YOU READ ‘CRIME & PSYCHOLOGY’ BECAUSE YOU’RE A HERO

Costumed crime-fighters; cinema; Carl Jung; Why heroes read ‘Crime & Psychology’

There he was punching Hitler in the face. He was just an ordinary man – a weakling, in fact - chosen from the common run of humankind to embody the best of our potential and stand up for all that was good and right. He knew evil when he saw it and he knew what to do about it. When the Führer left himself open to a right hook, he did not hesitate. He completely ignored the Nazi henchmen who were trying to shoot him[i]. Who could ask for a more sublime role model?

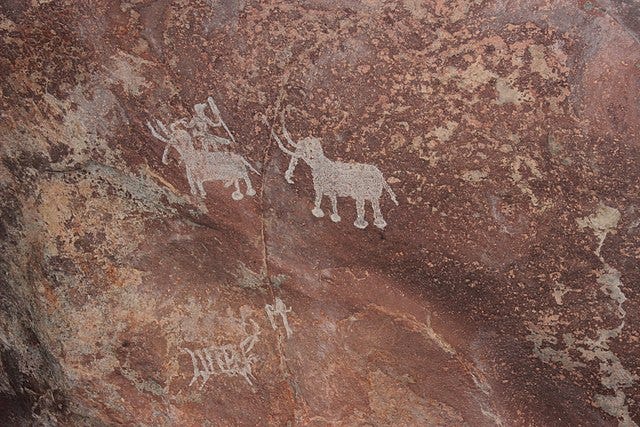

As any nerd will tell you, the hero in question is Captain America[ii]. And ‘hero’ really is the word. Cap and all his contemporaries from the Golden Age of Comics were twentieth-century versions of those classical heroes we can still read about, millennia after their adventures thrilled their first audience. Hero-worship antedates even them. Certain Stone Age cave paintings are thought to depict heroic individuals doing what heroic individuals have always done (courageous stick figures hunting great big bison, for instance). Like Hector, Perseus, Beowulf, and Robin Hood, Captain America possessed a quality, or set of qualities, that belong to myth. (I’d add Odysseus to this list but his wife, Penelope, stuck at home with her embroidery, has always struck me as far more heroic. Penelope didn’t even get the compensation of thinking, ‘Well, at least this’ll make a good story’.)

Myths are (usually) short stories designed to teach us bravery, determination, and compassion through a structure known as The Hero’s Journey. Here’s how it works:

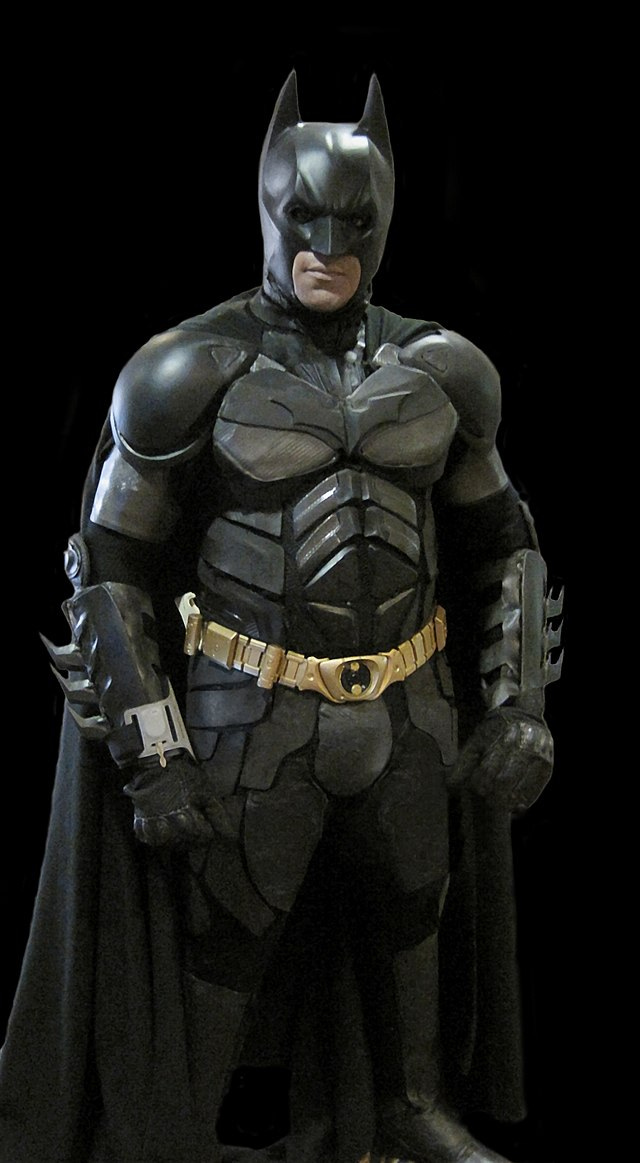

A more-or-less ordinary character lives under deeply imperfect conditions: Think of the young peasant Arthur before he pulled the sword from the stone or poor deluded Neo in The Matrix before he bumped into Laurence Fishburne. Think of weedy Steve Rogers before he took the super-soldier serum or Peter Parker before he went on that school trip to the radioactive-spider factory. (Think of Velma before she got her own series.) These circumstances represent the ‘status quo’. Now our character steps, or gets pulled, into a new world. He or she may be reluctant. Luke didn’t plan to become a Jedi; Frodo didn’t want to transport any Rings to Mordor. (Not every hero is reluctant, by the way – for every Peter Parker there’s a Diane Prince, Wonder Woman.) He or she endures tests and trials. Often they falter (this is vital. We’ll come back to it). The sharks attack and devour Santiago’s great fish in The Old Man & the Sea; Rocky Balboa realises he simply doesn’t possess the skills to defeat Apollo Creed. Red Sonja cannot lift the sword to fight off the marauders who kill her family. From these trials the Hero emerges stronger and tougher, able not only to smack Hitler in the chops but to fashion a brand new status quo. Simba, for instance, becomes the Lion King; Bruce Wayne adopts a cowl and cape and starts making Gotham City safe again. Arthur has a walloping great Round Table wheeled symbolically into his castle.

It's almost a cliché to point out that The Hero’s Journey is also the journey of Jesus Christ. Maybe that shows the power of religious narrative; maybe it’s the other way around. Let’s avoid that topic altogether and simply acknowledge the extraordinary power of such a story[iii].

The Ancient Greeks were just like the kids who laid down an eager dime for Captain America #1. They were just like the cinema audiences who queued endlessly for Star Wars forty years later. For that matter, they were just like you and me. In heroic fiction, we hope for and expect a glimpse of something more meaningful than our own limited, inchoate existence can give us; a world in which we might become more than we know ourselves to be. Heroes are not mirrors: they are lenses or perhaps figures in stained glass. They represent aspiration and potential. Their qualities are ones that we ourselves may not wholly lack but which we cannot begin to develop if we have no one to inspire us.

One of those qualities is simply this: the ability to pick ourselves up when we fall and carry on. Let’s think about that for a minute. The next paragraphs are about a real-life hero (mine, at any rate):

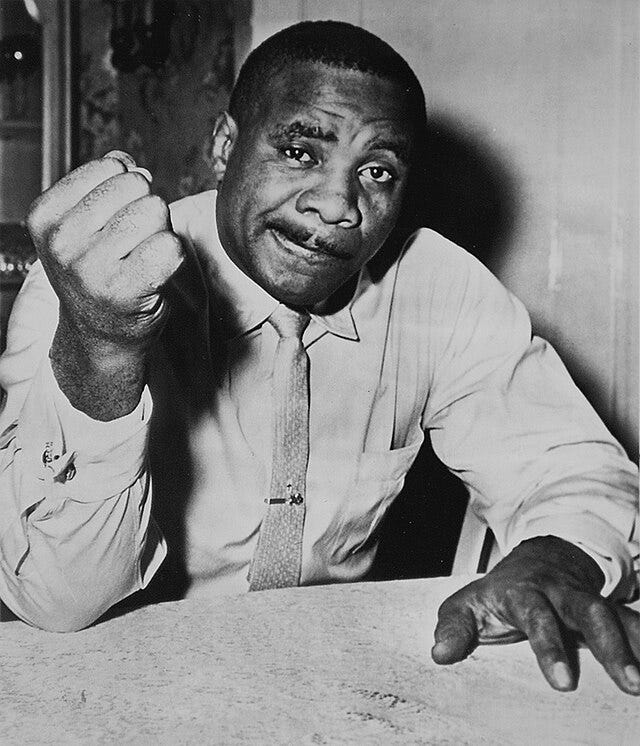

Muhammad Ali’s boxing career was split asymmetrically. In 1964, he outboxed a hulking, terrifying ex-con named Sonny Liston to win the world heavyweight title. He defended the title over and over again, beating the best athletes the sport had to offer, doing so with such grace and ease that some matches barely seemed competitive at all. That’s just how good he was. But this ‘prime Ali’ was hardly the beloved hero of later years. Indeed, the Ali of the sixties was frequently (there’s no other word for it) despised. Joining the Nation of Islam was never going to endear him to the regular sports fan. Neither was the occasional intemperate outburst. Worse, young Ali was dazzling – almost more divine than human. An ordinary person could relate to him as easily as to, say, Zeus.

Ali renounced his title because he refused to fight in Vietnam. When he returned, he’d been demoted. The Ali of the seventies was merely human. The new champion, Joe Frazier, beat him up and knocked him down. The man who’d once ‘handcuffed lightning and put thunder in jail’ seemed, suddenly, vulnerable. Yet he did what heroes do: he picked himself up and carried on. A few years later, this slower, less-dazzling, mortal man defeated a second terrifying hulk to take his title back. The terrifying hulk was named George Foreman, (and actually turned out to be a very nice chap). Along came the new status quo. Fight fans discovered they could relate to the older Ali more successfully than to the younger. They could see – or pretend they could see – just a little bit of Ali in themselves (maybe. It wasn’t impossible). By the late seventies, Ali may have been the best-loved person in the world. One BBC commentator remarked that, dropped anywhere on planet Earth, he could say, to the first person he met, two words guaranteed to make them smile. Those words were ‘Muhammad Ali’.

The structure of Ali’s Journey in the second phase of his career is virtually identical to the structure of every multiplex animation, at least since The Lion King. An underqualified misfit wants something implausible (a snail, for instance, wants to drive a racing car: Turbo, 2013). Someone or something scary stands in the way. Our underqualified misfit tries, fails, wanders off into a darkness that is either literal or metaphorical. (Probably they run into a loveable but goofy sidekick who happens to have nothing better to do than hang out for the next 45 minutes.) Our misfit studies, trains, returns. Overcomes. Triumphs. Under the new status quo they are a misfit no longer. Everyone loves them. Anywhere on planet Earth, you could say, to the first person you met, one word guaranteed to make them smile. That word would be ‘Simba’.

But recently – have you noticed? - the vital pick-yourself-up-and-carry-on part of the story has gone AWOL. It’s gone MIA. A new character has popped into our postmodern fictional alphabet. She’s called the Girlboss. The word comes from an autobiographical book by Sophia Amoruso, but its meaning has changed since publication date in 2014. It refers now to a female protagonist who takes the place of the traditional ‘hero’, but who does not quite follow The Hero’s Journey.

Take Carol Danvers from the Captain Marvel films. She is the most boring character in cinema history. There is no Journey for her to go on because she’s already there from the first reel. She starts at her destination. She bears comparison with Ali in the first part of his career - mega-powered, invincibly overequipped, she never falls down, so she never has to pick herself up again. Cinephiles do not love her. (It’s traditional among fans of the Marvel Comics Universe to contrast Carol Danvers with Tony Stark, who is a much better-written character. There’s an example here. Everyone prefers to Vincible Iron Man to the Invincible Captain Marvel.)

Luke Skywalker’s Jedi abilities came at the cost of time, effort, pain, and the temptation to give up altogether. You and I, watching Luke’s Journey, can empathise. We know how he feels. We know that we’d be tempted to go back home, too, if we were him. Luke’s girlboss replacement, Rey, never was tempted. Why?: because she too began her Journey at the destination. And if you’ve missed the controversy that has caused…well, good for you. I wish I had. You can read more about it here.

Invincible characters don’t need to pick themselves up and carry on. Yet it is precisely the ability to do so that inspires us, the viewer, to try to do more than we think we can. Only in such a way can we hope to reach, or at least approach, our own potential.

In the paragraph above, I compared two female protagonists with the males they replaced. What a pity that the hero-issue has become entangled with the gender-issue. If I were one of those playful postmodern writers, I’d probably remark that the elephant in the room is actually a red herring. An otherwise-welcome influx of women into the entertainment industry simply came along at almost the same moment the Hero vanished. In fact, we are dealing here with a gender-free human universal. It’s easy to identify with Tony Stark, whatever your own gender may be. Equally, Carol Danvers can hardly fail to irritate the hell out of you.

Lead characters are unpopular not when they are female (as some directors have defensively claimed) but when they are boring and badly written and we can’t relate to them. There are plenty of heroic female characters in cinema whom even the most hermetic incel can appreciate, and often does. Sigourney Weaver in Alien and Linda Hamilton in Terminator are popular examples.

Cinema has seen repeated attempts by postmodern production teams to mock, malign, or even replace Heroes. Take Mad Max: he didn’t even appear in the last Mad Max film. It bombed. Luke Skywalker turned into a hermit who had green milk in his beard. Fans created a special Facebook group to defend him. To belittle heroes has become a feature of our time. Such small-minded cynicism brings to mind adolescents making scatological jokes about their childhood toys or television programmes. They do it for the purpose of letting everyone know how very grown-up they are now. In truth it lets them know exactly the opposite.

It is easier, as everyone knows, to destroy than to create.

The kind of petty-mindedness I refer to never comes out into the open and shows us what it is. The petty-minded like to use terms like ‘acceptance’ and ‘compassion’ and similar buzz-words. As you know, the greatest trick the devil ever pulled was making us believe he does not exist. The devil preaches acceptance of everything because once you accept everything there’s no need to strive for anything better. The mediocre – the acceptable – is always and forever the enemy of the great.

Popular Psychology is a big factor here. ‘You are good enough as you are’ - that’s the mantra. Indeed, it’s all about you: ‘You deserve to feel good about yourself. Be yourself. Love yourself. Accept yourself.’ All well meant, of course, of course. No one intended the mantra to be the destructive force it has become. The devil makes us believe he does not exist.

Once I decide I am good enough as I am, there’s little point trying to improve. Or, rather, my sole remaining task is to convince everyone else to agree with me. One useful strategy is to bring them down to my own level. Then we can all be good enough as we are.

The self-esteem movement has a great deal to answer for. I wrote about it in a previous newsletter, which you can read by following this link.

Here is the psychotherapist Nathaniel Branden: ‘I cannot think of a single psychological problem - from anxiety and depression, to underachievement at school or at work, to fear of intimacy, happiness or success, to alcohol or drug abuse, to spouse battering or child molestation […] that is not traceable, at least in part, to the problem of deficient self-esteem’.[iv]

And then there was California’s Task Force for Self Esteem and Personal Responsibility. The idea was to prevent crime, violence, substance abuse, teen pregnancy, (and just about every other problem you could think of,) simply by raising everyone’s self-esteem. It was a dreadful idea. Why? Here is the world expert, Roy Baumeister: ‘Violent acts follow from high self-esteem. This is true across a broad spectrum of violence, from playground bullying to national tyranny, from domestic abuse to genocide…’[v]

It doesn’t get much starker than that.

‘Feeling good about oneself’ is fine as far as it goes. But too easily it becomes complacency, pettiness, envy, and all those other emotions that Heroes never feel, or which they choose to strive against.

Instead of trying to emulate our heroes, today we are forcing our heroes to emulate us. As the character Syndrome remarks in the superhero cartoon The Incredibles, if everyone is super, no one is super.

Friedrich Nietzsche, the German philosopher, famously claimed that ‘God is dead’. We human beings needed to create a new morality. One step is to discover role models. ‘Who will wipe this blood off us?’ Nietzsche asked. His answer was the Ubermensch. It may be no coincidence that the word translates into English as Superman.

As any nerd will tell you, Superman – the comics character – is Good. No humdrum human, he: Superman does good for no other reason than that it is, well, Good. He needs nothing else. And that is something we should aspire to.

The famous psychologist, Carl Jung, feared living in a world that lacked myths, or Heroes. In fact, he feared living in the very world you and I are forced to slump and trudge through every day. And yet he spied dangers even in heroism. A person who tries to be as good as Superman may become blinded by their own Shadow (Jung liked these capital letters – they were part of his own psychoanalytic mythos, which we shan’t get into here). The closer we come to the light, Jung reasoned, the darker our Shadow grows. We may find ourselves blinded by hubris and self-righteousness.

Jung claimed there were two routes to goodness. The first is simple naivity. One can exist on life’s pleasant surface, never thinking about or suspecting the dark caves underneath or the rough beasts that slouch towards Bethlehem to be born. The second route is to venture beneath the surface and learn the awful truths of existence. One must learn about evil because to do so is itself a positive good. Only a person who understands Evil has the opportunity to be really and truly Good. Batman refuses to murder his enemies, no matter how appalling they are or how badly he is tempted. That is because Bruce Wayne learnt all about evil. So did Frodo; so did Luke Skywalker (‘I will never turn to the dark side. I am a Jedi like my father before me.’) Corny as it is to say so, darkness is where heroes shine brightest.

To encounter evil is to learn to negotiate the darkness. That’s why you read true crime. That’s why you keep up with the news, however awful. That’s why you read the Crime & Psychology Substack, you hero, you. Like Captain American punching Hitler in the face, you’ve learnt to recognise evil when you see it.

Here is a link to a related newsletter from Green Tea & Post-It Notes. It’s on a very similar topic.

Bang a bright blue button and support this super Substack! Even better, buy me a coffee!

All images courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided mostly out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything you find especially interesting.

[i] Robb, Brian J : A Brief History of Superheroes – From Superman to the Avengers, the evolution of comic book legends, Running Press, London, 2014, p 73

[ii] One of Cap’s creators was a bit of a hero, too. American Nazis got more than a little annoyed with this representation of Hitler and stormed into the comic-book offices. Former street-tough, Jack Kirby, the man with the pencils, got stuck in. Soon thereafter he went off to fight in Europe.

[iii] The Jungian psychologist, Maureen Murdock, developed what she called The Heroine’s Journey. It shed some light on the different routes taken by male and female protagonists. Interestingly, the Heroine often has to renounce characteristics or qualities that may appear overtly feminine. In other words, her Journey may involve taking on male characteristics. This interesting idea deserves 2000 words of its own. For that reason, I’m not going into more detail right now. If you like, you can perfectly well read ‘Hero or Heroine’ for ‘Hero’.

[iv] Branden, N: The Psychology of Self-Esteem, Nash Publishing, New York, 1969, p5

[v] Baumeister, Roy: Evil – Inside human violence & cruelty, Henry Holt & Co, New York, 2001, p25

Thanks for this thoughtful article which connects up a bit with what ive been writing about our cultural superheroes. Elvis partly modelled himself on Captain Marvel Jr. Im also not a huge fan of the self esteem movement. But sometimes the drive to be a hero is trauma based and hides an extreme lack of self esteem - despite what it looks like. Some of our greatest superheroes have broken down because of this thorn in their side.

Really interesting and introspective letter this week. I found this piece provocative that it's making me think about heroes and their roles. I think that you are mostly right about the new kind of heroes. I do think there is a danger in heroes/role models because they suggest archetypes and usually hide the person's flaws. One of the interesting things about Luke and other such fictional heroes is that they failed, that they have bad impulses, perhaps, that they considered being evil.

I tend to argue that we should have more accurate representations of people and recognize that no one is all "good" or all "bad." Thus, when thinking about certain heroes we should also emphasize their flaws. It seems that heroes that start at the destination have even fewer flaws.

More profoundly, I suppose, I am a little worried about role models bc they imply that there is a stationary set definition of what is good rather than an evolving one. When I taught I did not want to be a model of what students should aspire to be. Rather, I wanted to be the flawed individual that I am. An individual who hopefully makes some good choices and has some good traits, and an individual who makes mistakes, does some tasks poorly, and that is surely wrong about a lot of stuff he thinks he is right about. However, I suspect you could think of heroes as tools and as the zeitgeist changes society creates new one that reflect the new views.

Your discussion of Jung made me think that these myths may be necessary. If memory serves right Nietzsche also argues that they can be useful for society. I think myths can be healthy and important... I ask myself whether there is a difference between myths that are taken to be real or myths that are valued but that they are recognized as myths.