THE INCREDIBLE AND SAD TALE OF GRUMPY ALPHONSE AND HIS DOOMED SYSTEM FOR MEASURING CRIMINALS

Bertillonage; the Sûreté; recidivism; police photography

He must have been a disappointment to his father. Dr Louis Adolphe Bertillon was a well-known man about town. That’s quite an achievement bearing in mind that the town in question was Paris. Bertillon Snr was a distinguished medical doctor, inspector-general of ‘benevolent institutions, and founder member of the city’s school of anthropology. Today he might be almost forgotten were it not for his son.

There are no two ways about it: Alphonse Bertillon was a misfit. One of his biographers puts it this way: ‘[He was] a young man with a pale, thin, dismal face, slow movements, and an expressionless voice. He suffered from bad digestion, nosebleeds, and terrible headaches, and was so unsociable most people found him repellent. His reserve and taciturnity were accompanied by a suspicious nature, a strong tendency to sarcasm, bad temper, insufferable pedantry, and lack of aesthetic feeling. He was so unmusical that during his military service he had to count the notes in order to distinguish the bugle signals for reveille and roll call’[i].

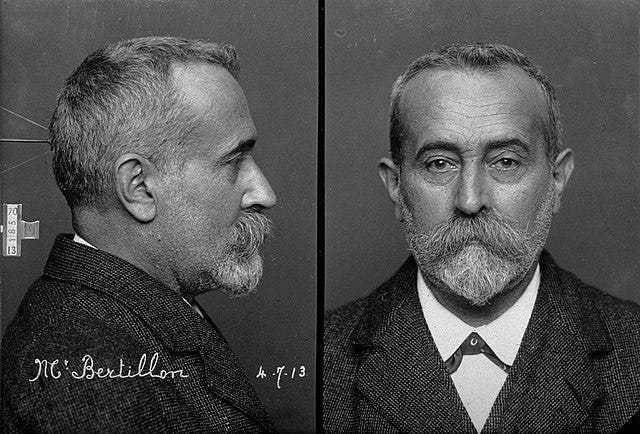

Young Alphonse just could not seem to get along with people. His father had sent him to the best schools France had to offer. They had expelled him. (No surprise there – he set fire to his own desk.) He’d tried to become a banker but the bank dismissed him. At length his name and his father’s reputation secured him an assistantship in the Prefecture of Police. That’s where Alphonse at last managed to create a reputation of his own. You can see a picture of Bertillon, as a distinguished older man, below:

Not that it was the kind of hothouse environment in which you’d expect young talent to thrive. To the contrary, you can imagine his superiors’ moustaches bristling with hauteur as they (the superiors, not the moustaches) presented him with his new workplace: a corner in a corridor. Apparently as unventilated as it was scorned, Bertillon's corner suffered all the notorieties of the Parisian climate. He sweated in summer but in winter his feet froze.

This unpleasant workplace had one great advantage for a young chap whose intellect everyone had always underestimated. The gendarmerie kept their filing cards close by. Indeed, part of Bertillon’s job was to completing thousands and thousands of these cards. He found himself recording vague and useless information: ‘tall’; ‘short’; ‘ordinary’; ‘no special marks’. To each card was attached a photograph, which you’d think would be an aid to identification. It wasn’t. That’s because early police photographers seemed to confuse themselves with society portrait-makers. Lighting, distance, aperture – none of these was uniform. Villains disguised their faces with snarls or grimaces. Not only that, but there were 80 000 photographs. Who had time to compare the felon they’d just arrested with every single one of them?

Criminals were forever changing their names and appearance. Not a policeman in Paris could hope to recognise them all. Old lags would sometimes pass themselves off as first-time offenders; infamous criminals might receive nothing worse than a warning. Branding – which might have worked – had been banned half a century earlier.

In the 1880s, Darwin, Lombroso, and Quételet were not exactly household names…except in the household Bertillon had grown up in. He’d always known all about them. He knew, too, that the remarkable trio of scientists had conducted their enquiries much like the officers of the Sûreté itself: they patiently gathered and collated data, and from it they worked out the answer to a puzzle. Plenty of data was available to Bertillon just an arm’s length away. Within a few months, he was using it all.

Bertillon stopped filling in the cards and started putting photographs side by side – cheek to cheek, jowl to jowl, ear to ear. He was on the trail of some important discovery. No one else understood what he was doing. Bertillon was so socially inept he seemed unable to explain. His colleagues sat around puzzled as he hunted down patterns that might yet provide a revolution in criminology.

Soon Bertillon was measuring criminals as they arrived for processing. Like some mapcap tailor, there he was to greet them at the door, hands shuttling about with tape measures and, one likes to imagine, lips bristling with pins. How the others laughed at poor old Bertillon as he meticulously recorded the criminals’ foot length, thigh circumference, arms, head... Oh yes, how they laughed.

I bet you can guess how this turns out. Bertillon was right and the scoffers were wrong. He ‘d seen something they had not. Or, rather, his data had told him the answer to a question they had not even thought to ask. Make enough measurements and you can identify your man. Two criminals might share a measurement or two, perhaps, but three? Four? Five? If you took eleven, it turned out the chances of two criminals sharing the same vital statistics were no less than 4,191,304 to 1. Take fourteen and you were talking truly galactic odds: 286,435,456 to 1. Bertillon added three more points: the colours of the eyes, hair, and skin.

These thrilling probabilities prompted Bertillon’s second report to the Prefect of Police, who had ignored the bumptious young man’s first one.

The Prefect read Bertillon’s report. He sent for the young clerk. Bertillon’s hour had come. His ship had come in. It was his belle epoque.

His hour ended, his ship left without him, his belle epoque stopped. Bertillon, as ever, had simply been unable to get his ideas across. He’d left the Prefect less knowledgeable at the end of the meeting than at the beginning. Worse than that - the Prefect got in touch with Bertillon Snr and told him to tell his son…well, he told him to tell his son exactly what people have been telling fathers to tell their sons ever since the first tribal elder burnt his fingers on one of those new-fangled ‘fire’ things.

Two years passed. A new Prefect appeared on the scene. Perhaps he was smarter than his predecessor; perhaps he simply didn’t want Bertillon uglying up his office any longer than necessary. Apparently – you can almost feel the perplexity and confusion in the words – he said this:

'All right, you'll have the chance to try out your ideas. From next week on we shall introduce your method of identification on an experimental basis. Two assistant clerks will be assigned to you. I give you three months' time. If during this period your method fishes up a single recidivist criminal... '[ii]

Bertillon returned to his corridor. You might think he’d have been pleased, but that is to underestimate Bertillon’s grumpiness. If anything, he was even more surly now than before. He knew that the new Prefect’s offer was like the flower that hides the serpent. The chances of the police managing to capture, measure, imprison, free, and recapture even a single recidivist just three months were slim to none. Still, it was the best offer Bertillon was likely to get, and he knew it.

November 1882. Paris must have been growing cold. Bertillon’s corner, however, may have been warmer than usual: not only was he exercising obsessively, by means of dashing to and fro, but now he also had two bemused clerks to warm his hands on. He also had a young lady, though whether he warmed his hands on her too, history does not record. Bertillon had met her while he was crossing the road. He offered her a job based on her nice neat handwriting[iii]. How exactly he found out about her nice neat handwriting, while they were crossing the road…well, history does not record that, either.

Before the end of February 1883, the Paris newspapers had a story all about Bertillon and a man who had claimed to be called Dupont after one arrest and Martin after a different one. (Dupont had been arrested, incidentally, for the not-very-heinous crime of stealing an empty bottle.) The delight was not Bertillon’s alone. His father died just a few days after receiving the news. Alphonse – that failure, that perpetual disappointment – had prevailed at last.

1884. Bertillon successfully identified no fewer than 300 recidivists: more than one every working day. No two of them shared the same measurements. The system was proven, it seemed. (Unwilling just to lie back and listen to the applause, Bertillon now ‘invented the mug shot’[iv].)

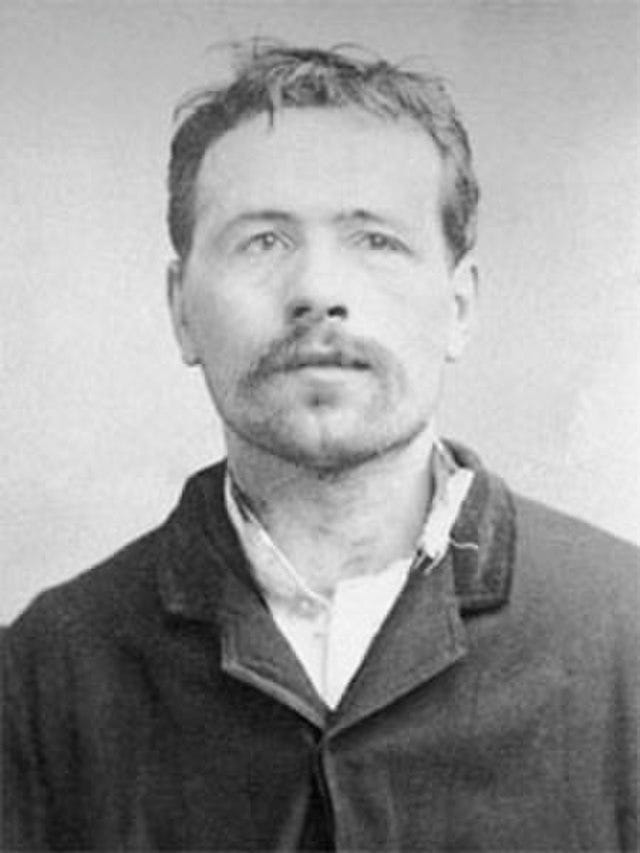

His system, known as bertillonage, helped capture the notorious anarchist, Ravachol, about whom ironical lyrics had been written - a tango in fact: ‘“Let’s do the ravachole/Hooray for the sound, hooray for the sound/Let’s do the ravachole/Hooray for the sound of explosion!”[v] You can see a picture of Ravachol below:

Dignitaries started dropped in. Bertillon grew famous. Indeed, soon he was as much a name in every French household as Darwin and Lombroso had been in his own.

‘Bertillonage is the greatest and most brilliant invention the nineteenth century has produced in the field of criminology.’ So wrote the French press. ‘Thanks to a French genius, errors of identification will soon cease to exist not only in France but also in the entire world. Hence judicial errors based on false identification will likewise disappear. Long live Bertillonage! Long live Bertillon!’

His superiors quickly placed Bertillon at the head of the Police Identification Service. In fact, the Service was created, it seems, for no other purpose than putting Bertillon at the head of it. Now, when dignitaries came to visit, Bertillon could make them climb endlessly up to his attic office and then stand around forever while they waited to see whether the crotchety celebrity would even bother to see them.

In 1902, Bertillon turned up in a Sherlock Holmes story, no less:

“I came to you, Mr. Holmes, because I recognised that I am myself an unpractical man and because I am suddenly confronted with a most serious and extraordinary problem. Recognising, as I do, that you are the second highest expert in Europe –”

“Indeed, sir! May I inquire who has the honour to be the first?” asked Holmes with some asperity.

“To the man of precisely scientific mind the work of Monsieur Bertillon must always appeal strongly.”

“Then had you not better consult him?”

“I said, sir, to the precisely scientific mind. But as a practical man of affairs it is acknowledged that you stand alone. I trust, sir, that I have not inadvertently –”

“Just a little,” said Holmes.

Better than Holmes? There is simply no higher praise. The irony is that by this time Bertillon was no longer, well, quite the same man.

Bertillon’s life had reached its highest point. There was only one way for it to go.

Why exactly was that? Well, you’ll have to wait till next week for the startling conclusion of our dramatic tale! To make sure you never miss a single exciting episode of Crime & Psychology, be sure to bash a blue button below. Beat it like a bongo! You know it makes sense!

You can check out Part 2 of the story here.

[i] Thorwald, Jürgen: The Marks of Cain, Thames & Hudson, London, 1965, p17

[ii] Camcasse, quoted in Thorwald, op cit, p36

[iii] Farebrother, Richard & Champkin Julian: ‘Alphonse Bertillon & the measure of man – More expert than Sherlock Holmes’, Significance, Vol 11(2), April 2014, pp 36–39

[iv] Farebrother, Richard & Champkin Julian, op cit.

[v] Quoted in Sante, Luc: The Other Paris, Faber & Faber, London, 2015, p179

I enjoyed this! Does anyone have any ideas why Bertillon was so grumpy? I'm curious why he set his school desk on fire, but maybe he didn't even know why himself.

Such a great read! As criminology lecturer I find these stories utterly intriguing