EVIL AND GENIUS

Cinema; horror movies; projective tests; vampires; the nature of evil; painting; Picasso; Mailer; art

Do you sometimes root for the villain in a movie? Go one, you can admit it. Don’t worry about anyone overhearing. No need to say it out loud.

Sometimes we’re attracted to a villain. We may even identify with them. There’s nothing wrong with that, as long as we don’t become villains ourselves. Villains can be sympathetic sometimes, while heroes (whisper it) can be quite boring: annoying, even. I remember seeing The Blair Witch Project with a normally mild-mannered friend who actually shouted at the screen, ‘Oh, just kill them!’ Because the kids were so irritating, she’d ended up on the witch’s side. If you’ve ever seen the movie, you may well agree.

Alternatively, think about that icon of baddies, Dick Dastardly from the Wacky Races (Hanna-Barbera, starting 1968). You needn’t be a great fan of him (or his yappy sidekick, Muttley,) to find both of them infinitely preferable to their wishy-washy antagonist, that perpetual pain Penelope Pitstop.

‘Heroes,’ writes one journalist, ‘tend to have just one motivation: make the status quo better. But villains want all kinds of different stuff – money, power, fame, working out their anger. Villainous goals are nuanced in a way heroic goals have to be vague’.[i]

Vagueness – that’s just one of the many obstacles heroes have to overcome. Recent times have seen movie protagonists in particular swap traditional heroic qualities for a somewhat creepy partiality to self-righteous prissiness. They seem to buy too easily into the cultural consensus and spout slogans that you know the board-members and focus groups have approved (‘You've gotta do better, Senator. You've gotta step up’ says Sam Wilson at the end of Falcon & the Winter Soldier. For heaven’s sake). Supreme Intelligence, Sauron, and Lyutsifer Safin? At least they weren’t Captain Marvel, Galadriel, or even James Bond.

It’s all a matter of temperature. Even in the absence of a preachy antagonist, are certain villains just kinda cool? Is it the kind of cool that makes you feel warmly towards them? Or, if not exactly warm, at least less cold that you know, by rights, you ought to? The best villains surely do: it’s precisely in the emotional discomfort they stir that their dark power is located. Maybe you even have your own favourite, the baddie who makes your heart beat a bit faster when you know he or she is about to make an entrance. One friend tells me she always enjoys a villain who is suave and humorous (remember Mads Mikelson in Casino Royale). Me, I’m partial to the Joker. The devil, as everyone knows, does have all the best jokes.

And yet… To some people, the question doesn’t even make sense (never fear. We lost them at the first paragraph). Of course they’re never on the villain’s side! Virtue must not only triumph, it must be seen to triumph. What kind of monster would think otherwise? Raise the Villain Question in a polite gathering and watch certain other guest slink away with polite smiles and plans to talk to someone else instead. It doesn’t matter: you don’t want to be friends with them anyway. They’re boring. C’mon, be honest, who would you rather have over for dinner – smiley and polite Al Capone or that bad-luck magnet Eliot Ness?[ii] Count Dracula or that insufferable drip, Jonathan Harker?

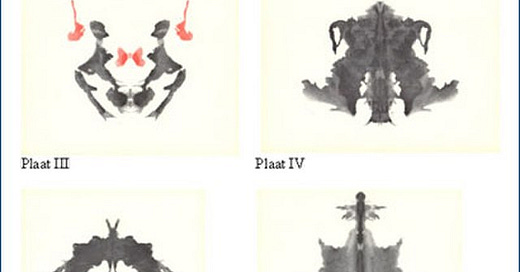

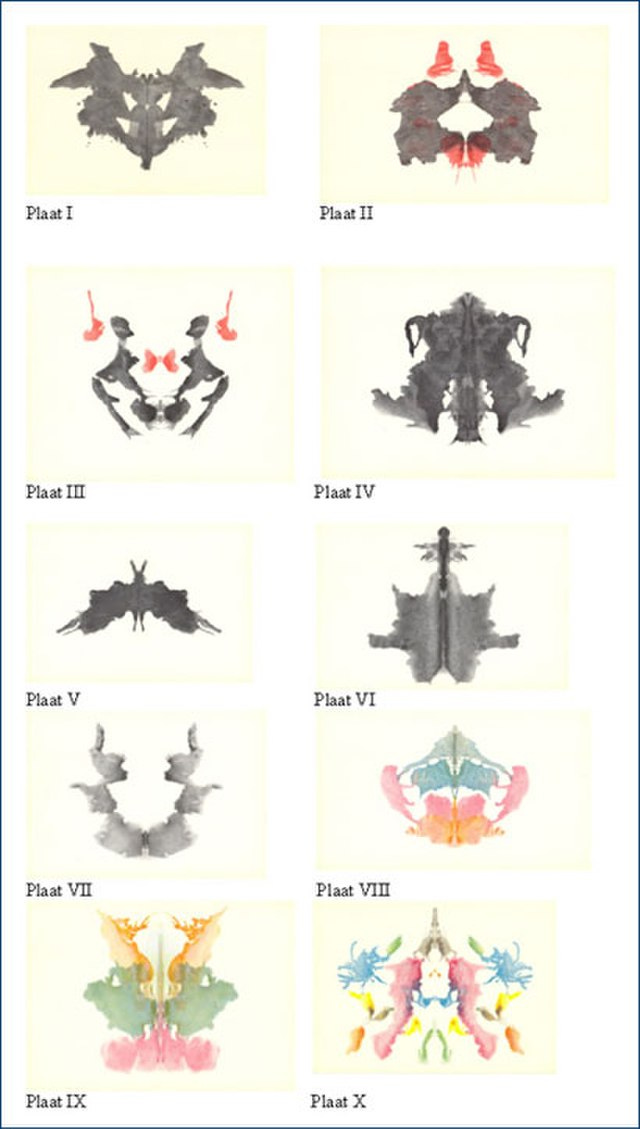

Surely, one’s taste in villains is liable to be as individual as one’s taste in film, or perhaps even more so. There are, after all, only so many genres of film, whereas villains… well, the spectrum of villainy is as wide as the desires of the human heart. Perhaps there’s even room for a psychological test along the lines of Rorschach ink blots. Let’s see how Rorschach ink blots work, or are meant to.

MORE FROM CRIME & PSYCHOLOGY:

VILLAINS IN 19th-CENTURY FICTION

As a schoolboy, Hermann Rorschach’s nickname was Klek, which means (of course!) Inkblot. Our young protagonist was forever drawing. His obsession found good use when he grew up to become a psychiatrist and develop his renowned ink-blot test. Klek’s simple idea was to tip a quantum or two of ink onto a card and then fold the card in half, thus conjuring up a virtually cost-free psychiatric instrument: a symmetrical pattern that (and this was the vital point) was known to be innocent of objective meaning. A Rorschach ink-blot belongs to the same species as the mirage. Psychiatric patients studied the empty images and reported what they saw. Their visions could have been construed in one place only – their own mind. (Technically, psychologists distinguish between top-down and bottom-up processing.)

In such a manner, Klek reckoned, a random pattern of ink on paper might provide insight into the contents of that mind itself. Imagine you and a friend studying the clouds. You see Dick Dastardly; your friend sees Penelope Pitstop. What does that tell you?

There is no need to wade into the deeper controversies of ink-blot history. Still, it’s only right to note that Rorschach’s test was dismissed for a long time as pseudo-science. That is, until it wasn’t.[iii] The test now occupies something of a limbo position, in western psychiatry at any rate, although I wouldn’t be rushing to use it if I were you.

Psychologists use the word projection. The patient is supposed to project their own world-view, the contents of their unconscious, or ‘cognitive schemata’, outwards onto the stimuli, whatever they may be. Instead of ink-blots, do you reckon villain preferences might work? Is villainy – in other words - a potential blank screen upon which a cunning scientist might make out diagrams of the psyche? Perhaps we could show patients an array of villainous faces and ask them to pick the ones they liked best (or feared most) and explain why.

Would the answers tell us anything? Maybe so. Surely an enthusiast for, say, Dr No, must be a very different person indeed from a fan of Shere Khan, the Dread Dormammu, or Walter White from Breaking Bad. Perhaps we might find commonalities among those who prefer killer clowns (Stephen King’s Pennywise; the Joker) to, say, corrupt imperialists (Gordon Gecko; Commodus) or misfit loners like Travis Bickle and Norman Bates.

Perhaps – and I’m merely speculating here – each category of villain might have its own internal structure. Among vampire-followers, we might expect to distinguish the morbidly Morbius from, say, the Spike-buffs of Buffy. Among the serial-killer crowd, a fan of Dexter might be very different from a fan of Hannibal Lecter. A rich mine of potential research indeed!

Here’s why I think it would work, whereas a test that involved picking your favourite hero might fail. A moment’s thought is all we need. Villains - let’s face it - are more fun, richer, more stimulating to the imagination. They come in all sizes, shapes, and types. Their motivations differ as widely as their physiognomies.

The same is not true for heroes. Fictional heroes tend to possess traits that bring to mind metaphors involving cookie-cutters. How different was Starsky from Hutch? Not so much that anyone could remember which one was which. You could exchange Kojak for Dirty Harry and save the props department money on the comb. Dick Tracy was swapped at birth with Philip Marlowe. The same actor might be believable as Superman, James Bond, or Bruce Wayne.

An interesting aside here: One of my undergraduate students carried out a piece of research asking whether we could predict ordinary people’s superpower preferences – invisibility or flight – based on personality traits. A fascinating piece of work, indeed, and what a pity the results failed to match the conception! Turns out you can’t.

You can quite understand why some people prefer a life free from villainy. For sure none of us want too much of it in our immediate future. Most of us just want to get on with our plans undisturbed. But drama… well, drama is something else. Drama can’t all be plain sailing. It requires more than a placid surface. Drama requires waves.

By its nature, perfection implies stasis. It cannot be otherwise. Perfection does not allow for disturbance. Indeed, if it anything at all does happen - if a breeze disturbs a lake – perfection is disrupted. A circle may be a perfect form but flatten it just slightly and perfection disappears like your fist when you open your hand. The quest – the hero’s task - is to still the breeze; fix the disruption; unsquash the circle. That’s what the hero’s for. That’s why actors are forever strutting and fretting and asking, ‘What is my motivation?’ Drama may require waves, but it also requires a character with the motivation to calm them. Without waves, without problems, we have no stories. Who wants to live in that world?

Villains are disruptors. They shake things up until stories come loose. What would Batman be without the Joker? Just some loser who keeps nipping out at night dressed as a flying mouse. Would you read his comic books? The poet John Milton must have felt awfully bored writing about Paradise. That’s why he lavished such attention on its opposite. Hell was simply much more interesting.

Of these two television serials, which would you prefer to watch?: one in which two characters competed to see who could be nastier, or one in which they competed to see who could be nicer?

The latter sounds pretty dull, doesn’t it? I wouldn’t care to watch unless you promised to get the Coen brothers involved. But I bet they’d opt to make the ‘nasty’ version. (If you sell this idea to Netflix, by the way, please make me an executive producer. I’d love to be an executive producer. I don’t know what executive producers do, exactly, but that’s no problem. Neither does anyone else.)

And so aesthetic matters enter the picture. The philosopher, Colin McGinn, makes an appealing case for the connection between aesthetics and morality. Good actions, he argues, are ones that have aesthetic appeal. That’s why we talk about ‘beautiful’ behaviour or virtues that are ‘good as gold’. The reverse is also true. Bad actions appear unaesthetic. Think of expressions like ‘ugly as sin’ or ‘foul act’.[iv]

Evil, to repeat, is naturally disruptive. Like ugliness, it consists in breaking the established order. When someone takes advantage of our good nature, or steals from us, we may feel as much offended as annoyed. It’s as if we’ve been gratuitously insulted. The flow of our life – its neatness and order, its happy attempts at symmetry – has been shattered.

Augustine of Hippo argued that evil was precisely the lack of something: a good quality gone missing. It corresponds to a painting with one corner untouched; a novel with the last page torn out. Thomas Aquinas had a word for that which was incomplete, or did not embody its proper form: ‘shameful’[v]. Evil is not an independent entity but a deviation from, or disruption of, that which ought to be.

You don’t have to be an apologist for criminals to prefer an imperfect world to a static one. You don’t have to be aesthetically blind to prefer an oil refinery to a forest or Jersey City to Tobermory. Some of the best people enjoy a bit of ugly. Take painters for instance:

Let’s go back to the early years of the 20th century. Leadership of the avant-garde had fallen into the seemingly-inappropriate lap of Henri Matisse….

Matisse no less! What a perfect spot to call a halt to this week’s newletter, sit down, and enjoy a picnic as we contemplate and discuss what we’ve learnt so far. Next week - refreshed in both mind and body - we’ll make the acquaintance not only of Matisse himself and his greatest rival – but also see why they feature in an essay about villains. Meanwhile, let’s amuse ourselves by bashing those blue buttons below. Go on, they deserve it. They’re villains:

Images courtesy of stickpng.com

[i] Hickey, Walt: You Are What You Watch – How movies & TV affect everything, Workman, New York, 2023, p47

[ii] Nickel, Steven: Torso – The story of Eliot Ness & the search for a psychopathic killer, John F Blair, North Carolina, 1989, p198

[iii] Mihura Joni L, Meyer Gregory J, Dumitrascu Nicolae, & Bombel George: ‘The validity of individual Rorschach variables: Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the comprehensive system’, Psychological Bulletin. Vol. 139 (3), 2013, pp.548–605

[iv] McGinn, Colin: Ethics, Evil, & Fiction, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999, pp144-7

[v] Thomas Aquinas, quoted in Umberto Eco, ed: On Ugliness, Rizzoli, New York, 2011, p15.

This reminds me of a discussion we'd have at work: why do girls like bad guys?.A few of the girls said good guys are boring, bad guys are exciting.

Reading Jason Frowley's post on villains is a delight. Heroes can be boring, and villains can be entertaining. But then there are the questions that arise when, over time, we see a flipping of the script. Jason makes Eliot Ness into a loose cannon and Al Capone into a smiling polite and therefore boring hero. When Eliot Ness was first introduced into popular television culture in The Untouchables (1959-1963) the personae were reversed. A stony-faced and well-groomed Ness led a squad of federal agents against the Italian mobsters who rose to prominence as the underworld aristocrats of the Prohibition Era. Maybe I'm going to have to go back and re-watch the series because I thought Ness was protecting society against the outlaws, a distinctly mundane policeman's job.