, for instance, are extremely extraverted.

Since this factor applies to everyone, everywhere, we expect human biology to be involved. Eysenck pointed to characteristics of the brain itself: inhibition and excitation. He didn’t use either word in quite the way we do in everyday life. That’s because he was preoccupied with learning. Excitation refers your brain getting into a learning state. It’s literally the readiness of the brain-cells to fire, and send information to other cells. Inhibition is the opposite: the brain protecting itself from learning unpleasant things.

To see what this means, imagine a car-crash. There are two classic responses. One victim says, ‘I don’t remember a thing’. There he was, whizzing happily up the motorway, and, next thing he remembers, he’s waking up in hospital. Everything else is blank. This victim has strong inhibition. He has prevented himself from learning. He may be happy to take a cab home straight away. He may even want to drive there himself.

But a second victim remembers everything. She’s haunted by the memory of the car crash. She dreams about it. It’s a torment. She may never want to drive again. This victim is an introvert, with weak inhibition. She learns far too well from experience.

The extravert is always trying to wake himself up. He may be keen on illegal drugs, joyrides, vandalism. Mischief helps fill what amounts to a hole inside. The introvert, on the other hand, is always trying to calm her over-active cells. She prefers quiet music to loud. She doesn’t speak to strangers. She likes gin-and-tonic, darkness, libraries.

That’s why our two friends responded so surprisingly to caffeine and alcohol. The extravert is chronically under-aroused. A megadose of caffeine makes him as jangly as an introvert. He calms right down, in an effort to lower his level of arousal. The introvert, meanwhile, is usually over-aroused, but the chardonnay lowers her arousal so she’s as under-stimulated as an extravert. She raises it back up by whatever means she can.

Some people are calm even in emergencies, whereas others panic all too easily. Eysenck wondered about the sympathetic nervous system, which controls our fight-or-flight response. It regulates the amount of sugar the liver releases for energy, the amount of clotting agent in the blood, heart rate, diameter of the pupils, and so on. It prepares us for action.

Like anything else in Psychology, nervous systems vary. Some are under-responsive. People with under-responsive systems tend to be cool, calm, collected. Those with over-responsive systems don’t.

Here’s a surprise: on average, convicted offenders have lower resting heart-rates than civilians. It is the single most reliable correlate of antisocial behaviour for any group you care to mention.[iii] Low heart-rates indicate low arousal.

Crime is a consequence of two things: first, those factors (introversion-extraversion and neuroticism); second, socialisation, or learning. How were we treated early in life? Did our parents reward us for following the rules, or punish us for breaking them? How well did we learn? The point was to develop a conscience.

‘People refrain,’ Eysenck wrote, ‘from careers of crime because there is in them a kind of “inner guiding light”, a “conscience”, a “superego”, which directs them to behave in a moral and law-abiding manner’.[iv] Yes, Eysenck was old-fashioned enough to believe that the conscience was important. No wonder he was unpopular.

Conscience is a matter of learning (actually, conditioning, to be technical, but we can safely ignore the distinction for now). Those who learn better develop a stronger conscience, and vice versa.

Neurotics learn poorly.[v] Hence they are unlikely to develop a strong conscience. The same goes for extraverts, who have the additional burden of constantly trying to raise their arousal. Hence they present a particular concern. According to Eysenck’s theory, a lot of offenders will find their personalities close to the red cross on the diagram.

Later, Eysenck added a third factor to his model: psychoticism.[vi] Psychotics are out of touch with reality. They are often cold and unfeeling; they may suffer delusions. They, too, learn poorly. No surprise they, too, often become criminals.

There have been various scientific studies of Eysenck’s theory. Results were, well, mixed. Even so, evidence mounted that raising a criminal’s arousal, in the direction of introversion, improved their behaviour. In fact, psychologists had suspected that since 1944, when a psychostimulant called benzedrine sulfate was given to a sample of so-called juvenile delinquents. In 1966, another group received amphetamines. Both groups appeared to become more law-abiding.

Across 37 different countries, extraversion and crime rates were found to go together. More extraverted populations committed more crime.[vii]

These findings slotted in neatly with Eysenck’s theory. So too does the fact that psychopaths and extreme extraverts just don’t seem to learn from experience in the way that you or I might. Hence they lack the strong conscience that keep us out of prison.

And yet…and yet we all know that plenty of introverts are in prison, and plenty of extraverts are not. How and why? The question brings us to a really fascinating prediction.

As we’ve seen, Eysenck didn’t claim that extraversion made you criminal, or that introversion did the opposite. Rather, he claimed that both had an effect on conditioning and, thereby, the conscience. We would usually expect a person’s conscience to have the ‘right’ contents. Civilian parents teach their children civilian values. Imagine, though, a case in which both parents are criminals. The mother is a prostitute and the father a thief (Eysenck’s example). Their child might be antisocialised. Rewarded for crime, he’d develop an anticonscience with negative contents. He’d feel guilty when obeying the law; virtuous when breaking it.

Such an effect would be stronger on the introvert than the extravert. Because he was poor at learning, the extravert would have a better opportunity to escape his criminal fate. This may explain the phenomenon of the quiet boy down the road whom nobody ever suspects, with the polite demeanour and the sock-drawer full of human livers. Eysenck himself uncovered evidence that murderers tended towards the introverted. In contrast stood the assassin – a very different class of criminal – often an extravert.[viii]

Image of Hans Eysenck courtesy of Wiki Commons. Image of his personality theory by the author.

References supplied partly out of academic habit; partly so that you can read more about anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Sheehy, Noel: Fifty Key Thinkers in Psychology, Routledge, London, 2004, p82

[ii] Eysenck, HJ: Crime & Personality, Paladin, London, 1970, p51

[iii] Portnoy, Jill; Chen, Frances R & Raine, Adrian: ‘Biological protective factors for antisocial & criminal behavior, Journal of Criminal Justice 41, 2013, pp292-299

[iv] Eysenck, HJ, op cit, p113; p121

[v] Raine, A; Venables, & Williams M: ‘Better autonomic conditioning & faster electrodermal half-recovery time at age 15 years as possible protective factors against crime at age 29 years’/, Developmental Psychology, 32, 1996, pp624-630

[vi] Eysenck, SBG, Eysenck, HJ & Barrett, P: ‘A revised version of the psychoticism scale’, Personality & Individual Differences, 6, pp21-9

[vii] B McGurk & C MacDougall; B Kirkcaldy & J Brown, cited in No Need for Geniuses – Revolutionary science in the age of the guillotine, Little, Brown, Great Britain, 2016, p423

[viii] Eysenck, HJ: ‘Personality theory & the problem of criminality’, in Eugene McLaughlin, John Muncie & Gordon Hughes, eds., Criminological Perspectives, Second Edition, Sage, London, 2003

Fascinating read, lots to ponder here about how traits/factors are measured and assessed and even how degrees of criminality are associated to other factors.