‘Why are we even talking about this? Everyone knows that crime is caused by poverty.’

There I was, minding my own business, delivering a lecture on the effects of media violence: does it lead to violence in the real world? That was when one of the students asked me that question.

I forget my exact reply. I probably waffled a bit, just as UK’s New Labour party politicians did when asked to explain their shiny-new slogan, ‘Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’. The fact is, the question opened up a big old rabbit-hole (we’re going to see plenty of them in this newsletter. Let’s avoid them). Even in a two-hour lecture slot, I couldn’t begin to do it justice. Afterwards, I moaned over coffee with a fellow psychologist who understood my pain. If I remember rightly, there was chocolate cake.

The two of us talked about ‘causation’, and how difficult it is to establish. It’s even more difficult for psychologists than for other scientists, confronted as we are by the intricate web of problems that we call human behaviour. (Albert Einstein once said how glad he was that he was not a psychologist, because Psychology is so difficult. I like to tell my students that, too. I mention it at least once in every lecture.)

Anyone who has read the history of Weimar Germany - with its barrowloads of worthless cash, grocery-store queues like actual constellations, its theft, serial murder, and the rise of Naziism – anyone who has read about that might be tempted to agree that poverty sure does seem to cause crime. I’ve included a somewhat startling picture that shows one of those queues. But even so, a scientist who tells you that they know the ‘causes’ of crime is like a missionary who tells you they know what happens after we die. They’re either a charlatan or a fool or both.

Let’s see what science can tell us – and what it can’t – about the causes of crime.

As you can imagine, there’s a certain amount of debate about exactly what ‘science’ is. You’ll be delighted to learn that I’m not going to address that topic in any detail here. We’ll never get to the end of it. But let’s take as our starting point the view, shared by many philosophers, that science is a set of methods designed to discover the causes of things. Science, after all, is in the business of explaining why things happen, and that’s essentially the same as saying what causes them. To explain why Donald came late to the meeting is essentially the same as to explain what caused him to be late. To explain why the cars crashed is to explain what caused them to crash. To explain why the terrorists bombed the building is to explain what caused them to do so. And so on.

It’s the same for every science. A meteorologist might want to know what causes storms; a physicist might want to know what causes the bizarre quantum behaviour of photons; an economist might want to know what causes recessions.

Here is a side note. You can skip this bit if you want to get straight to the Psychology stuff, but I think it’s interesting. The Greek philosopher, Aristotle, (sometimes known as ‘the Father of Science’) believed that there was not just one type of cause. There was a whole family of them. The four family-members were called ‘material’, ‘efficient’, ‘formal’, and ‘final’.

Three of Aristotle’s four family-members may seem peculiar to you or me. They may look a bit out of place at the birthday party or round the Christmas table – they don’t look quite like they belong. Who actually invited them? Should we offer them a piece of cake? When will they leave? At any rate, here they are, the country cousins, the family oddballs: The ‘material’ cause is the ‘substance out of which the object is made’. Aristotle’s example was the bronze in a statue. You and I might struggle to see that as a ‘cause’ at all.

The ‘formal’ cause effectively just says what a thing is. ‘Theft’, for example, is when someone takes something that belongs to another person, without their permission.

The ‘final’ cause is the purpose for which an something is made or created. The ‘final cause’ of a gun, therefore, is shooting; the ‘final cause’ on an acorn is to grow into an oak tree. ‘Final causes’ had a big influence on St Thomas Aquinas when he was putting together his ideas about demonology and changing the course of European history. (I discussed that in an earlier newsletter).

So much for Aristotle’s first three causes. For you and me, and scientists the world over, the ‘efficient’ cause is the one we recognise. It’s the one that looks like it belongs. More than any of the other three, the efficient cause feels like what we mean when we use the word ‘cause’. It simply refers to the action of one thing on another. What’s the cause of an eclipse? The moon passes in front of the sun and blocks its light. What is the cause of interpersonal violence? Too many violent video-games (well, maybe).

Many centuries after Aristotle, another philosopher, David Hume, claimed that causality isn’t real, just something that we imagine. I told you there would be rabbit-holes. Let’s avoid that one, as well.

How do we establish these ‘efficient causes’? There is only one way, and there can be no other. We need a controlled laboratory experiment.

Now, that word ‘experiment’ is a booby-trap. That’s because its use in science is different from its use in everyday life. If you or I say something like, ‘I’ll experiment with extra yeast in this bread recipe’, or, ‘Let’s experiment with this mysterious-looking mushroom,’ we are referring to some course of action we may possibly take, the results of which we can’t predict. In this sense, it’s an ‘experiment’ because the outcome is uncertain.

That’s not quite what scientists mean.

So what do they mean? Well, they use plenty of complex jargon, but, at bottom, when scientists talk about an experiment, they really just mean changing one thing and measuring something else.

That’s all.

Changing one thing and measuring something else – what could be simpler? If you have done that, you have done an experiment. If you have not done that, you have not done an experiment. (That second point’s vital. You can’t ‘do that’ when it comes to, say ‘poverty’. We’ll soon see why.)

I mentioned jargon. Like a ringwraith or a guilty conscience, jargon is always pursuing you. It permits scientists to talk to each other in a precise, technical way that incidentally prevents regular people from butting in on their conversation. Let me mention just one piece here. Those ‘things’ (the ones you change or measure) are known as ‘variables’. The one you change is called the independent variable (or IV). The one you measure is called the ‘dependent variable’ (or DV).

What does all this add up to? Simply this: If you don’t investigate the relationship between an independent and a dependent variable, you have not done an experiment. And if you have not done an experiment, you have not established causation. You simply cannot know that one variable causes the other (you simply cannot know that poverty causes crime, for instance). It may do, of course – but you can’t know that.

Another vital point: When scientists do an experiment, they need to know precisely what their variables are. That’s sometimes less simple than it sounds.

In the aftermath of shocking and apparently meaningless crimes like, say, those of Jimmy Savile or Lucy Letby, one common reaction is simply to ask ‘Why did they do it?’ What we seem to mean by that question is something like, ‘What caused these people to commit unimaginable crimes, and on such a vast scale?’

There’s only one way to find out, and that is to conduct an experiment.

A moment’s thought, though, and we may realise that we can’t even start to design our experiment until we’ve asked a follow-up question: What kind of answer are we looking for, exactly?

Take a look back at our original question: ‘Why did they do it?’ It could hardly be more ambiguous! Anyone would be forgiven for asking us what we mean by ‘why’? Are we asking what Savile or Letby were thinking when they committed their crimes, or are we asking which brain structures were active at the time, or whether they’d suffered some sort of childhood trauma that somehow magically ‘explained’ their adult behaviour?[i] Or are we – like Marxist criminologists - asking a broader question about their sociopolitical or economic environment and its reflection in individual behaviour?

Science only ever discovers the kind of causes it is looking for.[ii]

Let’s see what kind of questions a good solid experiment can answer.

Back in the middle years of the last century, good citizens were growing concerned about the causes of what they believed to be an epidemic of violence among young people. They suspected that exposure to television violence might be to blame. In 1963, the psychologist Albert Bandura decided to look into it.

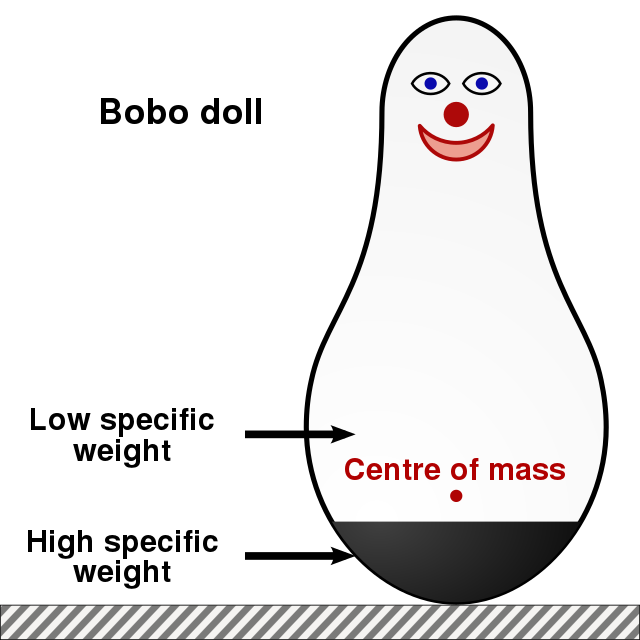

Because they wanted to establish causation, Bandura and his colleagues naturally carried out a series of laboratory experiments. The basic approach was this: Children came one child at a time to Bandura’s laboratory at Stanford University to play with a Bobo doll. In case you aren’t familiar with that particular piece of highly-sophisticated Psychology equipment, a Bobo doll is really just a big balloon with a face painted on it. I found you a picture. The doll’s entire repertoire consists of standing back up again when you knock it down. Fun for all the family.[iii] Before these breathlessly-excited children were allowed into Bandura’s laboratory (with what we can only imagine to be its carnival-like atmosphere) some of them watched an adult model fight the doll. Others did not. The psychologists observed the children to see how aggressively the two different groups behaved towards the doll.

Now a momentary jargon-break: The IV, in this case, was whether or not the children saw the adult model fight the doll. The DV was how aggressively they themselves behaved. We have ourselves a laboratory experiment!

Do you know any children, or were you ever a child yourself? Then you can imagine what happened. There was (no surprise) a difference between the groups. Children who had seen the model behave in an aggressive manner acted more aggressively than those who had not. Bandura and his colleagues therefore could be confident that exposure to aggressive behaviour caused the children to behave that way.[iv]

(Of course, the effects of modelling were very short-lived. Who knows whether the children would still have behaved aggressively twenty minutes later, or twenty hours, or twenty years? Smacking a Bobo doll is definitely not a recipe for a life of crime.)

Bandura and his colleagues, then, carried out a proper controlled laboratory experiment. They therefore learnt something about the causes of the children’s aggressive behaviour.[v] That’s simple enough to do when what you are interested in is straightforward variables like these. It’s a whole other matter, though, when it comes the topic we started out with - poverty and its effect on crime.

For one thing, neither ‘poverty’ not ‘crime’ is a variable. A variable, (to state the obvious,) has to vary. A crime is just a crime. It’s a thing. An armed robbery, let’s say, doesn’t ‘vary’. Neither does a kidnapping, or a murder, or case of insider trading. They aren’t variables. ‘Poverty’ isn’t a variable, either. It’s just a regrettable phenomenon. There is just no way to slot phenomena like that into an experiment. (Even if we could, obvious ethical problems would remain. No Psychology department in the world is going to let you run a laboratory experiment, no matter how well controlled, in which the outcome is, or may be, crime.)

Let’s go back to the claim that we started with - ‘Everyone knows that crime is caused by poverty’. The fact is, everyone does not know that. It’s just not something that’s amenable to being known. Why?: Because it’s impossible to carry out a controlled laboratory experiment.

This problem is not exclusive to Psychology, of course. An economist is going to be stuck when it comes to establishing the causes of economic recessions. A zoologist is going to be stuck when it comes to establishing the causes of species extinction. These are simply not things a person can know. Scientists can make guesses, look for patterns in the data, see whether one variable tends to go with another variable, and do all sorts of fancy statistical analysis, but they can’t actually know about causation. (This is the reason, incidentally, why tobacco-company executives can keep a straight face while they say, ‘I don’t know whether smoking causes cancer’. In a strictly technical sense, they have a point. Two famous academics who came a cropper here are the statistician, Ronald Fisher, and the psychologist Hans Eysenck, whose work I featured in an earlier newsletter - (2) CRIME & PERSONALITY - by Jason Frowley PhD (substack.com))

Here are some questions we may be able to answer using laboratory experiments:

Does viewing adult aggressive behaviour cause children to behave more aggressively, in the short term, under laboratory conditions?

Do misleading questions asked in a police interview cause the eyewitness’ recollections of the crime to change?

Why do some mock juries reach verdicts more quickly than others?

Under certain circumstances, participants believe that bystanders would intervene to aid the victim of a crime. Under different circumstances, they believe they wouldn’t. Why?

What causes certain newspaper reports of crime to be more engaging than others?

And here are some questions we may not be able to answer:

Does poverty cause crime?

What has caused the recent increase in inner-city stabbings?

Is psychopathy caused by frontal lobe damage?

Why do introverts and extraverts commit crime at different rates?

Why did Person X steal a wallet from Person Y?

What causes bad things to happen to good people?

You may notice that the first set of questions is more wordy than the second. It’s not difficult to see why. As I mentioned above, when looking for causes, we need to specify exactly what our questions mean. That simply takes up words. Scientific hypotheses are sometimes clunky to write and off-putting to read. That’s a consequence of their very specificity. (Perhaps you’ve noticed that legal documents often have the same quality. It’s for exactly the same reason.)

Now, you might say this: ‘OK, I understand your point about experiments and such. But one thing we do know is that crime (of certain kinds, anyway) is more common in places where poverty is high, and less common where it is low. That certainly tells us something’.

Well, if you say that, I’ll agree with you. It does tell us something. Unfortunately, that ‘something’ doesn’t have anything to do with causation. It simply tells us that the two phenomena (poverty and crime) go together (or, to use the technical term, ‘correlate’). For sure, that may give us a good reason to investigate them in more depth. But that’s all.

You may have heard the expression ‘correlation does not imply causation’. The fact that two phenomena go together does not tell us that one caused the other. More about this in another newsletter, at another time.

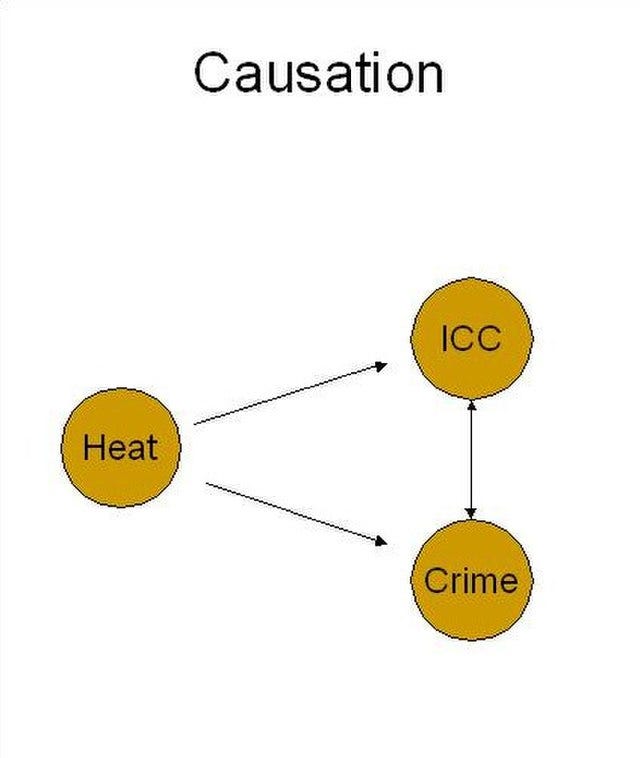

The picture above shows a famous example from the crime literature. Violent crime, in particular, goes up when the temperature does the same. So does ice-cream consumption. Hence ice-cream consumption correlates with violent crime, even though there is no causal relationship between the two.

One more point: it all depends what kind of crime you’re thinking of. Poverty and crime are often pictured as belonging together – cohabiting, even - but a moment’s thought shows us that certain kinds of crime are a consequence not so much of poverty but of its opposite. Think of insider trading, for instance, or industrial spying, vote-rigging, and most kinds of bribery. Think of industries that regularly flout health-and-safety laws or pollution guidelines. Think of the international cocaine trade. White-collar crime depends virtually by definition on affluence. Poverty doesn’t cause that kind of crime.

Let’s say we agree that certain kinds of crime do go together with poverty. Plenty of other phenomena do, too. One example is a lack of educational opportunity. Perhaps that is the cause of crime, rather than the poverty itself. There are other examples, too, such as low-quality diet. Perhaps that’s the cause. Or both. Or neither. Or only when people live in old, low-quality housing. Or any number of other things.

Does ‘poverty cause crime’? Very possibly, depending on what exactly you mean. I’m not going to argue otherwise. Do we know that? No, we don’t.

One more thing before we part: If you like my work, or anything about what I’m doing here, please consider a Pledge. This Substack is free, and will remain so for a long time yet, but a Pledge right now would guarantee you access to it even if that changes. A $60 Pledge would work out at just $5 per month, and I can’t tell you what a boost it gives me when my kind readers tell me that the work I do is worth paying, even just a little bit, for. Thank you!

Pictures courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

References added partly out of academic habit; partly so that you can chase up anything you found particularly interesting.

[i] Heiman, Gary W - Understanding Research Methods & Statistics: An integrated introduction for Psychology, Second edition, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 2001, pp. 2-28

[ii] Almost only ever. Accidents do happen, sometimes good ones.

[iii] No wonder kids were taking to violence. They were bored out of their heads.

[iv] Bandura A, Ross D & Ross SA – ‘Imitation of film-mediated aggressive models’, Journal of Abnormal & Social Psychology, vol 66(1), pp3-11

[v] Brace, Nicola – ‘Measuring & manipulating variables’ in Jean McAvoy & Nicola Brace (eds): Investigating Methods, Open University, Milton Keynes, 2017, pp83-122

As a human being who has always been fascinated by the existence (that can be read as fascination with the causes) of crime, I started out in college as a psychology major. That was in a Skinnerian department in the early 1960s and my weakness in math persuaded me to try political science and then journalism instead. That has a good deal to do with my reaction to the post. Psychology does deal with causes and my career as a reporter causes me to say that even before you can ask about causes of, say, a murder, you have to ask what really happened.

The longer I have chased and compiled facts about crimes, the more I have come to understand that there are almost always vast differences among eyewitnesses, cops, prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges and reporters about what truly took place in a situation. People misunderstand, they articulate poorly or they simply lie. So the facts of an event get garbled from the outset. They may not even be facts at all. And establishing solid, reliable pieces of evidence is a skill that is being lost, certainly in the field of journalism.

Jason's discussion isn't rendered useless by my observation, not at all. He is a serious student of all the elements that go to make up human behavior. My observation is only a reminder that the world we live in is full of forces that distort our perceptions of who really hit Harry and with what intent. Modernists and deconstructionist have given license to disregard "facts" because they are merely tools of the powerful to oppress the powerless. Until we find a way to judge and verify evidence, we're going spend a good deal of time thrashing around, looking for causation and meaning.

And thanks, Jason, for indexing your work, making it more accessible. The world is awash with information and opinion. Substack adds to that volume every day. I regularly read a dozen essays and post, and then, the next day, can't remember where I saw that "fact" I remember. Often as not I merely want to steal it but at least I try to credit it to its originator.

Thank you very much indeed for the cross-post! It was very kind of you. I hope your readers enjoy the article.