Sunday e-mail 9th February: The science of detection

Clue-puzzles & whodunnits; what scientists do; fiction & reality

Have you read our article from a few weeks ago, about Batman and the Joker? It recently took the prize as the least popular article on the Crime & Psychology Substack. I feel sad about that because it may be my favourite. Never fear, you don’t need to be a comics nerd to read it. Everyone’s invited. If you don’t agree it’s worth a few minutes of your time, I’ll give you your money back.

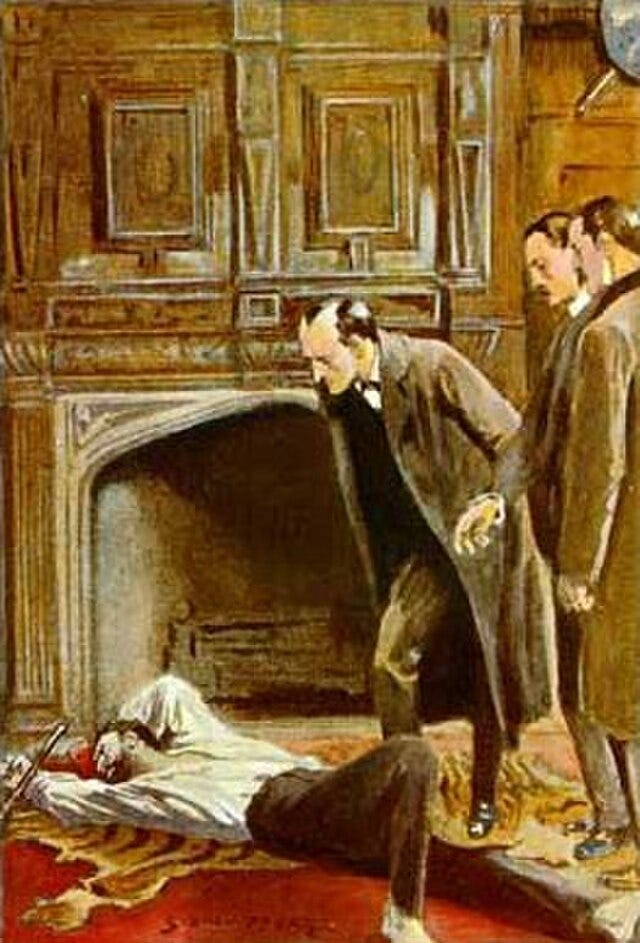

Speaking of the World’s Greatest Detective… The genre of crime fiction known as the clue-puzzle appeared a little over a century ago. It put brainy detectives front and centre, ones who devoted their lives to nothing less than the continual restoration of order. Dorothy L Sayers and Agatha Christie inhabited a civilisation that had seen a world-wide breakdown on a scale unimagined in history. Certainties had been not so much swept away as exploded. Society seemed as anarchistic as the physical universe must have seemed in the days before Isaac Newton sat under his apple tree. Fictional detectives accordingly set about a great task of rectification, of tidying-up. If they could not reverse time and have the victim somehow unmurdered, they could at least make sure the guilty were appropriately chastised and good manners prevailed.

The process they employed – no matter what Sherlock Holmes insisted – was not one of deduction but induction. Induction means reaching conclusions – forming theories – on the basis of evidence. That’s how you solve crimes, or at least how you’re meant to. Deduction, on the other hand, means deriving data on the basis of theories one has already constructed. In the world of law-enforcement, deduction therefore means fitting up a suspect you’ve already chosen. That’s frowned upon.

One major – often the major – source of legal evidence comes from interviews with suspects and witnesses. That is where the clue-puzzle detective gets those clues. Interviews are to the detective what experiments are to the scientist. They provide data and - properly collated by an expert such as Miss Marple or Lord Peter Wimsey - data leads to theory: which is to say that it points at suspects.

The detective shares with the scientist a particular philosophy (what other writers, less allergic than I am to posh vocabulary, call an epistemology). They believe not only that clues point towards the right answer, but that there is such a thing as a ‘right’ answer. They believe, in other words, that it makes sense to talk about ‘truth’ (whether scientific or legal) that exists, out there in the world, and which one might, with enough skill and acumen, manage to discover. Some philosophers prefer to write that last word as ‘dis-cover’, but those people are not half as clever as they think they are.

Most scientists share a philosophy called ‘scientific realism’. That daunting phrase means only what Fox Mulder used to mean in The X-Files: ‘The truth is out there’. To search for it is as meaningful in science as it is in policing.

Recent decades have seen endless attacks on scientific realism. Public faith in ‘truth’ has experienced a world-wide breakdown on a scale unimagined in history. Many an academic will tell you with a straight face that ‘there is no such thing as truth’. To search for it is meaningless. Science may impress only because the scientific ‘narrative’ tends to be ‘privileged’ over other ‘narratives’ that are equally valid.

When such a view spreads to policing…well, that’s when everyone becomes a suspect. That’s when no one’s narrative is privileged over anyone else’s. That’s when police can pick and choose which crimes to investigate, or not. That’s when crime journalists start to treat the criminal as a victim and vice versa. That’s when we get conspiracy theories, victim-blaming, and deep-sea levels of trust in our justice systems.

Witnesses in court swear to tell ‘the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth’. In a world in which the very concept of an objective ‘truth’ has started to wear the scare-quotes that I just added, it can’t be long, surely, before they are instructed to tell ‘my truth, my whole truth, and nothing but my truth’. Whether it’s true or not.

There are signs that the clue-puzzle is coming back into vogue. Avid for a little certainty in this chaotic world, distressed readers are making Richard Osman one of the bestselling authors in the language. Everyone wants to believe in something, even if that ‘something’ is fiction.

Wednesday’s newsletter is all about clue-gathering. I hope you enjoy this piece on the forensic psychology behind an important police interview technique – one that allows police officers to discover the truth behind a crime.

I’ll see you on Wednesday, Crime & Psychology fan! Until then, please enjoy banging the blue buttons below:

Here are five quotes about truth and the psychology behind them:

· ‘Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.’ This well-known maxim about truth comes from a fictional character, although we can credit his creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. When he wrote it, he was clearly thinking about the scientific method. Science, as we lecturers never tire of telling our students, proceeds by disproof, which is another way of saying that we are constantly eliminating the impossible. (I’m lying. We lecturers always tire of telling our students that.)

· ‘The truth will set you free, but first it will make you miserable’, said James Garfield, who had in mind, doubtless, all the Psychology research indicating that, rather than unrealistically negative mindsets, people with depression actually have an impressively realistic ability to weigh up the good and the not-so-good in life.

· ‘We live in a fantasy world, a world of illusion. The great task in life is to find reality.’ So wrote Iris Murdoch, philosopher and novelist. Scientific realist, too, it appears.

· ‘Even if you are a minority of one, the truth is the truth.’ Mahatma Gandhi was probably thinking about Social Psychology experiments on group influence carried out by Solomon Asch, or those on minority group influence by Serge Moscovici.

· ‘A lie can travel halfway around the world before the truth can get its boots on.’ This quote is often incorrectly attributed to Mark Twain. In any case, it builds on sayings that were current long before his time. If you’d like to read about the quote’s history, check this out. Alternatively, just wait a few weeks and we’ll have a lovely piece of the psychology of conspiracy theories.

Both images courtesy of WikiMedia Commons.

I am a big fan of the Sherlock Holmes novels. Even as a modern scientist or criminalist one can find a lot of great ideas and wisdom in them (and also a lot of rubbish, of course). Thanks for pointing out that the frequent usage of the word 'deduction' in the novels is inaccurate at times. I just want to add that Holmes uses a variety of logical arguments, of which some are in fact deductions, others inductions, and some abductions. Some would argue that the latter (abduction: inference to the best explanation) is the most important in Holmes logical reasoning. Umberto Eco (and a few others) wrote a book about that specific topic. Thanks for making Holmes a topic on your blog; I think that these novels still have a lot to offer.

Thank you for covering the ground on induction and deduction, these are confusing terms to many of us I think. Probably because they were pretty weirdly chosen and hint at the opposite of what they are. Deduce sounds like coming at something from a set of facts and induction is like you get in there by intuition, instinct and hypothesis. Probably best to not try to fit the terms into etymology as this may very likely cause upset and regret.

It was lovely to have Gandhi back, he sounds spot on as regards the issues of the day. Will you be going over motive and opportunity in the next pieces? And in real life do we think methods of solving crime can be divided neatly into deduction and induction? After all I might accuse you of working to find circumstances specifically demonstrating that the husband killed his wife, ie working from a hypothesis and not a know fact. But then you could argue you're simply working from the known fact that most murderers are close family members and partners. I can see it would take some scones and builder tea to sort that out. Thank you again and keep up the good work.