FORENSIC PSYCHOLOGY: EYEWITNESSES, AROUSAL, AND CRIME

Eyewitness performance; police interviews; cognitive arousal; weapon focus; bystander intervention; punishment

You are an eyewitness to a violent crime. Your memory immediately becomes a valuable commodity to lots of people, all of them strangers. The next few days will be busy ones for you. Police officers need to interview you; lawyers need to train you; judges need you to testify. Even journalists may want a turn. You are no liar, of course, and you honestly want to help the criminal justice system to the best of your ability. Even so, the question remains: how far can any of these people trust your account of the crime?

For most people, the intuitive answer is, pretty far. We’d expect to remember, say, an assault or a robbery with some accuracy. Events like that are surely as memorable as they are rare. Right?

You may already have recognised circular reasoning there. We expect to remember the event well because it’s memorable. How do we know it’s memorable? Because it’s the kind of event we’d expect to remember well.

In fact, there is plenty of evidence to indicate that memorable events like these simply aren’t all that, um, memorable. We often have more confidence in our memories than they deserve. A vast literature on the fallibility of eyewitness testimony proves it.

As long ago as 1908, two psychologists discovered one of the most influential and robust scientific laws in a science that, (let’s be embarrassingly honest,) doesn’t have all that many laws to boast about. They lent their names to one of Psychology’s most-mispronounced phenomena: Yerkes-Dodson. That name should be pronounced YER-keys, but rarely is.

For reasons best known to themselves, Yerkes and Dodson were doing research on learning ability in Japanese house mice. They found that mice learnt best under conditions of moderate arousal. Make the electric shocks too high and the mice were too stimulated to learn very well. Make them too low and they were not stimulated enough. As in everyday life, both stress and boredom were contra-indicated. Somewhere in between lay the happy medium and peak Japanese house mouse performance.

Now, you may not think that Japanese house mice are all that interesting. I would agree with you. You may not even be able to bring to mind quite at this moment an especially accurate mental picture of just what exactly a Japanese house mouse looks like. Once again, I share your pain. Extrapolate the findings to everyday human, life, though, and they start to become more intriguing, not to say intuitive.

The best conditions for performing any kind of task are when we are not too bored, but not too stressed, either. Very bored, and we start checking our phones, planning dinner recipes, maybe even just staring out of the window. Our workmanship suffers. Equally, try performing a task – especially a difficult one, even if you happen to be very adept – when highly stressed. You can predict what will happen. (This, incidentally, explains why so many perfectly-competent drivers fail their test. They’re simply too nervous to function well. It also explains why so many bridegrooms fluff their lines.)

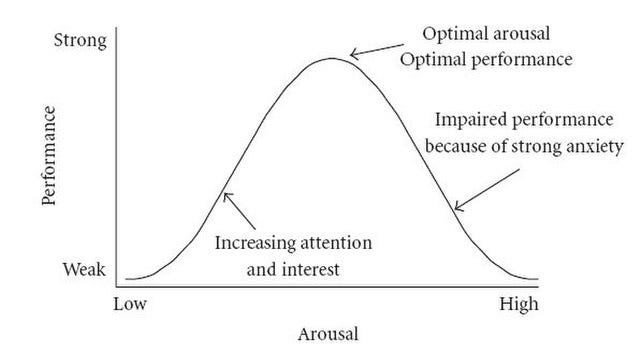

Stress can be either cognitive (worry; anxiety) or physiological (lots of adrenaline in the bloodstream; a pounding heart). It may be both.[i] The relationship between stress (in this context, psychologists call it ‘arousal’, partly because the word always gets a laugh in lectures) and task performance follows an inverted-U shape. Performance increases with arousal…until a certain inflection point, when it starts to fall off again.[ii]

This is true, at least, for complex or moderately complex tasks. For the most part, easy tasks seem to remain so, even under fairly stressful conditions (but try telling that to the driving student trying to get into first gear with the examiner in the next seat).

Here is the so-called Yerkes-Dodson curve as it is usually presented:

Certain tasks are very boring and we don’t tend to perform them very well. Imagine trying to put your grocery list into alphabetical order, for instance, or trying to learn Klingon for no reason. Under-aroused people rarely perform to the best of their ability. Now, imagine an interesting task: say, reading the latest Crime & Psychology newsletter. You find yourself somewhere near the top of that curve and your performance close to optimal.

Try to remember the details of an exceptional event like an assault or armed robbery, though, and you’re likely to move towards the right-hand side of the curve. You’re likely to be nervous, apprehensive, perhaps fearful. Task performance suffers. Add in the pressure exerted by an over-enthusiastic police officer, the unfamiliar, somewhat-unnerving environment of a police station, concerns about retaliation from the criminal in question, and you have a recipe for mistakes.

Some have argued that certain kinds of memory are special and don’t fit the Yerkes-Dodson law at all. They speak about so-called ‘flashbulb memories’. There is some controversy about the whole affair but to deal with it here would take us a long way off track. In fact, we dealt with in an earlier newsletter.

As a rule, with only a few exceptions, studies in forensic psychology seem to indicate a straightforward and quite intuitive relationship: The more serious the crime, the less well witnesses tend to remember it.[iii] That’s hardly surprising if we assume that more serious crimes imply greater arousal. Arousal, naturally enough, varies with violence, such that the more violent the crime, the worse the eyewitness performance. Perhaps eyewitnesses tend to focus more on the blood and the guns than they do on perpetrators’ faces.[iv] This is sometimes called ‘weapon focus’.

MORE FROM CRIME & PSYCHOLOGY:

WHICH UNITED STATES PRESIDENTS WERE THE MOST PSYCHOPATHIC?

EVIL & GENIUS; PICASSO & MATISSE

Eyewitnesses aren’t the only ones who suffer, either. Consider the phenomenon of ‘bystander intervention’. Sometimes witnesses to a crime dash into a phone box, change costume, and emerge as what the tabloid press likes to call ‘Have-A-Go Heroes’. Such thrilling behaviour is more likely under some circumstances than others. Again, the violence of the crime is likely to have an effect: the more violent it is, the less likely bystander intervention might be. Call it startlement, call it fear – psychologists prefer the phrase ‘physiological arousal’.

If you’ve ever had to testify in court, you’ll be familiar with the stress that comes with it. A court date is a daunting date, whether you’re a lawyer, an expert witness, or a member of the public who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. Indeed, court appearances are among the most stressful events in life. No wonder if witnesses’ memories become hazy, or their testimony less convincing than it may have been back in their living-room, when they were rehearsing in front of their significant others.

I’d like to add a wrinkle. It may have occurred to you to wonder whether some people are just chronically more ‘aroused’ than others. If so, you’d have a point. It doesn’t take a professional psychologist to notice that people vary in terms of many different characteristics, and ‘neuroticism’ is one of them. In fact, neuroticism is a measurable and enduring personality trait.[v] Let’s be clear what that means. Despite the name, neuroticism is not a clinical syndrome. It is simply one aspect of human personality: one that varies measurably between people. Neuroticism may be related to activity in a brain structure called the Ascending Reticular Activating System, or ARAS – which is just where you think it ought to be:

The famous psychologist, Hans Eysenck, dealt with this idea extensively. He also wrote a classic book on our subject called Crime & Personality, which you can read about here.

Eysenck argued that there was a simple equation at work when we try to assess how well someone will perform a task such as learning. Performance equals habit multiplied by drive:

performance = habit X drive

Emotion can act as a drive. People who are highly neurotic, then, can sometimes appear pretty driven. Again, this accords with our everyday observations: no one seems more driven that the extremely neurotic person who remembers she has left her bank card unattended. Relatively small amounts of input may be necessary to push neurotics past the peak of the Yerkes-Dodson curve, into the area where they start performing poorly. Under strong emotion, then, they may find it difficult to rectify or change their behaviour.

It’s the opposite for those who are chronically calm. They may well need input to push them up the steep left-hand slope.

Imagine using physical punishment - say, caning a naughty child at school - to try to rehabilitate some reprobate or other. Imagine too that the child in question is highly neurotic. Rehabilitation, of course, is really just a matter of learning – new habits, new ways of behaving, learning to obey the rules. If learning follows the Yerkes-Dodson curve, certain consequences naturally follow.

If our school child happens to be highly emotional or neurotic anyway, caning is hardly going to help. In fact, the pain is going to increase, rather than decrease, their emotionality. The child is certainly very unlikely to learn what his teachers want him to learn: indeed, the opposite is more likely.

Physical punishment might well be more effective on those who happen, as a matter of personality, to be less emotional (please don’t think I am condoning it. I am not.) It may tend to push them up that left-hand slope of the curve, to the point where they learn best. Here is Eysenck himself on this point:

‘[P]risoners and criminals generally tend to have s rather high level of emotionality. It would seem to follow that this emotionality would potentiate the antisocial habits which they have developed, to such an extent that they would find it far more difficult that normal, non-emotional people to supplant them with a proper set of habits. Punishment […] would, therefore, have a negative rather than a positive effect; it would lead to still greater rigidity in the reactions of the prisoner, rather than leading to any kind of change.’[vi]

I’ve pointed out in previous newsletters that we tend to spend rather little tax money training prisoners or teaching them socially-beneficial behaviour. We tend to have the common-sense view that punishment alone ought to be enough. Eysenck’s argument makes it clear why this strategy so often fails.

Eysenck was and remains a controversial figure in academic Psychology. His ideas are far from universally accepted. The same can be said for the Yerkes-Dodson Law itself. There is an alternative, known as Reversal Theory. Perhaps we’ll deal with it in a future newsletter. For the time being, Crime & Psychology fan, we can only wait for the next Sunday e-mail to find out what next week’s exciting topic will be.

Until then, please don’t forget to bang a blue button below and also buy me a coffee if you found this newsletter interesting.

Yerk

es-Dodson image courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. ARAS image courtesy of Pixabay. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything that looks particularly interesting.

[i] Deffenbacher KA: ‘Effects of arousal on everyday memory’, Human Performance, 7, 1994 pp141-61

[ii] Psychology anoraks will remind you that part of this formulation in fact comes from Donald Hebb, rather than Yerkes and Didson, but for present purposes we can ignore the distinction.

[iii] Hollin, Clive R: Psychology & Crime – An introduction to criminological psychology, Routledge, London, 2006, p155

[iv] Clifford BR & Hollin CR: Effects of the type of incident & the number of perpetrators on eyewitness memory, Journal of Applied Psychology, 66, 1981, pp364-70,

[v] Costa, PT, & McCrae, RR: The five-factor model of personality and its relevance to personality disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders, 6(4), 1992, pp343–359.

[vi] Eysenck, HJ: Crime & Personality, Paladin, 1970, pp155-6

In UK it can be a long time from offence date to charging a suspect. Then a long time to get to trial. What does that do to witness memory?

In aviation, my own specialty, a lot of mistakes are made after busy times (= high arousal). As things go easier, concentration can lapse.