In our last newsletter, we looked at the basics of Lombrosian theory - that is, the very first ‘scientific’ theory of crime. Cesare Lombroso, we discovered, believed that criminals were throwbacks to early stages of human evolution. They looked different from civilians, and their behaviour was different, too.

Let’s start this newsletter by asking why appearance might be linked to behaviour. What did Lombroso think?

Imagine a time in which scattered human beings had to survive in hostile environments. Food was scarce; predators common. Psychological traits like dishonesty might have been useful. With limited food or shelter, it might occasionally make sense to steal your neighbours’. Aggressiveness, meanwhile, would help in the hunt, and help eliminate potential rivals.[i] Dishonest, aggressive people would survive. In nineteenth-century Europe, however, they’d probably commit crime. Their early-human appearance would give them away.

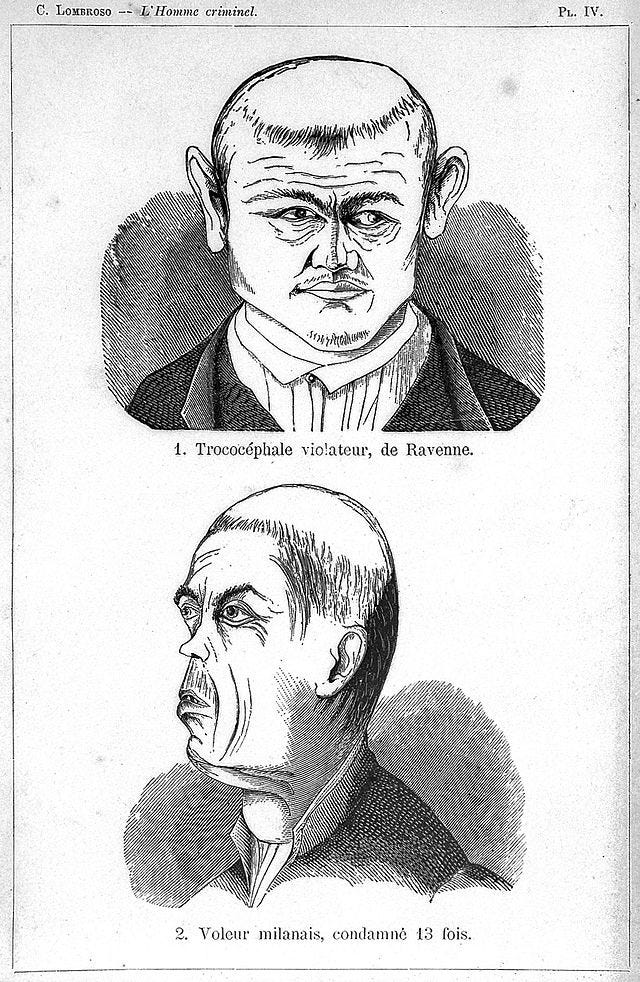

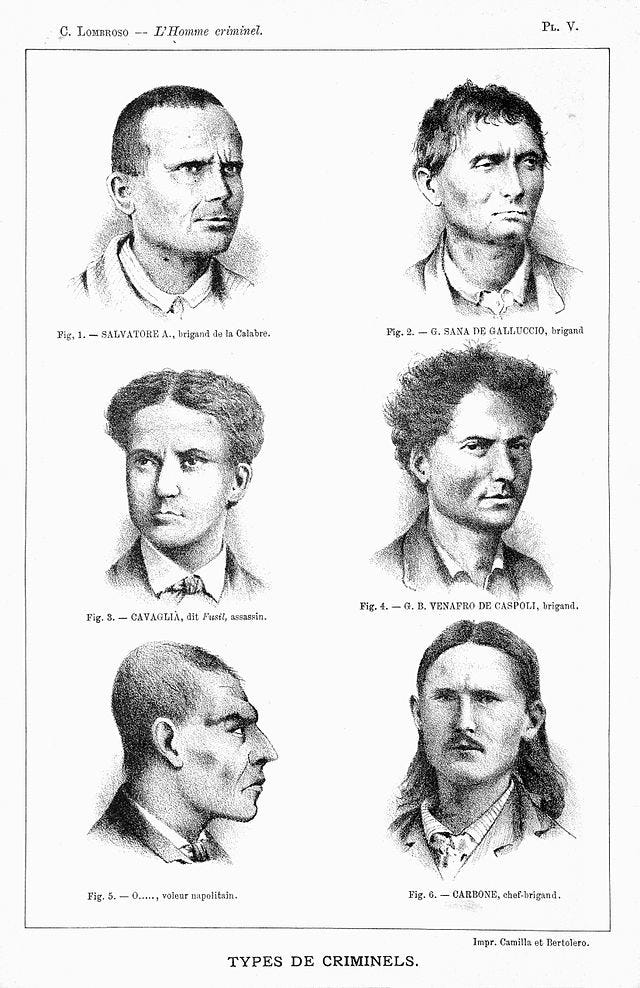

The physical signs of criminality came to be called stigmata. No coincidence – it was the same word that the witchfinders of previous centuries had used for the tattle-tale physical marks that identified a witch. Lombroso’s work is filled with lists like this:

“The eyes of murderers are cold, glassy, immovable, and bloodshot, the nose aquiline, and always voluminous, the hair curly, abundant, and black. Strong jaws, long ears, broad cheek-bones, scanty beard, strongly developed canines, thin lips [...] frequent contractions on one side of the face, which bare the canines in a kind of menacing grin, are other characteristics of the assassin.”

Furthermore:

“Thieves commonly show great mobility of the face and hands. Their eyes are small, shifty and obliquely placed [...] The eyebrows are bushy and close together, the nose twisted or flattened, beard scanty, hair not particularly abundant, forehead small and receding, and the ears standing out from the head. Projecting ears are common also to sexual offenders, who have glittering eyes, delicate physiognomy excepting the jaws, which are strongly developed, thick lips, swollen eyelids, abundant hair, and hoarse voices. They are often slight in build...”.”[ii]

Lombroso and his followers were not just early scientists. They were also early Italians. The two facts are not unconnected. In many ways, Italy was still a mishmash of badly-matching bits (some say it remains so – “thousands of countries” in which every mention of the word “State” is a pejorative one[iii]). Identity was hazy and negotiable. Italians needed some way to define themselves, or, more precisely, needed something to define themselves against.

Positivist criminology implied that a modern State could use modern science to identify its Enemies, outsiders, the so-called criminal classes. Italy needed to protect itself. The unproductive, the criminal, the anarchic – if the State were to succeed, they’d have to go. The fourth edition of Criminal Man included a long piece on criminals who wanted to overthrow the state. By the fifth, anarchists even had their own chapter.[iv]

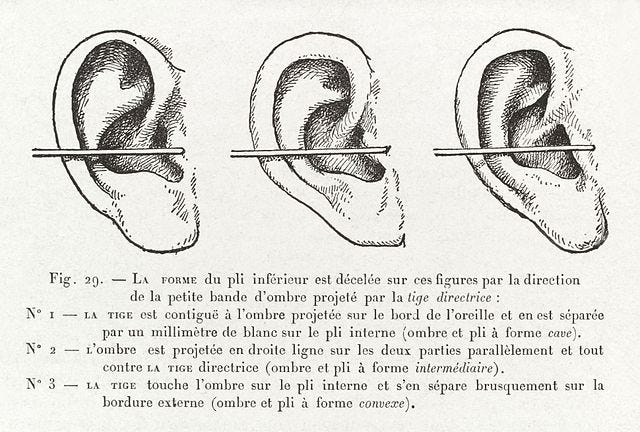

When it came to identifying these terrible threats, no stone was too small to turn. A researcher named Ottolenghi measured the space between the first and second toes. It was larger in criminals than civilians. Ears were interesting, too. Ears are as different as fingerprints. Criminals’ ears were even more different than that. The Italians produced a special taxonomy of types, arranged like a coffee chart at Starbucks – piccola, media, grande. Some criminals could even waggle their ears, and why not?

Indeed, many people’s favourite illustration from Criminal Man is the “criminal ear”. There are at least two important points. First, the ear lacks a lobe. Second, the helix, which for most people ends in the “crus of helix”, extends right across the ear canal. It’s handy to have Lombroso’s book with you if you happen to feel suspicious of the person standing next to you at the bus-stop.

The Italians understood that even ordinary civilians possessed stigmata. No one was without them. Having a few is not necessarily a bad thing. But criminals had them in combination. The person with several was a more likely criminal than the person with just a few: “We call a complete type one wherein exist four or more of the characteristics of degeneration; a half-type that which contains at least three of these; and no type a countenance possessing only one or two anomalies or none”.[v]

If you have fewer than five, don’t worry.

Not every stigma was visible. Some resembled medical or psychological symptoms. Certain criminals, for instance, had so little sense of pain that surgeons could operate without anaesthetic. One smiled with pleasure when he saw his own skin burning. Another sewed his lips and eyelids shut. Criminals like these would sometimes complain about minor ailments like colds, but suffer more serious ones without noticing.

Murderers blushed more readily than thieves. Female criminals might blush when asked about their menstrual periods, but not when asked about their crimes. They were sensitive to the weather and the seasons, and often quarrelled during spring.

Criminals’ handwriting was little better than hieroglyphics, their art looked like aborigine handicraft, and their slang resembled primitive languages. They were “savages” and they talked like them.[vi]

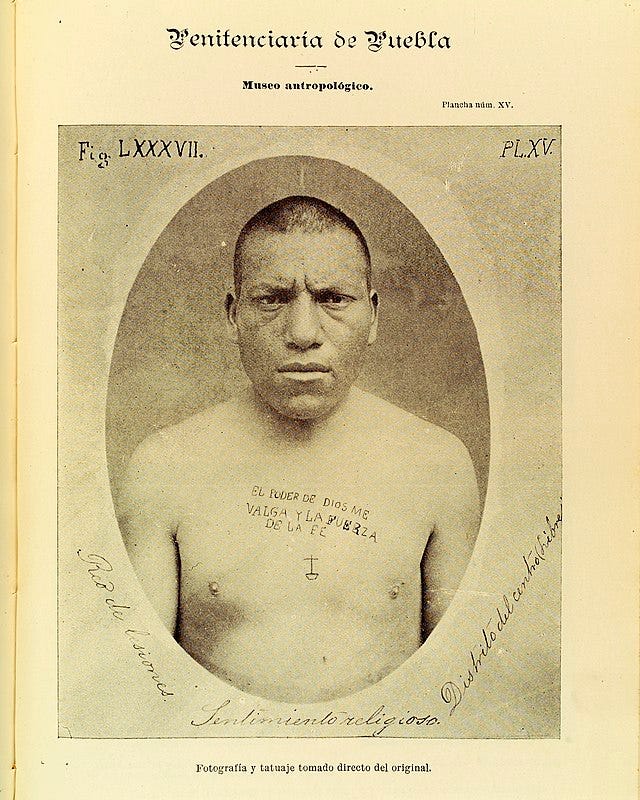

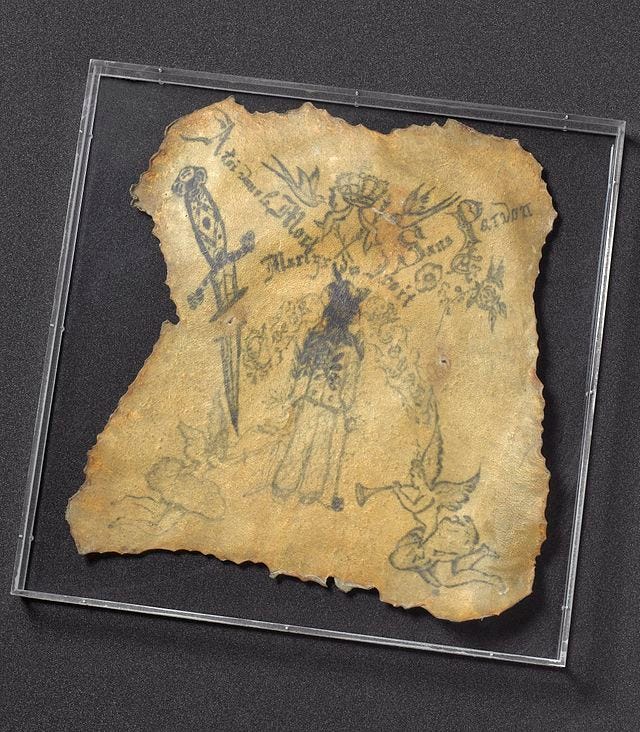

One stigma may surprise you. To the modern mind, tattoos are very different from, say, left handedness or bodily asymmetry. They are what biologists call “acquired characteristics”. A person decides to get a tattoo, in a way that they don’t decide to get a flat nose. But to Lombroso, tattoos were “an autobiography of a warped inheritance”.[vii] They indicated nothing so clearly as atavism. You could tell, because they became more common the further you travelled from Europe.

The idea has quite a pedigree. The Austrian architect, Alfred Loos, wrote that all ornamentation – whether on a building or a person - was degenerate and immoral.[viii] If a tattooed man died in freedom, he did so just years before he would have committed murder. In the 1990s, the English prison doctor Theodore Dalrymple wrote that, smoking aside, nothing was more closely associated with crime than tattoos[ix] (at least among whites). Indeed, he writes: ‘“A surprisingly large number of auto-tattooists choose for the exercise of their dermatological art the chief motto of the British service industries, namely fuck off”.

Alexandre Lacassagne studied 378 criminals, of whom 35 were tattooed “literally from head to foot”.[x]

Yes, that is a piece of tattooed human skin.

Many tattoos were obscene. The most common motif was the penis. Male criminals seemed peculiarly fond of decorating their genitals. Not even “savages” chose to do that. One man had the image of a nude woman tattooed over his penis. Yet another had a bouquet of flowers.[xi] Sex workers, meanwhile, often had the names of female lovers tattooed into their armpits (this observation raises more questions than it answers). Remember that homosexuality was a crime in Lombroso’s day. Hence he met numerous homosexuals in prison. They often decorated their thighs with pictures of wild pansies.

More visible were the hands and face. Lombroso records one prisoner with a dagger tattooed on his forehead and above it the slogan, Death to the Middle Classes.[xii] It’s hardly surprising that this man turned to crime. The tattoo can’t have helped very much in a job interview situation.

For the most part, women managed to resist tattoos, even if they did not always resist crime. Please belt a blue button:

So much for the male criminal. What did Lombroso have to say about the female? You’ll have to wait till next week to find out, Crime & Psychology fan!

All illustrations courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also so you can track down anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Ferguson, Niall: The War of the World, Penguin, London, 2009, op cit, (see last week’s newsletter) pxliv

[ii] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina: Criminal Man According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso, GP Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1911, pp244-5

[iii] Jones, Tobias: The Dark Heart of Italy, Faber & Faber, London, 2007, p12

[iv] Gibson, Mary & Hahn Rafter, Nicole: “Editors’ foreword” in Lombroso, Cesare: Criminal Man, trans. Mary Gibson & Nicole Hahn rafter, Duke University Press, Durham, 2006, p300

[v] Lombroso, Cesare, & Ferrero, William: “The criminal type in women & its atavistic origin” in Eugene McLaughlin, John Muncie & Gordon Hughes, (eds), Criminological Perspectives: Essential Readings, Second edition, The Open University: Sage, London 2003, pp47-51

[vi] Lombroso, Cesare, op cit, p78

[vii] Pick, Daniel, op cit, p117

[viii] Loos, Alfred, Ornament and Crime: Selected essays, translated Michael Mitchell, Ariadne Pr, 1997

[ix] Dalrymple, Theodore(2), “It Hurts, Therefore I Am”, City Journal, Autumn 1995, city-journal.org/html/5_4_oh_to_be.html Accessed 10th December, 2013

[x] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina, op cit, p47

[xi] Lombroso, Cesare, op cit, p59

[xii] Lombroso Ferrero, Gina, op cit, p47

Really interesting article. The connection between external and internal traits is also intriguing given that it suggests a monist interpretation of human nature. It also seems strongly biological and determinist which has implications about crime prevention, the identification of would be criminals, and what to do with both people who are likely to commit crimes and people who have committed crimes. The implications regarding the purpose of prison also seem less rehabilitative and more punitive because prisoners cannot change the shape of their ears, it seems by implication they cannot change the propensities of their behaviors.