POLICE VANS: WHY DO DRIVERS KEEP CRASHING INTO THE BACK OF THEM?

Road accidents; policing; injury; visual perception; attention; LBFS

Below you’ll find a picture that I took recently, not too far from where I live. Can you spot the police van? Pretty visible, isn’t it? At least (you might say) it looks pretty visible. It looks as though you’d see it easily enough. But not everyone does.

Police vans (indeed, emergency vehicles of all kinds) are designed that way. They have flashing lights, reflective devices, retro-reflective devices. Those big red stripes aren’t there by accident. They’re there, in fact, to prevent accidents. They’re supposed to stop you from driving accidentally into the back of the van. What could be bigger, clearer, or brighter? Police vans, to use the jargon, possess high ‘sensory conspicuity’, meaning that they have certain qualities that ought to be picked up easily by our senses.[i]

‘Ought to be’ is the important phrase there. One of the highway’s many surprises: the number of drivers who crash straight into the back. It happens most often when vans are parked on the hard shoulder of a motorway or otherwise blocking off a lane of traffic. When asked about the accident, drivers say something surprising. Even though they were honestly and genuinely paying attention to everything around them, they simply did not see the van until it was too late. Big red stripes, flashing lights, retro-reflections, even strings of traffic cones... Sensory conspicuity didn’t have what it takes to make the van conspicuous. The drivers just didn’t see them.

It’s not just police vans, either. Accidents of this sort ‘account for a large proportion of all crashes’[ii]. A ‘large proportion’ indeed: according to one Australian study, it could be anything up to 80%.[iii]

Psychologists have a special name: Looked But Failed to See (or LBFS). LBFS accidents happen most commonly at junctions, where drivers pull to a stop and, you’d think, look around to check whether it’s safe. Motorcyclists and bicycle-riders are in special danger.

Of course, motorcycles and bicycles have far less ‘sensory conspicuity’ than regular cars, or police vans. They’re harder to see, because, for one thing, they’re a lot smaller. A lot of early research assumed that drivers simply failed to detect them.[iv] That’s why police vehicles were redesigned to become so garish and, you’d think, impossible to miss.

This is, of course, common-sense psychology. Drivers fail to see an object? Make the object bigger and brighter!

It turns out, though, that straightforward visibility isn’t the problem – at least not the whole problem. There are at least two other matters to consider, one more intuitive than the other.

First come ‘failures of vigilance’. Drivers sometimes, with the best will in the world, get distracted for a moment. Perhaps their phone rings, perhaps an animal dashes past, perhaps there is a particularly alluring billboard. Next thing you know, they’re smacking straight into the side of a motorcycle or the back of a police vehicle.

Second – much more interesting – come ‘false hypotheses’. They prey on very particular kinds of driver…

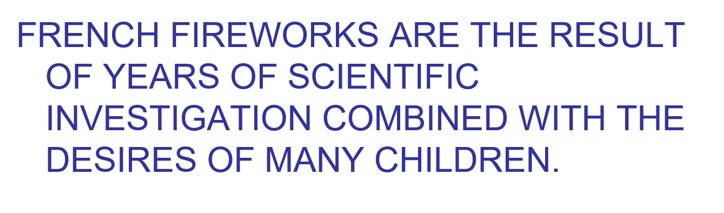

You’ll see what I mean if you try this very simple exercise. Read the sentence below, quickly, and then read it a second time, counting the letter ‘F’ whenever you see it. How many ‘Fs’ are there?

Now, I don’t know what answer you came up with (you didn’t cheat, did you?) but if I were a betting man, I’d bet three. If that’s what you got, try again.

Did you get the same answer the second time? The correct answer is six. Don’t believe me? Try again, this time paying attention to the word ‘OF’. I bet you skipped it the first time you read that sentence. In fact, I bet you skipped it the third time.

Of course, you may have got the answer right, in which case good on you. But chances are you didn’t. Chances are you got three. The reason is as simple as it is counter-intuitive. As a regular, devoted Substacker, you are a highly-skilled reader. You’ve read the word OF hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of times in your life. You don’t need to look at ut to know it’s there. In fact, I bet you didn’t even notice that I misspelt the word ‘it’ in the last sentence.

If some psychologist were to scan the movement of your eyes as you read that sentence, they would probably discover that you had not even fixated on the word. Why would you? Processing it is a waste of precious mental resources. You only have so many resources (like everyone else on the planet, you are a ‘limited capacity processor’), so why waste them on a task, however trivial, that you can do anyway?

In skilled readers, we say that reading has become an ‘automatic process’. You read familiar words without expending any mental energy at all.

That makes sense when you think about tasks like, say, doing up shoelaces or brushing your teeth. Through repetition, they have become automatic, too, freeing up precious mental resources for more complex tasks like processing an article on LBFS accidents.

The advantages are obvious. Sadly, you don’t get anything for free in this life. Automatic processes come with a built-in disadvantage: a big one. Undoing one is like unmixing a cocktail. Have you ever planned a drive to the shops and ended up at work instead? You can admit it, it’s all right. Lots of people have. The drive to work is automatic. You do it without thought. In fact, the more experienced and accomplished a driver you are, the more likely you are to have done something of the sort. It’s not stupidity, as you may have been tempted to suspect. It’s expertise.

MORE FROM CRIME & PSYCHOLOGY:

Cousin marriage & why it’s a bad idea

Learners are practically immune. When they’re behind the wheel, they have to think about everything they do. In other words, they have to expend mental resources on tasks that you, skilled driver, do not.

You’d do the task with the ‘Fs’ better if it was in a language you did not know.

How does this bear on the whole ‘police-van’ phenomenon? When psychologists looked into it, they found that LBFS accidents did not happen randomly, or even unpredictably. Here’s what they have in common:

Accidents tended to happen when the police van was parked ‘in line’, meaning that it was facing in the same direction as traffic, with the back of the van facing the driver behind.

About two-thirds of the accidents occurred within 15km of the drivers’ homes.

Novice drivers were hugely under-represented. In fact, LBFS accidents happened almost exclusively to drivers over the age of 25, with years of experience.[v]

Perhaps we can see why. Driving on a motorway or dual carriageway is a task with which certain drivers are very familiar. It will be particularly familiar to drivers with a degree of expertise – they have been doing this for years and years – and, anyway, they’re not far from home. They may know the route as well as they know their own house. Much of their processing is therefore automatic. They do not expect to see a stationary vehicle in one of the lanes and so, at first, their sensory system doesn’t even register it.

Not only that, but, for experienced drivers, the back of a vehicle ahead of them indicates one thing: the vehicle is moving. If they perceive it at all, they assume that the vehicle is moving away from them at approximately the same speed they are moving towards it. Experience tells them so.

Drivers with less experience and those who are on an unfamiliar road, paradoxically, are least prone to LBFS accidents. They are not on automatic pilot, which means they are actually paying the kind of attention to the road that your driving instructor used nag you about.

Crashing into a police van is bad enough, but it could be worse. Imagine the situation with airline pilots. In one notorious experiment, a groups of them were asked to operate a flight simulator in which flight console information was projected directly onto the cockpit windshield. The hope was to decrease the number of errors they made, since they could see their console at the same time as the outside world. Four out of nine experienced pilots attempted to land their plane even when another plane was parked on the runway.[vi]

When queried afterward, these pilots said they never saw the other plane at all. They were experts. They’d done this over and over again. There had never been a plane on the runway before, so there could not be one now. Expertise can be deadly.

You know what else is deadly? Missing out on your weekly does of Crime & Psychology! Reserve your copy now by banging a big blue button below.

If you think my hard work here at Crime & Psychology might deserve a coffee – go on, you know it does! - if you’d like to you can buy me one here.

[i] Langham, M, Hole, G, Edwards, J, & O’Neil, C (2002): An analysis of “looked but failed to see” accidents involving parked police vehicles, Ergonomics, 45(3), 167–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140130110115363

[ii] Langham, M & McDonald, N (2007): ‘Crikey! It’s cognitively complex’, in: IJ Faulks, M Regan, M Stevenson, J Brown, A Porter & JD Irwin (eds), Distracted driving. Australasian College of Road Safety, Sydney, NSW, pp 345-377. Emphasis added.

[iii] Cairney, P & Catchpole, J (1995): ‘Patterns of perceptual failure at intersections of arterial roads and local streets’, in Gale, AG (ed.), Vision in Vehicles, VI, Elsevier Science, Amsterdam

[iv] Edgar, Graham: ‘Perception & attention’, in Dorothy Meill, Ann Phoenix & Kerry Thomas (eds), Mapping Psychology, Milton Keynes, UK, 2007, pp1-51

[v] Langham, M., Hole, G., Edwards, J., & O’Neil, C (1998): Can the ‘Looked But Failed to See’ Error Involve Highly Conspicuous Police Patrol Cars? Evidence from Accident Reports & Laboratory Studies, First Engineering Psychology Conference, BPS Special Interest Group, University of Southampton

[vi] Haines, R F. (1991): ‘A breakdown in simultaneous information processing’, in G Obrecht & LW Stark (eds), Presbyopia research: From molecular biology to visual adaptation, pp. 171–175, Plenum, New York

People don’t pay attention at all, which is terrifying. I worked in auto insurance for 17 years and every day, people would say that the other car “came out of nowhere.” It sounded like everyone lived in a strange dimension with all these cars suddenly appearing out of nowhere.

It’s terrifying to think of planes hitting other planes.

Another fascinating subject. Have you seen the clip with the gorilla that people don’t see? As I type this, I’m worried that you mentioned this clip in your article and I read it but didn’t see it.