Mimesis (n): ‘the act of representing or imitating reality in art…’[i]

The movie Dirty Harry (released in 1971) includes this striking scene: The police officer Harry Callahan, played by a rising star by the name of Clint Eastwood,[ii] strides past a cinema that’s showing the movie Play Misty for Me (also released in 1971) – a movie that also features a rising star by the name of Clint Eastwood. One can’t help but speculate about events in (the fictional version of) San Francisco. Do confused film buffs keep stopping Inspector Harry Callahan in the street and politely requesting Clint Eastwood’s autograph? The Inspector has doubtless encountered many cases of mistaken identity in his career, but surely this one is the most galling.

There’s a scene in the movie Zodiac (released in 2007) in which the police officer Dave Toschi, played by the established star Mark Ruffalo, goes to see the movie Dirty Harry, satarring Clint Eastwood. Toschi hetzes out. A colleague teases him: ‘Dave, that Harry Callahan did a hell of a job with your case’. ‘Yeah,’ Dave replies. ‘No need for due process, right?’ The real-life Dave Toschi also hetzed out of Dirty Harry before the end. Real life didn’t match up to the screen version. ‘He couldn’t take it,’ Ruffalo said. ‘It was so simplified’.[iii] Harry Callahan’s fictional case was based on the real-life case that Toschi was working.

Why does (the fictional) Toschi go to the movie in the first place? Doesn’t he have more important things to do? Well, Toschi’s been obsessing over the serial killer, Zodiac. His supervisor advises him to relax, go see a movie. He nips along to Dirty Harry. It’s an exclusive screening for the LAPD. Damn, the movie’s all about Zodiac! Even when he isn’t working, Toschi seems to be working. You think your job is tough? Toschi can’t catch a break.

In 1978, a promising young writer, (then a columnist at the San Francisco Chronicle,) named Armistead Maupin received an absolute avalanche of letters praising Toschi. And then he got one that didn’t. ‘That city pig Toschi is good, but I am smarter and better. I’m waiting for a good movie about me. Who will play me?’ The letter seemed to come from Zodiac himself. Or did it? Some claimed it must be a forgery from the desk of no one but – guess who - Toschi himself. Could the investigator possibly be the killer? Was he actually writing letters to the press advertising his own investigation of a series of murders that he himself had committed? And did he take a break from the whole complicated affair to go watch Clint Eastwood pretending to be him? Some people claimed nothing less. Perhaps they watched too many movies.

Toschi was reassigned away from Homicide. Life imitates art: just two years earlier, the same thing had happened to Inspector Harry Callahan in the movie The Enforcer. He broke the department’s rules one time too many.

You can sympathise. It’s late in his career. Harry has seen many terrible things. Perhaps his desk-jockey supervisors – smug and snug as they are - can barely imagine them. Harry is short of patience, with the criminals he has to take down every day as much as with the bureaucracy that taking them down inevitably entails. Harry wants to do good, but the pencil-necks seem determined to thwart him.

For all its marquee-friendly violence and box-office success, Dirty Harry is a movie that raises some awfully big, real-world questions, the kind we wrestle on a weekly basis, here at the Crime & Psychology Substack. Do the ends justify the means? Can we deter crime? And just how many rights must we accord to those who trample on other people’s?

The movie’s plot is short on complexities. San Francisco is being terrorised by a man called Scorpio. He murders an innocent woman and claims that only a $100K bribe will prevent him from doing it again. When he tries a second time, he is almost caught. He escapes but murders a child instead. Next, he kidnaps a young girl and doubles the ransom. Harry finds Scorpio and tortures him into revealing the girl’s location. Scorpio, playing the victim, demands that Harry respect his ‘human rights’. The police are forced to let the killer go (forcing the audience to start thinking about ‘lily-livered guidelines’ and so on). Minutes later, Scorpio hijacks a bus full of school children. Only tough cop Harry can stop him. At the last, our hero is seen tossing his police badge into a river. He’s as disgusted with the desk-jockeys, the bleeding hearts, and the pen-pushers, as he is with the serial killer he just saved them all from.

That torture scene is pivotal. Most of us, caught up in the narrative, are probably cheering for torturer Harry. We’re supposed to. We are also supposed to pause and ask ourselves whether we really should. Doesn’t Scorpio have rights? Could they possibly be more important than his victim’s? Do we want our cops to become vigilantes? How else are we to catch villains like Scorpio; like Zodiac?

Speaking of Zodiac… No doubt he was one of the most notorious real-life serial killers. He murdered at least seven - maybe more - young people in and around the Bay area at the end of the 60s. In a literature glutted with these pathetic specimens, Zodiac yet manages to retain some marginal mystique. It is partly explained by the fact that he was never caught. Like Jack the Ripper’s, his face is a screen onto which you and I can project whatever in the world we dislike the most. That made him a resonant choice for a big-screen baddie.

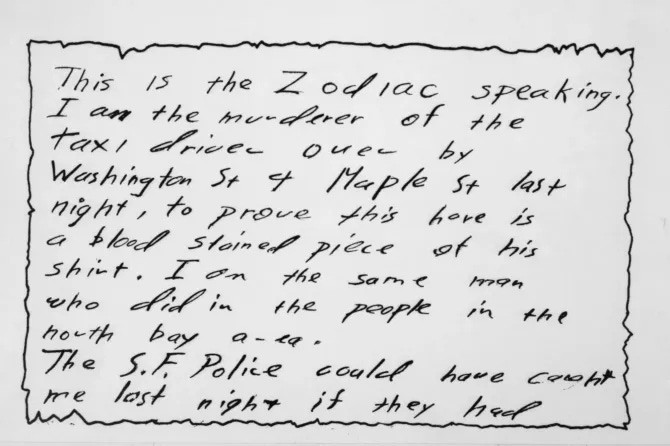

Mimesis again… Zodiac terrorised San Francisco. So did Scorpio. Zodiac was a terrifyingly new phenomenon. (In those innocent early 70s, serial killers had no hold on the regular citizen’s consciousness.) Scorpio shocked film buffs in exactly the same way. Zodiac had his own supervillain-style symbol – a circle with crossed lines. Scorpio sported a signature belt buckle that resembled a broken ‘peace’ sign, invoking, for your regular middle-class cinephile, not only the previous decade’s bewildering peacenik hippies but also the inescapable threat of nuclear catastrophe. Zodiac wore combat boots. So did Scorpio. Zodiac (one suspect, at least) was played in the movie by John Carroll Lynch, a bald guy in a t-shirt with a paunch. In the script’s early drafts, Scorpio was written as ‘a bald guy in a t-shirt with a paunch’.[iv] Zodiac left notes for the police. So did Scorpio. (If you’d like to check them out, Zodiac’s letters are here: Zodiac Killer Letters and Ciphers -- Codes, Cryptography.) Zodiac thought he was too clever to let those dumb old cops catch him. Scorpio did too.

Whether the police were really too dumb or too old is a matter of opinion. The film-makers certainly considered them way too soft, too liberal, too tangled in bureaucracy. They were incapable of shielding the public from the new horrors that were all about. Audiences agreed: Bureaucrats had no idea what life was like down on the streets where real life happened. Times were turbulent: anarchy threatened. Who could save them? Only a man like Harry Callahan: an old-fashioned type with values the bureaucrats couldn’t begin to understand. Harry wasn’t frightened of a rule-book and he remembered a time when his colleagues weren’t, either.

‘What I’m saying,’ Harry’s boss tells him, ‘is that man has rights’.

‘I’m all broken up,’ Harry replies, ‘about that man’s rights.’

Audiences nodded along. They were all broken up about them too. They knew all about bosses and managers. They knew all about rules and regs. Perhaps they even recalled the soulless, empathy-vacuum ‘pod people’ of Don Siegal’s earlier movie, Invasion of the Body-Snatchers.

The critics were scandalised. Well, you can imagine. Kinder ones called the movie ‘reactionary’. Others called it ‘fascist’. They called Harry Callahan a Nazi. (The Jewish director deliberately had Scorpio use only Axis Forces weapons: many viewers failed to notice.) Clint Eastwood – the real one - remained irritated for years. But, looking back, perhaps the movie wasn’t so reactionary after all. In at least one respect it was notably forward-looking. Perhaps even the director would have been appalled to know why.

In order to get the viewer on Harry’s side, Siegal had to ensure that Scorpio was bad as could be. He needed Spring-heeled Jack, the Joker, a demon… Harry’s behaviour had to be comprehensible, even when it included torture. Scorpio might not appear so horrifying today, to our jaded twenty-first century eyes, but remember this was 1971. Movie-goers had seen nothing like Scorpio.[v] Reportedly, they cheered when Harry brought him down.

You and I live in a world in which, (as Quentin Tarantino pointed out,) a show like Criminal Minds can introduce a depraved new serial killer every week for fifteen years and no one even flinches. But 1971 was 1971. Mindhunter was in the future. So were The Silence of the Lambs, The Bone Collector, Se7en, The Cell, Trap… Newspaper readers were aware of the Manson Family, yes, not to mention Richard Speck and the Boston Strangler – but serial killing was definitely on the weirdo shelf. It crossed fewer minds than, say the gold standard.[vi] Put on a map of Europe, it might correspond to Kotor or Harstad. Indeed, the term ‘serial killer’ would not even be invented (or imported from German[vii]) for another decade.

I mentioned the notes and ciphers that Zodiac left for the police, as if taunting their inability to catch him. In one of them, he actually did threaten to ‘shoot out the front tires’ of a school bus and then ‘kill the kiddies as they come bouncing out’.[viii] Just like Scorpio. That’s the world that Dirty Harry’s audience was adjusting to: a world in which ‘kiddies’ might be murdered as they came ‘bouncing out’ of a bus; a world in which the younger generation had fled to Haight-Asbury to turn on, tune in, drop out; a world in which Black Panthers used the money from the banks they robbed to buy the guns they posed with, prepped for some violent future no one could predict.

We are barely a few minutes into the film, in fact, before Harry foils just such a bank robbery. He acts so cool, he doesn’t even look heroic. Cinema audiences could relax: This is all in a day’s work for Harry! He doesn’t stop eating his hot dog, just blows the robbers away before delivering one of the most famous lines in movie history: ‘”Do I feel lucky?” Well, do ya, punk?’

‘It’s OK,’ a million scared viewers thought over their popcorn. ‘It’s OK. Harry’s here to protect us.’ The real police may not be up to snuff, but at least Don Siegal had magicked up an imaginary supercop to defend the taxpayer. How many debates do you think the movie sparked, in the city’s cars and bars after the credits rolled? ‘Dirty Harry,’ writes on commentator, ‘rendered San Francisco an important symbol for the debates between liberals and conservatives […] the film itself also became an active player in these very debates’.[ix] The director may well have shifted his movie’s location from Seattle to San Francisco precisely in order to spark just such discussions.[x]

It was a turbulent city and these were turbulent times. Everyone was talking about crime, housing, white flight, racial tension. The problem, the movie seems to insist, lay with the liberals - politicians and police. It was hardly alone (Klute, The French Connection, and Serpico all appeared within two years- and check out our post on Death Wish), but only Dirty Harry was provocative enough to suggest that vigilante cops might be the solution. Provocative, or stupid, depending on your point of view.[xi]

The lead actor’s career was assured. But it was a different story for Andrew Robinson, who played Scorpio. He was a real-life victim of his own on-screen success. Robinson was so successful, in fact, you’ve probably never seen him again. Cinema audiences could see nothing but Scorpio. Robinson was forced to unlist his telephone number. People kept confusing the actor with his make-believe character and calling him with death threats.

You have to wonder whether Zodiac himself, like Dave Toschi, went to see Dirty Harry. I bet he did. Serial killers do love the limelight, especially those who, like Zodiac or Scorpio, seem to be motivated by power. I bet Zodiac loved watching all those people queue for the movie – for his movie. Remember that cliché, about killers revisiting the scene of the crime? It happens in real life as well as the movies.

In Zodiac, Toschi gets the nickname Bullitt. That’s a reference to the movie of the same name, starring Steve McQueen. McQueen modelled Bullit’s personality and sartorial style on Toschi. One character in Zodiac remarks, ‘He wears his gun just like Bullitt’. Another replies, ‘No, McQueen got that from him’.[xii]

Take a breath: There you have a real actor who’s playing a fictional version of a real-life detective in a made-up movie, telling the truth about how another real actor, playing a made-up character in a wholly-fictional movie, modelled that character after the real-life detective who is being played by a real-life actor on screen with them in their own made-up movie. About real life.

Steve McQueen was offered the role of Dirty Harry but turned it down because he was busy making Bullitt. In fact, it was McQueen who recommended Eastwood for the role that neither you nor I can imagine anyone else playing. The producers wanted Frank Sinatra.

Zodiac (I mean the movie, not the real-life killer) was directed by David Fincher. So too was Se7en, a movie about the deadly sin of envy. Zodiac, (the character in the movie, not the real-life one) may have been motivated by envy, which is known as ‘the desire that imitates desire’. That very sin was incarnated by Kevin Spacey in Se7en. His character, John Doe, is ‘a highly stylised and focused version of the Zodiac’, even to the point of leaving messages for the police. Zodiac’s confirmed victims match the number of deadly sins. They are all young lovers who fill him with desire at the same time as they emphasise his feelings of neglect. ‘Desire,’ one author says, ‘is always fundamentally mimetic’.[xiii]

You can read about the Death Wish movies here.

All pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything that seems interesting.

[i] MIMESIS | English meaning - Cambridge Dictionary

[ii] A ‘rising star’ in the USA, at any rate. European audiences knew all about him from the Dollars trilogy, in which Eastwood played the Man With No Name who had three names.

[iii] Dave Toschi Obituary, The Times, Thursday February 01 2018, Available at Dave Toschi

[iv] Street, Joe: ‘Dirty Harry’s San Franciso’ in The Sixties - A journal of history, politics & culture, 22 June, 2012, note 50

[v] By 1974, they’d accepted their fate. That was the year Charles Bronson bypassed the police altogether and took the law, not to mention an array of large guns, into his own hands in Death Wish.

[vi] Quentin Tarantino on Clint Eastwood's Dirty Harry | Cinema Speculation - YouTube

[vii] Check out my own post on the Dusseldorf Vampire, here THE DüSSELDORF VAMPIRE AND THE EARLIEST DAYS OF OFFENDER PROFILING Part 2

[viii] ‘Nancy Drew’ – Zodiac Killer case – ‘Dirty Harry’, available HERE Zodiac Killer Case - Dirty Harry [ Clint Eastwood 1971 movie ]

[ix] Street, Joe, op cit, pp1-12

[x] Sides, Josh: Erotic City - Sexual revolutions and the making of modern San Francisco, Oxford University Press, USA, 2009, p167

[xi] Street, Joe, op cit, pp1-12

[xii] Yagoda, Ben: ‘”Dirty Harry” in ‘Zodiac”’, Movies in Movies, March 13, 2018, Available at: “Dirty Harry” in “Zodiac” – Movies in Other Movies

[xiii] Kevorkian, Martin: ‘The Danteseque desires of David Fincher’s Zodiac’, in Matthew Sorrento & David Ryan (eds): David Fincher's Zodiac: Cinema of Investigation and (Mis)Interpretation, Rowman & Littlefield, New York, 2022, pp150-166

What a fabulous and deeply contextualized take on a film I love to watch and don’t like to think about why I love to watch it! It’s an interesting point about Andrew Robinson. I was a huge fan of his performance on Star Trek: Deep Space Nine as Garak before I realized he also played Scorpio—his face is swaddled in prosthetics. And wow surprise appearance by Armistead Maupin! Another fave!

Jason: The sound you hear in the background is my mind working away after one read of Dirty Harry. Mimes and templates and what works inside the average human mind. There seems to be a wave of thinking about this moment in history, with the sudden emergence of a leader who is hugely disruptive of an established order that has worn out. Is he hero? Is he antihero? Is he villain?

This is the kind to stuff I love to contemplate. I will have more reactions as I wrestle with my own Dirty Harry who actually worked inside a bureaucracy that used Hobbesian Dirty Harry tactics. I think I mentioned that under Hoover, street agents operated on the belief they could do literally anything, as long as it was ordered by The President, The Attorney General or The Director himself. That era was coming to an end in the 1970s, when my story took place. Courts and civil libertarians (the old-school kind) were trying to reel the Bureau in and ultimately did so but only after the Establishment worked out a compromise that would allow court-sanctioned wiretaps and microphones and further would allow the introduction of evidence gathered in that way to be used in court. Another part of the compromise was the creation of RICO, the law that recognized there were bad guys out there who had banded together. There are still FBI squads that install "wires" and "read other peoples mail." They just do it with the permission (at least usually) of a court. FISA courts are an example.

So we have a new world today, and new jurisprudence. Formally-denominated terrorist organizations like Tren de Aragua and MS-13 can be investigated by hard-case cops with the formal approval of the courts. Probably a good thing, or at least necessary. But also detrimental to individual rights. Your question about how far the hero can go and still maintain the respect of the citizenry is as viable as ever. It started, in my view, with Hobbes, the authoritarian, versus Locke, the liberationist. And we still haven't answered it definitively.