CRIMINAL WOMAN

‘The Female Offender’; Searching for the physical features that characterised female criminals; Criminology at the turn of the 20th century

Cesare Lombroso’s book, La Donna Delinquente, was published in 1895 (the English title was The Female Offender). In the twenty-first century, it can make shocking reading.

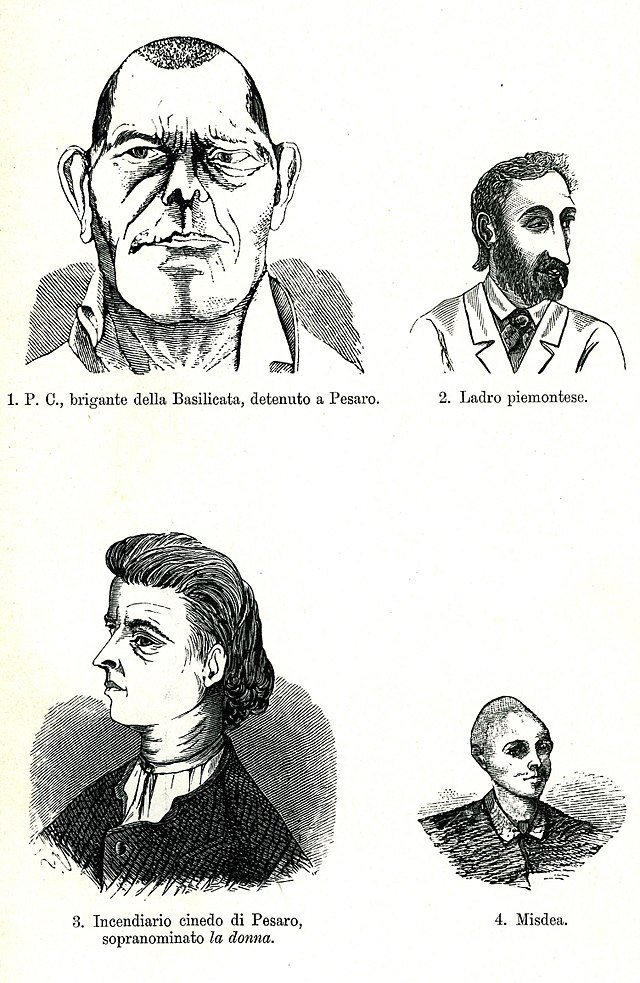

We saw in the last couple of newsletters how Lombroso argued that criminals were evolutionary throwbacks to earlier stages of human evolution. They did not behave like civilised nineteenth-century human beings and did not look like them either. You could easily recognise a criminal by his stigmata – that is, the physical features that distinguished him from his law-abiding contemporaries. Lombroso’s term was atavism – the idea that ‘primitive features’ could make themselves visible in modern human beings.

If you are one of those unfortunate souls who missed those last two newsletters, fear not! I have provided links. They are here and here.

You’ll noticed that I called the criminal ‘him’ in the paragraph above. That was deliberate. Lombroso’s earlier work was all about male criminals. Today’s newsletter, though, begins with his later work, on female criminals.

One of Lombroso’s predecessors was the splendidly-named Lambert-Adolphe-Jacques Quételet. He was one of the first people ever to apply statistics to crime. That’s a lot more interesting that it sounds, honest, and if you’d like to read more, you’ll be delighted to know that I have published a newsletter on the very topic. Just click here, but don’t forget to come back!

Quételet had already observed that women were generally less criminal than men. For most of us, that fact reflects well on women. For Lombroso, though, it did not. Lombroso was nothing if not counter-intuitive. Let’s see what he thought.

First, Lombroso suspected that women were less “evolutionarily advanced” than men. Oddly enough, this spelt danger for men. Since they were higher up the ladder than women, men could topple more easily, and had further to fall. Women were less likely to wobble. So Lombroso thought. Let’s say it now: This idea is plain silly.

Second, Lombroso wasn’t altogether sure that women really were less criminal than men. What about prostitution[i]? Surely, it tipped the scale towards women.[ii] The fact that prostitution was not a in fact crime in Lombroso’s Italy failed to bother him. Prostitutes were still “born criminals”, whether they committed crimes or not. Indeed, female criminals who were not prostitutes had failed even to commit their most “natural unnaturalness”.[iii]

Here are other things Lombroso had to say:

Rather few female criminals were atavistic. Among 286 prostitutes, Lombroso found atavism in only 14%-18%, as compared with 31% for males. “[W]e see the crescendo of the peculiarities as we rise from moral women, who are almost free from anomalies, to prostitutes, who are free from none”.[iv] Prostitutes sometimes had extremely small heads - about four times as frequently as “madwomen”.[v]

The news got worse:

“…if female born criminals are fewer in number than the males, they are often much more ferocious.

“What is the explanation? […] [T]he normal woman is naturally less sensitive to pain than a man, and compassion is the offspring of sensitiveness. If the one be wanting, so will the other be.

“We also saw that women have many traits in common with children; that their moral sense is deficient; that they are revengeful, jealous, inclined to vengeances of a refined cruelty.

“In ordinary cases these defects are neutralized by piety, maternity, want of passion, sexual coldness, by weakness and an undeveloped intelligence. But when […] piety and maternal sentiments are wanting, [...] it is clear that the innocuous semi-criminal present in the normal woman must be transformed into a born criminal more terrible than any man. […] [W]omen are big children; their evil tendencies are more numerous and more varied than men’s…”[vi]

Here, Lombroso was looking both ways: into the future as well as the past. When he claimed that women’s conscience was less well-developed than men’s, he anticipated one of Freud’s most controversial conclusions. When he warned about dangerous female sexuality, he anticipated twentieth-century noir fiction with its deadly flocks of femmes fatale. Perhaps I need not even mention that he harked back to the witch-hunts of the Early Modern period, too.

It is worth remembering that Lombroso was writing in an uncertain place, during uncertain times. Italy’s new political parties were fighting for power. Among them were fearsome feminists, who foretold who-knew-what nervous novelties. To Italian men, they were not just omens: they were threats; Enemies; Others.

Happily, Lombroso also wrote that “not one line of this work […] justifies the great tyranny that continues to victimize women, from the taboo which forbids them to eat meat or touch a coconut to that which impedes them from studying…”[vii] For a man of his time, Lombroso was pretty progressive. I dare say his daughters felt confident that he’d let them touch as many coconuts as they liked.[1] True, he hardly believed in gender equality, but then he’d probably never met anyone who did.

Female sexuality was especially scary. Everything seemed to point to it, including poetry, romantic novels, and department stores. Medics diagnosed nymphomania, caused by “morbid excitement of the genital organs”. Here was the typical nymphomaniac: “fleshy, well-developed muscles; average plumpness; black, abundant body hair; an expressive face […]; a large mouth with thick red lips; […] especially noticeable sexual parts”.[viii]

In 1835, well before Lombroso’s time, the also-splendidly-named Alexandre-Jean-Baptiste Parent-Duchâtelet had looked into the causal factors behind the sex trade. He was the first holder of the chair of medical hygiene at the University of Paris. Among other hygienic things, he examined prostitutes’ genitals. He failed to find the giant lips and clitorises he’d anticipated.[ix] They would have made perfect Lombrosian stigmata - external signs of internal lusts. Yet Parent-Duchâtelet did discover other, more plausible, causes. They included poverty, destitution, and family-members who depended on their mothers or daughters to provide food.[x] This was a sign of the criminology that was to come: more reasonable, more equal, less, frankly, scared.

Undaunted, Lombroso took up where Parent-Duchâtelet had stopped. He recorded that two percent of prostitutes had “exaggerated” pubic hair, 16% had “hypertrophy” of the lips, 13% had “enormous” clitorises, as well as narrow foreheads and abnormal noses.[xi] The fact is, even the best scientists sometimes find only what they expect to find, and no one has ever called Lombroso quite the best.

All of this seems pretty ridiculous these days. No wonder – we have better ideas. Criminology, however, doubtless had to pass through a ‘Lombrosian’ phase, just as the best and most reasonable adults have to pass through adolescence.

Even Lombroso himself seems to have recognised his crude limits. When criminologists mock his theory, they are usually referring to the very earliest version. Later in his career, Lombroso, that restless soul, got busy dealing with something much more sophisticated than what he had started with. Today we call it the nature/nurture debate. Lombroso stressed the concept of interaction.

I shall try to explain what this means. All human behaviour (however “biological” it may be) occurs in a social context. We are surrounded by other people; we are immersed in a culture. We use a language that we share with others. Everything we do is affected by both nature and nurture.

Neither on its own gives a full account of crime. This is easy to prove. A person could not become a criminal at all if they did not have the genes to develop a body, or brain. At least at that level, biology certainly has a role (nature). Similarly, that same person would never grow up at all without environmental input like food, water, air, etc. Environment must have a role, too (nurture). Clearly, criminality must be the result of interaction between the two. No psychologist would argue otherwise. What we do argue about, of course, is just what sort of interaction it is.

Later versions of Lombrosian theory all featured interaction. Environmental factors sometimes caused biological abnormalities. In turn, biological abnormalities sometimes affected the environment. Lombroso interested himself in all sorts of factors, including climate, diet, education, poverty, geology, and religion. He emphasised the importance of “insanity”, and epilepsy. Indeed, epilepsy could provoke atavism. Attacks could last up to two weeks, and have any effect you might dream of, from unstoppable letter-writing to desertion from the army.[xii] The criminal was both savage and sick.

Eventually, epilepsy became as crucial as atavism. When critics carped that only a tiny number of crimes were actually committed by epileptics, Lombroso’s answer was as ingenious as it was peculiar: hidden epilepsy. Indeed, he eventually claimed that even his so-called “born criminal” was just a special kind of epileptic.

By and by, Lombroso concluded that you could place people on a continuum, starting with law-abiding citizens and ending with atavistic criminals. In between came “occasional criminals”. There were several types. First was the pseudocriminal, who did honourable things that just happened to be illegal. Next came the habitual criminal and the criminaloid. Habitual criminals had poor education or upbringing. They might be drawn into the lifestyle of the Mafia, for instance, as a consequence of having been brought up in a Mafia-ridden environment. Criminaloids had criminal tendencies

but might not commit actual crime. It depended on their environment. Last came criminals by passion. They committed crime because of some emotional force they could not resist: “anger, platonic or filial love, offended honour…”[xiii]

You can see how Lombroso stressed the interaction of nature and nurture. At length, he concluded that only about one-third of crime was atavistic, perhaps even less.[xiv] Unfortunately, while atavism might account for only one-third of crime, today it seems to account for almost the whole of Lombroso’s reputation.

Around the turn of the last century, plenty of scholars were thinking about the environmental causes of crime. Émile Durkheim, for instance, liked to say that it was all society’s fault. So did the Italian socialist, Filippo Turati. Marxists like Willem Adriaan Bonger blamed the economy. Even Lombroso’s followers came to accept a philosophy expressed by the founder of the French School, Jean Alexandre Eugène Lacassagne: “Every society has the criminals which it deserves”.[xv] Yet the theories of Durkheim, Bonger, and Lacassagne all have one thing in common, something so obvious that it’s almost imperceptible: all assume that crime has a cause. Turati in fact made it explicit: “Remove the causes, and you remove the effects”, he said.[xvi] That’s the Italian School, right there. Please bang a bl

ue button below:

All images courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also so that you can chase up anything you find particularly interesting.

[1] This appears to be a Balinese taboo. Both women and coconuts are fertile, so the argument runs, hence a woman’s touch may drain fertility out of the coconut tree.

[i] The preferred term these days, of course, is ‘sex workers’. I quite understand the reasoning behind the change of terminology, but it seems not to fit in this case: after all, Lombroso was trying to emphasise the crime aspect of the phenomenon, not the work aspect.

[ii] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina, Criminal Man According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso, GP Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1911, p151

[iii] Pick, Daniel, Faces of Degeneration – A European disorder, c1848-c1918, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993, p105

[iv] Lombroso, Cesare & Ferrero, William, “The Criminal Type in Women and its Atavistic Origin”, in Eugene McLaughlin, John Muncie & Gordon Hughes (eds), Criminological Perspectives, Second Edition, Sage, London, 2003, p48

[v] Lombroso, Cesare, Criminal Man, trans. Mary Gibson & Nicole Hahn rafter, Duke University Press, Durham, 2006, pp56-7

[vi] Lombroso, Cesare & Ferrero, William, op cit, pp49-50

[vii] Lombroso, Cesare & Ferrero, Guglielmo: Criminal Woman, the Prostitute, & the Normal Woman, trans. Nicole Hahn Rafter & Mary Gobson, Duke University Press, Durham & London, 2004, p14

[viii] Archives de la Ville de Paris et du Départment de la Seine, Série D2U8, quoted in Shapiro, Ann-Louise: Breaking the Codes: Female criminality in fin-de-siècle Paris, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California, 1996, p127

[ix] Roberts, Nickie, Whores in History - Prostitution in western society, HarperCollins, London, 1992,, p228

[x] http://www.indiana.edu/~b357/texts/prosttn.html (accessed 17.02.14)

[xi] Roberts, Nickie, op cit, p229

[xii] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina, op cit, pp89-90

[xiii] Wolfgang, Marvin E: ‚Cesare Lombroso‘ in Hermann Mannheim (ed): Pioneers in Criminology, Patterson Smith, New jersey, 1972, pp232-291,

[xiv] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina, op cit, p8; Lombroso, Cesare, op cit, p223

[xv] Jean Alexandre Eugène Lacassagne, quoted in Rennie, Ysabel: The Search for Criminal Man, Lexington Books, DC Heath & Co., USA, 1978, p104

[xvi] Filippo Turati, quoted in Pick, Daniel, op cit, p148

Another wonderful column! The criminalization of sex is quite interesting when one sees the different behaviors that have been deemed as bad. You raise some really interesting points regarding Lombroso and his views on female crime.

I also wanted to engage with interaction. How determinist was he during his phase? Is Lombroso still advocating locking criminals up or is the interaction a way to redeem those who have committed crimes. I can see how this would be different for different kinds. Given his views, it would seem habitual criminals appear to be redeemable given that their criminal activities result from ignorance and poor environment whereas criminals by passion seemed harder to "cure." Did Lombroso argued that the frequency of atavisms were different in each category?

Female criminality is an interesting subject, and the impact of criminal acts perpetrated by women on our collective psyche seems much more daunting then by men since we are conditioned to think women are incapable of criminal violence. Either way, good read!