THE INCREDIBLE AND SAD TALE OF GRUMPY ALPHONSE AND HIS DOOMED SYSTEM FOR MEASURING CRIMINALS Part 2

Anthropometry; fingerprinting; prison; murder; detection; court appearances

In last week’s newsletter we saw how Alphonse Bertillon, champion grumpy young man of all France, put a career of idle desk-burning behind him and became famous throughout the world by inventing a system for measuring criminals to tell whether they’d ever been arrested before. When we were rudely interrupted (by the end of the newsletter), Bertillon’s career had reached peaked in a heady tricolore swirl of Gallic patriotism. Bertillonage was celebrated throughout the world. ‘Long live Bertillon!’ wrote the French journalists. The choleric genius had carte blanche to insult as many important people as he wanted and none of them could do anything about it. What could be more agreeable?

If you happened to miss Part One of this story, you can check it out here.

As one of his biographers has written: ‘It is a bitter blow to any discoverer to have his work superseded by a new advance just when it has won its victory. Such was the fate that overtook Alphonse Bertillon’[i].

But first came William West. Also, Will West.

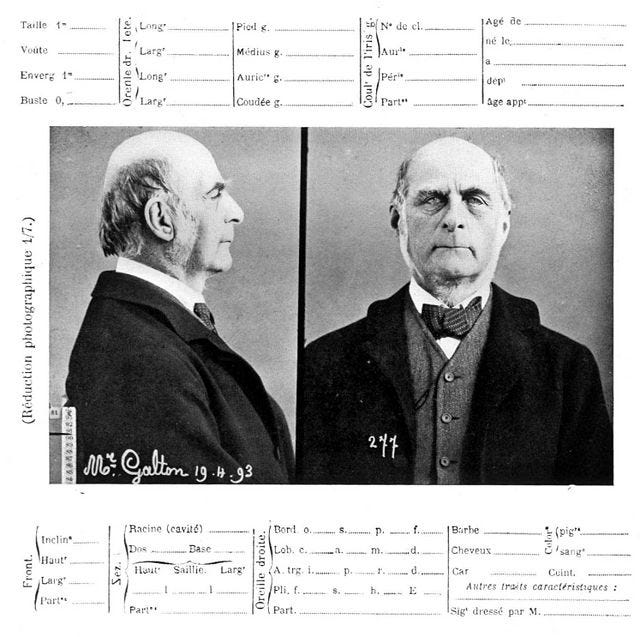

Bertillonage was being used extensively throughout the United States. In 1896, delegates at a conference in Chicago were surprised to discover that the country was home to no fewer than 150 ‘anthropometric laboratories’. (That word ‘anthropometry’ just means ‘measuring people’. It was terribly fashionable among scientists at the end of the nineteenth century. Its figurehead was no less a fellow than Sir Francis Galton, who once visited Bertillon himself and had his own anthropometric index card made. Galton is going to reappear in this story very soon.)

No one at the conference seemed unambiguously delighted with the system. Scientific and objective though it was intended to be, it was also clunky, time-consuming, and prone to error. There was also a practical problem: who was going to make the measurements? To function properly, bertillonage required strict discipline. The wardens of Sing Sing and Fort Leavenworth employed their own prisoners to do it. Perhaps it did not cross their minds that the prisoners might not be terribly motivated to get it right (quite the opposite in fact). Frustrated, the warden of Fort Leavenworth had even started experimenting with a new-fangled system called ‘dactyloscopy’ You and I know it as fingerprinting.

In 1903 the prisoners started filling out a measurement card for a new inmate called Will West (in case you ever need to know, it was number 3246). The guard went to the file to put the new card in the appropriate place. He discovered that Will West’s card was already there. It was number 2626.

The new prisoner was at least as surprised as the guard: Probably more so in fact since he’d never been in Leavenworth before. The guard sent someone to check. Prisoner No. 2626 was right at that moment in one of the prison workshops. This ‘prison fish’ was a different Will West: same name; same Bertillon measurements.

Now the warden got involved. He stood the two Will Wests side by side. Their own mother could surely have told them apart - but perhaps you or I would have struggled. The similarity was more than striking[ii]. If you’d like to check it out for yourself, click here to see pictures of the two Will Wests. Don’t forget to come back to Crime & Psychology once you have put your lower jaw back in its appropriate place.

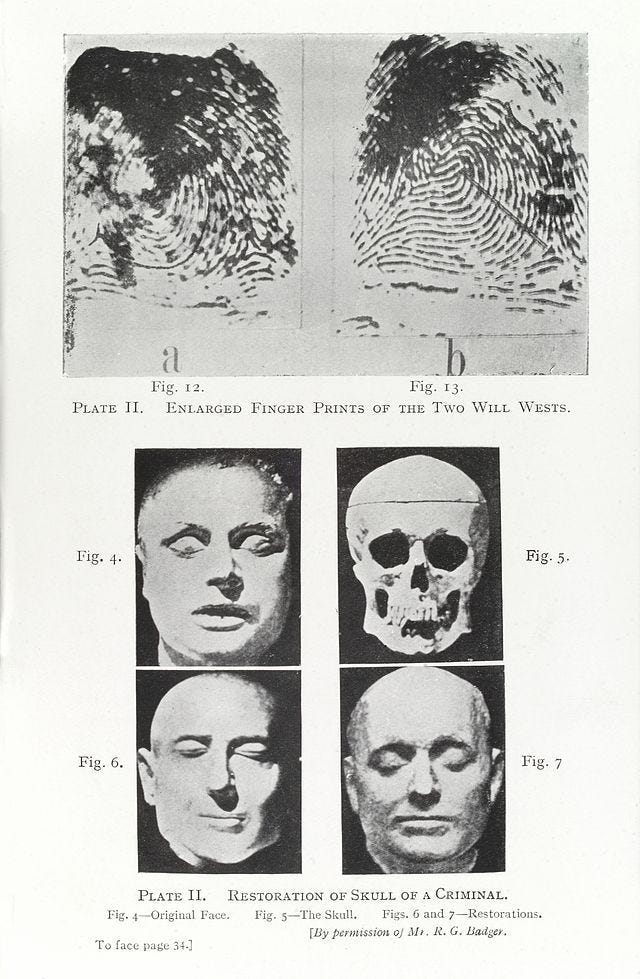

Although they were not absolutely identical, the two men’s Bertillon measurements were certainly pretty close, and certainly within the tolerance that the system usually allowed. ‘This is the end of bertillonage,’ said the prescient warden (or so we are told[iii]). Sending for his dactyloscopy kit, he compared the two men’s fingerprints. Just as you’d expect, fingerprinting succeeded where Bertillon’s elaborate system had failed. Here are the fingerprints of the two Will Wests:

No one used bertillonage at Fort Leavenworth again after that day.

Fort Leavenworth, as it turned out, was the first of many. Apostasy was everywhere. Bertillon fumed. His was not the personality to take defeat easily.

The world’s cradle of fingerprinting was Argentina[iv]. The work of a man called Juan Vucetich was absolutely vital. He’d begun his experiments as early as 1891. He discovered that even the lines on the fingertips of the mummies in the museums had survived intact after hundreds of years. This made police officers throughout the continent extremely enthusiastic, even though today we know that mummies were in fact committing extremely low numbers of crimes in South America at the time.

Fingerprinting spread swiftly from the New to the Old World. England, of course, turned quickly away from bertillonage because the system had been imported by no less influential a person than Sir Francis Galton. Ridges on the fingerprints are known as ‘Galton marks’ even today. From England, the system leached across Europe[v]. Every new country that fell was an agony to Bertillon. Featured below is Galton’s bertillonage card:

Secretly – doubtless muttering to himself the whole time – Bertillon began keeping some reluctant dactyloscopy records as well. He gave them the name of 'special marks', which makes you suspect he didn’t want to admit that they were really all that special at all.

Can we imagine his emotions on 17th October 1902? I’m not sure we can.

It was, of course, a day like any other. Bertillon went to photograph the scene of a regular, ordinary, humdrum murder. A man named Joseph Reibel had had been found dead in his dentist's office. It looked as though someone had staged the scene to make it look like a robbery, but police suspected that they were looking at a cold-blooded homicide. Bertillon noticed a pane of glass that had some fingerprints on it. He took it to his laboratory just because he was curious to work out how best to photographs the traces left on glass. It was the kind of technical challenge he enjoyed.

Evidently, Bertillon did a top job. The photographs came out well. Perhaps, for Bertillon’s taste, too well. On what was likely just a whim, he decided to look up these fingerprints in his small collection. It was a big old job he had set himself. The cards were filed not by dactyloscopy but by anthropometry, meaning that Bertillon and his assistants had days of boring work to do.

But there they were, the prints.

Bertillon had made a habit of recording only the thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers of the right hand on his cards. But those were exactly the fingers the murderer had used to handle the pane of glass. A man called Henri Leon Scheffer was arrested and confessed. We can imagine how Bertillon groaned.

No surprise, Bertillon seems to have played down the significance of the fingerprints. But there was nothing he could do to control the press, who quickly hailed him as the founder of an entire new science. One caricature showed him peering through a magnifying-glass at filthy handprints in a public toilet. You can imagine how happy that made Bertillon[vi].

This reversal may have depleted a large part of what little strength remained to him. Bertillon was sick and gowing sicker, it seems, day by day. He may have been little helped by his own obstinacy and arrogance as he reflected on the famous Dreyfus Affair.

This big political scandal had obsessed France for many years. (Even the great novelist, Marcel Proust, devotes far too many pages of his magnum opus, Remembrance of Things Past, to telling us about it.) Bertillon had agreed to act as an expert witness in the matter of handwriting. This was all well and good, except for the fact that he seems not to have known very much about it. Bertillon, in the words of one academic paper, ‘displayed all his arrogance, obstinacy and wrong-headedness – as well as more unpleasant characteristics and being flagrantly wrong besides’[vii].

Bertillon was not wholly responsible for the conviction of Captain Dreyfus as a German spy, but for sure his mistaken, incorrect testimony carried far too much weight. Partly on Bertillon’s word, Dreyfus was sent to Devil’s Island…and then he was brought back in a hurry. He was not a spy after all. Bertillon, however, even in his sickbed, refused to admit that he’d done anything wrong. Here is Dreyfus on Devil’s Island:

Twenty years earlier, Bertillon had received the red ribbon of the Legion of Honour for his great work. He wanted a rosette to go with it. The Minister of the Interior agreed, on one condition. Bertillon had to admit his error. Bertillon, dying, blind, but no less obstinate than ever, received no rosette.

Will Wests, Galton, & Dryfus pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References supplied so that you can chase up anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Thorwald, Jürgen: The Marks of Cain, Thames & Hudson, London, 1965, p116

[ii] The Will and William West case: The identical inmates that showed the need for fingerprinting, 1903 - Rare Historical Photos, Accessed 4th July, 2024

[iii] Thorwald, Jürgen, op cit, p134

[iv] Galeano Diego & Garcia Ferrari Mercedes: ‘The bertillonage in the South American world’, Revue Hypermedia, Histoire de la Justice, des crimes et des peines, 2011, Available at https://doi.org/10.4000/criminocorpus.402, Accessed 5th July2024

[v] Thorwald, Jürgen, op cit, p77-78

[vi] Thorwald, Jürgen, op cit, p120

[vii] Farebrother, Richard & Champkin Julian: ‘Alphonse Bertillon & the measure of man – More expert than Sherlock Holmes’, Significance, Vol 11(2), April 2014, pp 36–39

Those photos of Will West and William West are incredible.

"... even though today we know that mummies were in fact committing extremely low numbers of crimes in South America at the time." This made me laugh.

Seriously, though, what a sad ending for Grumpy Alphonse, made all the sadder by his obstinate nature. Thank you for sharing his story. It really is incredible.

Marvelous, we started looking into Vucetich a few weeks ago. We read about him in a book called, Civilizing Argentina. The book makes references to his developments in fingerprinting, taking, cataloging, studying, and so forth. An interesting point that we need to further explore is that the author claimed that Vucetich started to think that there were patterns shared among criminals and hence that it may be possible to predict who may in the future engage in crime.