THE DüSSELDORF VAMPIRE AND THE EARLIEST DAYS OF OFFENDER PROFILING Part 2

Murder; offender profiling; police investigation; arson; torture

Welcome back, Crime & Psychology fan! This week we complete the tale of Peter Kürten, who was one of the worst, and yet, in his own way, one of the most typical, serial killers of the last century. Last week, we saw how Kürten’s childhood resembled that of many modern serial killers and how his first spate of murders was interrupted by a prison sentence for an unrelated crime. Now we’ll pick up the story from the point at which Kürten began communicating with the police. For context, the first paragraph this week repeats the final paragraph from last week.

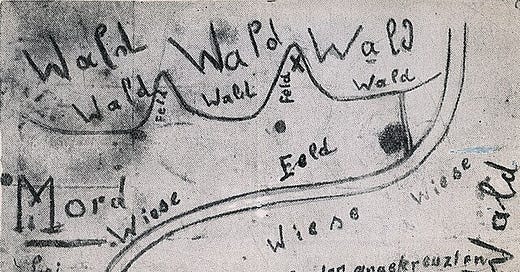

Düsselfdorf was soon ‘in a state of panic’.[i] Over the next several weeks, the violence and frequency of the attacks did not diminish. This is another common feature of serial murders. It’s as if the jaded killer needs his exploits to become more and more lurid in order to provide the same thrill. Kürten began to send the police details - notes and maps – to tell them where the bodies could be found.

Notes, maps, and so on are a ‘standard part of many serial murder cases’.[ii] Jack the Ripper, for instance, is believed by many Ripperologists to be the actual person who sent the various notes that have been attributed to him (as with everything Ripper-related, there is some controversy).[iii] Later, Kürten would express his admiration for his notorious predecessor. David Berkowitz, the Son of Sam, left notes at crime scenes, wrote to newspapers, and drew diagrams on his apartment walls.[iv] Much of the Zodiac Killer’s notoriety rests on the impenetrable coded messages he sent to investigators. And then there’s Dennis Rader, the BTK Killer, who was caught because of the increasingly-narcissistic and self-regarding notes he sent. (He mailed a floppy disk to a television station. Police simply checked the disk’s metadata and found that it was last modified by ‘Dennis’. Serial killers are rarely geniuses.)

Many serial killers seem to idolise their predecessors. If Kürten had the Ripper, Rader had Harvey Glatman, the ‘Lonely Hearts Killer’ of 50s Los Angeles. Glatman used to entice women to his apartment with offers of modelling jobs, tie them up, and dump their bodies in the desert. ‘It was all about the rope’,[v] Glatman used to say. He meant that the rope gave him control. It gave him power. Kürten, Rader, Glatman: they are under-achievers all, powerless losers who live to impose themselves on the most vulnerable people they can imagine. From fantasies to animals to human beings, it’s always all about the rope.

The Düsseldorf Vampire proved elusive. Ernst Gennat, director of Berlin’s criminal police, came to help catch him (his name is variously spelt ‘Genhert’ and ‘Gennart’ in the literature). Gennat’s brief profile is one of the very first in the literature. What kind of a person should the police look for? Gennat wrote a paragraph. (Incidentally, Gennat is sometimes identified as coining the term Serienmörder, which means ‘serial murder’.)

From the killer’s description of the crime scene I deduce that he is familiar with Düsseldorf. The killer seems to have been in close contact with his victim prior to the attack. This means that he is perceived as friendly and good-natured by the people who are in contact with him. They’d never suspect he was a killer […] The killer has shown exceptional cruelty in his attacks. He is sexually abnormal and has a history of mental illness. He must be mad.

Gennat presumed that the man must have a history of mental illness. Surely it must be recorded somewhere. On his recommendation, the police went to look through records at various psychiatric institutions, hoping to locate a suspect. They found nothing.

That must have been a disappointment. After all, Gennat’s logic appears sound enough on the face of it. most of us might agree that a person must be mad to commit such attacks. When we hear about extraordinary crimes today, many of us react in the same way: Psychiatric institutions must be a sensible place to look.

A moment’s though, though, and we might notice that our reasoning is faulty. As one criminal profiler has argued, it can be an error to confuse sadism with insanity. Just because a killer gets pleasure from hurting others we can’t be sure that he lacks all contact with reality. ‘Indeed,’ writes David Canter, ‘the assumption that the offender would be familiar with the area and not threatening in his appearance, both reasonable assumptions from how and where the crimes were committed, also suggested that the killer was able to present himself to others as a normal, plausible person. It is not easy for an insane person to simulate these characteristics’.[vi]

Indeed, the reasoning may not just be faulty: it may be circular. How do we know the killer is mad? Because of what he does? And why does he do what he does? He must be mad. We are never going to get very far on a train of thought like that. Indeed, when Kürten was finally caught and tried, he tried to enter a plea of insanity. The court would have none of it. Several experts testified that he was responsible for his actions at all times. Kürten was found guilty on all of the sixteen charges against him.

It's worth thinking a moment about the capture. A survivor named Maria Budlick led police back to Kürten’s home. Even in the presence of these officers of the law, she was too frightened to identify her attacker. Kürten, however, knew his time in freedom was limited. He moved out and into hiding. He told his wife about his double life as the Düsseldorf Vampire. Later, he confessed: ‘She raved that I should take my life, then she would do the same, since her future was completely without hope’.[vii] But – like, say, Fred West, who maintained that his wife, Rose, was innocent, and may even have killed himself to protect her – Kürten decided that his wife must be taken care of. He told her that she must be the one to turn him in and collect the large reward the police had posted for the notorious criminal:

‘Of course it wasn’t easy for me to convince her that this ought not to be considered as treason, but that, on the contrary, she was doing a good deed to humanity as well as to justice. It was not until late in the evening that she promised to carry out my request, and also that she would not commit suicide. It was 11 o’clock when we separated. Back in my lodging, I went to bed and feel asleep at once.’[viii]

While awaiting trial, Kürten spoke at length to the psychiatrist, Karl Berg. You might think he’d be ashamed, but far from it. Again, Kürten’s willingness to speak is far from unusual. The main difficulty with some serial killers seems not to be getting them to confess so much as convincing them to shut up. Dennis Rader, the BTK Killer, was not dissimilar: he seemed keen to share and show off, as if murder were some kind of accomplishment in life. Rader could not ‘bear to let his brilliance go unrecognized by the public’.[ix] The public, of course, just thought he was a murdering asshole.

Apparently the first thing that struck Berg was the ordinariness of the man in the cell in front of him. He’d expected to see ‘a gibbering lunatic, the wreckage of a man whose mind had given way to madness’.[x] But Kürten was polite, well-dressed, mannerly, and seemingly diffident. Was that better or, maybe, worse? Either way, he gave Berg the opportunity to conduct the first face-to-face psychiatric interview of a serial murderer.

What did Berg learn? For one thing, Kürten seemed to have excellent memory for his crimes. He provided details of no fewer than 79 different cases, including thirteen murders, for which he had not yet been accused.[xi] Like many serial killers, he may have been turning these crimes over in his mind for years, living off the remnants of the thrill they gave him. Kürten seemed intensely introverted, or, at least, wrapped up in himself. He’d even provoke his guards until they sent him into solitary confinement. He preferred it there, because he could indulge his violent, sexualised fantasies undisturbed.

Indeed, ‘sexualised’ was the word: ‘as he recalled the killings in grisly detail, [Kürten] exhibited all the signs of arousal, confirming Dr Berg’s belief that the sadistic tendencies were sexual in origin’. He was narcissistic and also psychopathic – by which psychologists mean that there are shallow emotions, lack of empathy and remorse, grandiosity and superficiality.

His crimes exemplified a phenomenon the Germans called Lustmord, which is exactly what it sounds like: murder for sexual pleasure. It may have been the new, defining crime of Weimar Germany, a society with a slaughtered generation, short rations, and a lost war to process. The lust-murderer took the form of Fritz Harrman, who butchered the bodies of at least 24 young males and sold the joints for meat. He appeared in famous artwork by Otto Dix and George Grosz (who was responsible for Self-Portrait as Jack the Ripper).

If it was the first time Germany had seen murders like that, it would certainly not be the last. Serial murder, some have argued, seems to be a symptom of capitalism and industrialisation. Serial killers have historically come as part of a package that includes industry, labour forces, and transportation networks. Some suspect that when a brand-new crime appears, it’s like a surface tremor that indicates the deep-down shifting of geological plates.[xii] Look at Juárez in Mexico. At one time, it was said to be a model for the developing world. Its closeness to El Paso, USA, marked it for prosperity. Shantytowns appeared to house the worked that Juárez attracted. And then a serial killer appeared, or maybe more than one. Women died by the dozen.[xiii] India and China, too, have seen their first serial killers in recent decades.

Berg’s book was called The Sadist. It became something of a classic in the literature, influencing the way we think about serial killers even up to the present day. It also influenced Fritz Lang’s famous film, M, starring Peter Lorre: once seen, never forgotten.

On 22 April, 1931, Kürten was sentenced to death nine times plus a redundant period of penal servitude. The death sentence was carried out on 2 July.

During one of his last conversations with Berg, he asked whether his served head would still be able to hear the blood rushing from his torso. This - explained the man who’d become known as a vampire - would give him his ultimate sexual pleasure.

All pictures courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything that looks particularly interesting.

[i] Murray, William, op cit, p1950

[ii] Gibson, Dirk C: Clues from Killers – Serial murder & crime scene massages, Praeger, Connwecticut, 2004, p2

[iii] Gibson, Dirk C, op cit, pp147-172

[iv] So, at least, the story goes – the Netflix documentary series, Sons of Sam, makes a good case that Berkowitz may in fact have been a patsy for other, even darker, criminals.

[v] Harvey Glatman quoted in Douglas, John & Olshaker, Mark: Mindhunter – Inside the FBI elite serial crime unit, Arrow, London, 2017, pxxi

[vi] Canter, David & Young, Donna: Investigative Psychology – Offender profiling & the analysis of criminal action, Wiley, West Sussex, 2009, p67

[vii] Peter Kürten | Murderpedia, the encyclopedia of murderers, Accessed 26th September 2024

[viii] Peter Kürten quoted in Roland, Paul, op cit, p30

[ix] Douglas, John & Olshaker, Mark, op cit, pxxiv

[x] Roland, Paul, op cit, p24

[xi] Ramsland, Katherine: Confession of a serial killer - The untold story of Dennis Rader, the BTK killer. University Press of New England, 2016, p5

[xii] Wilson, Colin: A Criminal History of Mankind, Granada, London, 1984, pp607-9

[xiii] English-language sources are thin on the ground, but here is a good place to start: 400 Dead Women: Now Hollywood Is Intrigued - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

Thank you very much for this essay on Kürten. This was, again, a great read.

Gennat's (false) assumption that the murderer must be mentally ill was certainly influenced by the Zeitgeist, according to which many things sexual which were out of the ordinary were considered mental illnesses or symptoms of such (including homosexuality, masturbation, prostitution, etc.).

By the way (since I have written about geographic profiling before): The murders described in Gennats article are a good database for practicing GP. Kürtens adress is known, and can be used to evaluate the geographic profile. This is particularly interesting since Gennats article does not contain all crimes commited by Kürten. Of course, a few crime sites can only be approximated, as the urban environment changed since then. But it is a nice practice.

Shocking story about this man. I think in trying to portray these individuals as monster as clearly deviant whether inside/out we also seek to distance ourselves from the randomness of life. If my neighbor can be a serial killer then I am never safe -- if killers are monsters then we can more easily identify them, we can more easily remain safe. Conversely, if killers are just like the rest of us -- then any one of us could engage in such activities... and that may also be hard to grapple with.

The finishing detail about his curiosity of his own death is really rather dark.