GROUP CONFLICT & ETHNOCENTRICISM

Conformity; football hooliganism; ethnocentricism; Nazism; social identity; self-esteem

Israel or Palestine; terrorist or civilian; authoritarian or democrat; criminal or victim; liberal or conservative; Russian or Ukrainian; anywhere or somewhere; Brexiteer or remainer; oppressed or oppressor… The news is all about groups. The news is all bad. And that word ‘news’ is wrong. There’s nothing new about it. It’s all Psychology and we all need to know all about it. They should be teaching this in the schools.

Although it’s long enough to split across two of our Wednesday newsletters, this will be a relatively short guide to what any psychologist could tell you is a giant subject. You could write a book. You could write a shelf of books. You could probably even write a library. It’s a grim subject: ‘devastating’ would perhaps not be too big a word. And so we shall start with an engaging example.

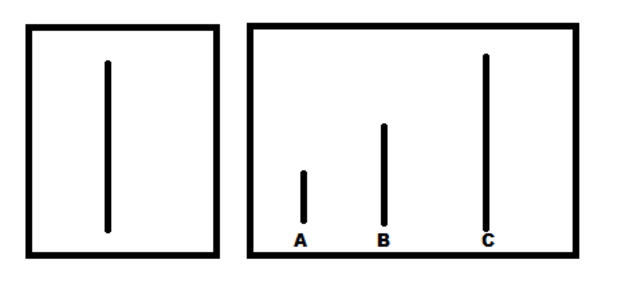

Take a look at the line on the left. Which of the lines on the right matches it? Not too difficult a question. It’s C, right? (No trick. It really is C.)

Here is the point: everyone who can see the lines knows the answer. They can be in no doubt. And yet, under certain conditions, about one-third of the time, people get it wrong. At least, they say they do.

The line-length experiment tells us that when we put a perfectly-ordinary citizen into a group with six other perfectly-ordinary citizens, about one-third (32%) of the time, they are willing to deny the clear, unambiguous evidence of their own senses. When those other perfectly-ordinary citizens give an answer that is clearly wrong, B, they far too often just cave in to group pressure.[i]

Let’s restate that important discovery: One-third of the time, people deny what they know to be the truth, in response to a group of others who say something they know to be false.

‘A member of a tribe of cannibals accepts cannibalism as altogether right and proper.’ So said the social psychologist, Solomon Asch. What he meant should be clear: put a perfectly-ordinary citizen into a group with six cannibals, and you can bet, 32% of the time, they’ll be asking you to fry the toes extra-crispy. Extra toenails, please.

Why, Solomon Asch asked, did those perfectly-ordinary citizens cave in? Every reply he got to his question was a negative reply. They did not want to disrupt his experiment, they said. They did not want to break ranks, or look foolish in front of the other group members. Some even denied that they’d done what they’d done. They insisted that they’d given only what they believed to be the correct answers, thus compounding the error.

I once replicated the line-length experiment myself, informally, in an undergraduate class. It worked pretty well, except in the case of one student, who said that it was ‘impossible to know’ which of the lines matched. No matter how I asked the question, he insisted that ‘no one could possibly tell’. Except that they could. They very clearly could.

This is about to get dark. ‘Those who can make you believe absurdities,’ said Voltaire, ‘can make you commit atrocities’. (In actual point of fact, Voltair did not quite say that, but who am I to argue? I don’t want to contradict the group…)

If a group can make people deny what their own eyes are telling them- even when it doesn’t matter, even when the stakes could hardly be lower – imagine what it could do if membership was a major part of a person’s identity, or the only place they felt any sense of self-worth. Imagine what it could make a perfectly-ordinary citizen do, if it demanded violence. Imagine what a criminal group could make them do.

In the 1970s, football hooliganism was making headlines in all the British newspapers. It seemed that every match-day was also fight-day, fans wading knee-deep through blood and broken teeth just to get to the stadium. What was going on? Researchers discovered exactly what you may be starting to suspect by now. It was wrong to speak of individual hooligans. You could only speak of groups of hooligans.

The group (the football-hooligan group) was more important to its individual members than any individual member was to the group. It was therefore in a position to make demands: demands for aggression and violence.[ii] Whatever wrong the individual hooligans did, you could blame pressure from the group. Like Asch’s experimental participants, they did not want to break ranks, or look weak in front of the other group members. To lose face in such a way would be to lose other things, too: friends; support; a sense of self-esteem; something to do on a Saturday afternoon. Either make others suffer, or suffer yourself.

Just as I was writing this piece, I came across an article by the novelist, Martin Amis, explaining his own experience of attending a football match:

‘[The crowd] is asking something of you: namely the surrender of your identity. And it will not be opposed – it cannot be opposed. The crowd is a wraparound millipede, and it is thrillingly combustible. With relief, with humiliation, with terror, you lose yourself in the body heat of innumerable torched armpits, in the ear-hurting roars and that incensed whistling like a billion babies joined in one desperate scream.’

Gotta love that ‘wraparound millipede’!

Groups: more powerful than we think; more dangerous than we imagine.

Let’s explain Social Identity Theory (SIT). The idea is that, instead of having just one identity, you and I actually have two. Psychologists call them the personal and the social. Personal identities are exactly what you might expect. They derive from our close relationships –friends, spouses, extended family – and the character traits we happen to have, or think we have – optimism, reliability, a sarcastic sense of humour, for example. In a post about groups, we don’t need to go into any depth about this.[1]

Social identities, though – they are the turbulent, trouble-causing, dark heart of it all. They entrain conformity, obedience, rules, discrimination… It’s enough to make anyone shudder.

People want to feel good about themselves. In fact, our postmodern culture soaks us daily with messages that have no other content: body positivity; self-compassion; spiritual wellness; self-esteem. We can approach that all-important feel-good sensation by sprucing up either half of our identity – personal or social.

According to Social Identity theorists, people are continually categorising themselves as they evaluate and re-evaluate their in-groups and out-groups,[iii] trying to negotiate the snakes and ladders of the social world in order to end up feeling as good as possible.

Think about sports fans. How do they feel when their team wins? For one thing, they feel what Social Identity Theory says they want to feel. They feel immediately, automatically good about themselves. So good, in fact, they want everyone to know all about it. They leap up and down and shout. ‘We won! We’re the best!’ And yet ‘we’ had nothing to do with it. The team won: while their self-esteem was busy rocketing through the roof, the actual sports fan was just sitting on the sofa.

If the team loses, what then? Well, that makes sports fans feel kind of bad, doesn’t it? It’s a zero-sum game, after all. In sports, every good feeling comes at the expense of someone else’s bad one. One strategy is to shrug off the blame. It was the team who lost, after all. Them. This time, sports fans are willing to acknowledge that they were in fact minding our own business on the sofa at the time.

Regrettably, as you know, certain people are wired such that making other people feel bad is enough to make them feel good. We’ve all encountered the hair-splitting bureaucrat, the intellectual snob, the self-appointed arbiter of taste – not to mention the sadist, the amateur torturer, the family tyrant.

SIT is founded in well-known research by the psychologist Henri Tajfel. When it came to group behaviour, Tajfel certainly knew what he was talking about. His entire close family was exterminated by the Nazis. He spent six years after the Second World War helping repatriate and resettle those poor souls who’d been displaced for no better cause than membership in the wrong group. One of the most robust phenomena in all of social psychology is his discovery, years later, that merely classifying or categorising someone can be enough to produce such hostile side-effects as discrimination and prejudice.

That’s worth stressing that. Merely classifying someone is enough. ‘Social categorisation’, psychologists call it. It lies behind the feeling we all experience from time to time - that Our group is different from Their group. Our group is composed of people who are unanimously original, interesting, good, and respectable: Theirs, meanwhile, is composed of individuals who are all the same; far less interesting and good than ours. (I can assure you, social psychologists are an entirely different breed from cognitive or forensic psychologists like my friends and me…)

Tajfel referred to ‘minimal groups’. His research plan had been to find the minimal conditions under which social groups would start to act in an ethnocentric manner. He began his programme by classifying people (schoolboys in Bristol, England, in fact) into groups based on the most minimal criteria, such as whether they over- or underestimated the number of dots on a slide, or preferred the abstract paintings of Klee or Kandinsky. The idea was to keep introducing new layers of complexity until such time as ethnocentricism appeared. But it took nothing. The dot task was enough: the abstract-painting task was enough. Even a straightforward lottery system or the toss of a coin was enough – the Heads were just as prejudiced against the Tails as the Klees were against the Kandinskys.

The implications seem to verge on the ludicrous: ‘A minimal group categorization could consist of wearing either a yellow or green hat. Without any other experiences with in-group or out-group apart from the color of their hats, group members should favor the in-group and allocate more resources to individuals with same-colored hats, according to the minimal group paradigm’.[iv] That’s right – hats. Hats are enough to make us discriminate against others. One eminent social psychologist calls this phenomenon ‘truly Kafkaesque’.[v]

I used the word ludicrous, above. Another word for ludicrous is laughable, and laughing is a behaviour restricted to people who have a sense of the absurd. We all know how dangerous people are who do not. Their inability to recognise what is absurd can lead them to do things that are precisely that.

Uncertainty, ambiguous surroundings, threat, novelty –all have their effect. They cause our identity to glide and slide. When that happens, we look for a crutch to lean on. Group membership can work. We grab for it to keep us upright in a tilting world. The jargon term here is ‘salience’: as in ‘ambiguity increases the salience of group membership’ or ‘native speakers resort to in-group slang when membership becomes particularly salient’.

If group membership gives us a crutch to lean on, it also does something even better (or worse). It gives us someone to pick on, someone to take it out on, someone whose inferiority makes Us feel better about Ourselves.

Nothing makes groups more salient than competition. Pit two groups against each other – make them compete for land, water, prestige, even just some meaningless trophy - and there’s no avoiding the effects of SIT. The happy social psychologist can simply sit back and take notes while cloudbursts of data thunder down.

Here’s an exercise that you can carry out at home: Open up your news app of preference. Try to find an item there that vividly illustrates the effects of group membership. Or – wait - here’s a better exercise: try to find one that doesn’t.

And here is a link to Part 2 of this article.

All pictures courtesy of Wiki Commons.

References supplied partly out of academic habit; partly so that you can read more about anything you find particularly interesting.

[1] There is a minor distinction to be made between Social Identity Theory and Self-Categorisation Theory, but it’s one we can ignore for present purposes.

[i] Asch, SE: ‘Opinions & social pressures’, Scientific American, vol 193, 1955, pp31-55

[ii] Marsh, P: The Rules of Disorder, London, 1978, Routledge & Kegan Paul

[iii] Trepte, Sabine & Laura S Loy: ‘Social identity theory and self‐categorization theory’, The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects, 2017, pp.1-13.

[iv] Trepte, Sabine & Laura S Loy, op cit, p2

[v] Brown, Roger: Social Psychology – The second edition, The Free Press, New York,1986, p544