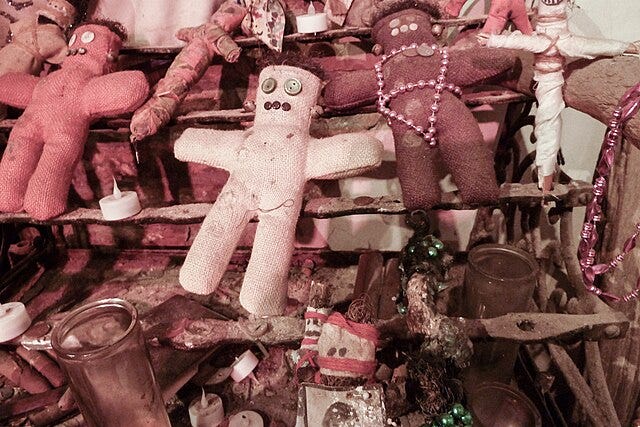

VOODOO DEATH AND PSYCHIC HOMICIDE Part 2

In which we look at the phenomenon of Psychic Homicide itself and explain why you shouldn't sleep in a room with an electric fan. Plenty about homicidal mania and placebos.

In last week’s nifty newsletter, we discussed various voodoo spells. We saw that there are good reasons, based in cognitive psychology, for some of them to work, or seem to. We can explain what Albert Einstein called ‘spooky action at a distance’ without leaning too heavily on the ‘spooky’ aspect of things. We also encountered the concept of Sudden Unexpected Death (SUD), and saw that, while it appears to be a real medical phenomenon, it doesn’t quite fit our idea of ‘Voodoo Death’. The researcher, Walter Cannon, explained Voodoo Death in psychological terms. He said that ‘it is the victim’s mental state that makes sorcery effective, not bone-pointing or effigy-burning’.[i]

That is where we left off last time. Let’s see what else we can learn…

Remember how we started this newsletter – with the tremendous power of thought. If the mind is really what creates our world, as cognitive psychologists suspect, it’s hardly far-fetched to think that the mind can end it, too. That explains why certain psychological syndromes appear only within the specific cultures in which they are accepted, and not elsewhere. There are various examples. Amok, for instance, is a homicidal mania that seems to appear only in Malaysia. Murder and cannibalism are sometimes explained as ‘going windigo’ among certain peoples in North America. Southeast Asia is the world’s only locus for a very specific brand of anxiety called koro.[ii]

There is even a regional Korean phenomenon known as fan death. It seems to occur nowhere else whatever. It is the belief that it can be fatal to run an electric fan in a room with the windows closed. One government department has claimed that seven to ten Koreans die every year as a result of fan death. Korea’s champion electric-fan manufacturer, Shinil Industrial Co., issues warning along with their potentially-deadly product. Keep it pointed away from you at night![iii]

Indeed, even such a phenomenon as romantic love – which seems, to most of us, pretty much part of the human genotype’s basic carry-on luggage – appears only in certain cultures. If you are born into a culture in which romance is not, so to speak, a thing, it seems you don’t get to fall in love.

The power of the mind: People have sometimes been known to will themselves either to die or to live. Examples are not notably lacking, but a single one may do. One researcher mentions an old man who ‘seemed to be dying, but for whom no medical problems could be found. A female shaman had persuaded the man’s wife to cut some of his hair and give it to her, whereupon she used the hair to work a spell to hex him. The doctor then devised a ceremony in which he also cut some of the man’s hair and burnt it to ash and declared that he had thereby destroyed the hex. The patient then recovered’.[iv]

All of this links neatly to what has been called the ‘given up/giving up’ phenomenon. The victim of a hex often simply refuses either to eat or drink. They see no point. This seems like a special example of what psychologists call ‘learned helplessness’, a phenomenon which is sometimes used as a model for clinical depression: the patient has internalised the idea that there is simply nothing they can do to escape the dark situation in which they find themselves trapped. They simply abandon hope. This is the giving up part. Alternatively - and perhaps even more tragically - their family refuse either to feed them or give them water – a behaviour sometimes called ‘senilicide’. This is the given up part. It may be present in a majority of cases of ‘voodoo death’.

‘[I]n many traditions the victim of voodoo death has, by definition, crossed into the realm of the spirits, and thus become an actual threat that must be removed. […] Weakened by the long ordeal, the victim of sorcery receives no relief even from close relatives’.[v] (Well, we’d all enjoy some relief from close relatives from time to time.)

A hex that can have an effect as powerful as that is definitely one to be reckoned with, supernatural or otherwise.

Naturally, getting cursed causes stress. It would, wouldn’t it? Even non-believers like you and me might feel pretty stressed if a voodoo doctor laid a curse on us. If nothing else, I dare say we’d be upset to learn that he disliked us quite so much. We’d become anxious. Anxiety – a psychological state which we usually associate with the mind - can create physiological effects in the body. Stress appears to lead to a weakening of the body’s defences (note, for example, high mortality rates among people who have recently been widowed).

Stress can certainly be implicated in cardiovascular disease and even SUD, which we addressed earlier. It is a striking discovery that victims sometimes die as a direct result of a physical assault, even if they sustain no actual injuries. Autopsies show damage to the heart, which seems to be a result of stress. It’s interesting to ask how the police should treat such cases – as assult or murder?[vi]

There has been some debate about whether ‘voodoo death’ is a physiological or a psychological phenomenon. You’ll have noticed that, throughout this newsletter, I’ve been arguing that the whole debate is a bit artificial, because our minds and the physical worlds we inhabit are less separable than we tend to think. What we see when we look around us is partly a reflection of what is really out there in the world, but partly also a reflection of our own cognitive processes. It’s the same with what we feel or think. Stress (a psychological phenomenon) has effects on the body, as we’ve seen; equally, a new, unexplained pain in the body can cause the psychological phenomenon we call worry.

Most psychologists would argue that all of psychology is in some sense rooted in the physical stuff of which we and the rest of the universe are made. That is why such important ‘psychologists’ as Wilhelm Wundt, Ivan Pavlov, and even Walter Cannon himself were in fact trained as physiologists.

At this point, it’s worth turning our attention to nervous systems. The so-called autonomic nervous system (or ANS) is a mostly unconscious one that governs smooth muscles, glands, and internal organs. It regulates such bodily functions as heart rate, digestive processes, and sexual arousal. Hans Eysenck, when he put together his theory of Crime and Personality, was particularly interested in the role of the ANS. You can read more about his theory here.

As in any complicated bureaucracy, there are internal subdivisions. The ANS is split into three parts: the sympathetic, parasympathetic, and enteric nervous systems. The sympathetic nervous system is involved in what psychologists sometimes euphonically call the ‘fight-or-flight’ response, by which we mean the body preparing itself for survival – either battling it out with some enemy or predator, or choosing to run for one’s life. The parasympathetic system is involved in the equally-euphonic ‘rest-and-digest’ response, which probably doesn’t require any elaboration from me.

Walter Cannon, along with his PhD student, Philip Bard, liked to stress the role of the material stuff of the brain in producing intangibles such as emotion. In one particularly unpleasant piece of research, they cut the cortex (that is, the outer layer, or ‘grey matter’ of the brain) off cats. Such ‘decorticated’ cats became easily, and randomly, angry. They displayed what Cannon called ‘sham rage’, directed at more or less anything and everything (who can blame them?)

Cannon’s cats sometimes died after intense explosions of rage. Their deaths, he thought, were reminiscent of voodoo death in human beings. He pointed to over-stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system.[vii] Prolonged over-activity there led to shock and shock led, quickly or otherwise, to death.

Other physiologists disagreed. Laboratory rats sometimes die when they are placed in threatening situations which they simply cannot escape. It is as if they give up in despair. This is sometimes called ‘vagal death’. Despair does seem to be the key: rats who have been placed multiple times in similar situations, but allowed to escape, are far less prone to vagal death. Physiologists blamed overstimulation of the parasympathetic nervous system.

Putting these two sets of results together, we get a clearer picture of a ‘generalized autonomic storm’[viii] which may overwhelm both sympathetic and parasympathic systems and sometimes lead to so-called ‘voodoo death’.

Let’s consider one final case in which psychology and physiology mingle. Voodoo – despite the notoriety of its doctors and curses – is based ultimately on healing. Here is one voodoo priestess, called Rev Lady Bishop:

‘The primary purpose of voodoo is healing with herbs, prayers, rituals, and spiritual intercession. Too many people correlate voodoo with pins and needles stuck in dolls to create pain and suffering. That is witchcraft, not voodoo. But it can also be an extension of voodoo in the hands of a person who was evil to begin with’.[ix]

Some researchers have likened phenomena in voodoo to phenomena in medicine, in particular faith-healing and the placebo effect.[x] We know the effect of placebos – that is, medically inert substances that seem nevertheless to be effective in treating illness. Again, as far as we can distinguish the two, they work for reasons both physiological and psychological. You will not be surprised to learn that the expectations of both the therapist and the patient affect the usefulness of a placebo. So, too, does what psychologists call ‘conditioning’ – by which we mean whether or not the patient has previous experience of similar interventions, and whether or not they seemed to work. Seemingly-irrelevant factors like the size of the pill, its form, and even its colour have an effect. Two totally-inert pills are better than one, and totally-inert capsules work better than totally-inert tablets. Lively colours like yellow make for the most effective anti-depressants. ‘The placebo is effective because of the patient’s beliefs’ - so writes one expert – ‘[…] Cognitive factors include expectation, faith, and enthusiasm’[xi].

You may be suspecting that the placebo could have an ugly twin. If so, you are right: there is also the ‘nocebo’, the name of which translates as ‘I will harm’. Here we have another example of the mind actively creating the outside world. In this example, the mind makes it a threatening place. (Something similar is commonly seen in patients who have depression. If happiness fits us with rose-tinted spectacles, depression does the same with spectacles that have more of a dirty-grey effect.)

If placebos work best when a smiling doctor confidently hands the patient two big yellow tablets and assures them they will soon be on top of the world, feeling much better, well, it’s easy to see how the nocebo effect might work just as well – or just as badly. Have a grimacing sorcerer hand the patient a single small brown capsule and assure them they will soon be at the bottom of the world, feeling much worse… Voodoo curses and the like may simply represent a particularly virulent version of the nocebo effect.[xii]

By this point, we can start to see voodoo death for what it is: a dramatic phenomenon that appears supernatural – scary, even – but which Psychology can finally explain. Here is one excellent summary: ‘The psychological deterioration of an individual afflicted by a sorcerer’s curse may be imagined. The victim has shared an uncompromised belief, engendered since childhood, that illness or death will befall anyone who transgresses the societal code of behavior; and his or her acceptance of the supernatural power behind the instigator of the curse is equally fixed and unshakeable. He or she is doomed to die by a malevolent curse in which everyone involved deeply believes’.[xiii] And, as we saw earlier, believing is seeing. Believing, in fact, can actually be everything.

Be brilliant and bop a blue button. It helps keep this newsletter going!

On this subject, if you happen to be in Portland, Oregon, I have to recommend Voodoo Doughnut.

No, they’re not paying me or anything. I just love their doughnuts!

Marie Laveau and Voodoo Museum pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also to allow you to chase up anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Walter Cannon, Marvin Harris, both quoted in Bodin, Ron, op cit, p39

[ii] Davis & DeSilva, op cit, p37

[iii] Herskovitz, Jon: ‘Electric fans and South Koreans – A deadly mix?’ Reuters, August 9, 2007, Available at Electric fans and South Koreans: a deadly mix? | Reuters

[iv] Lester, David, op cit, pp4-5

[v] HD Eastwell, quoted in Davis & DeSilva, op cit p39

[vi] Samuels, Martin A, op cit, pS13

[vii] McCarthy, R: ‘The fight-or-flight response – A cornerstone of stress research, Stress: Concepts, Cognitiuon, Emotion, & Behavior, Handbook of Stress Series vol 1, 2016, pp33-37

[viii] Samuels, Martin A, op cit, pS8

[ix] Quoted in Bodin, Ron, op cit, p72.

[x] Zusne L & Jones WH: Anomalistic Psychology – A study of magical thinking, Second Edition, Psychology Press, London, 2014, p57

[xi] Solomon, Seymour: ‘A review of mechanisms of responses to pain therapy – Why voodoo works’, Headache, 42, 2002, p655

[xii] French, Christopher C: ‘The placebo effect’, Parapsychology, Routledge, London, 2001

[xiii] Davis & DeSilva, op cit, p46