JURIES AND JURY DECISION-MAKING

Everything you need to know about what goes on in the jury room

Do you remember our last newsletter, Crime & Psychology fan? It was a trip through time and space during which you had to imagine yourself taking part in a jury trial, your fate and freedom in the hands of the strangers in the jury box. I explained the so-called Story Model, which is one account of how individual jurors reach their decision during the first stage of deliberations – that is, while the lawyers are presenting their arguments in court. The jurors’ choice of story seemed to be influenced by various ‘certainty principles’.

If you missed the newsletter, there’s no need to hang your head or feel ashamed. Please don’t. Just click here and it will be as if you were with us all along… Have you read it? Are you back? We’re glad to see you again. Now you can read the next paragraph.

The evidence once heard, jurors must retire and discuss their verdict. In the jury room, they have to take the raw materials of their initial, individual, decisions, and use them to produce a unanimous - or at least majority - verdict (depending on the jurisdiction). They must present a single agreed decision to the judge. Another way of saying this is that the jurors turn into a jury. Juries have their own decision-making processes, distinct from those of jurors.

Inside the jury room, the psychology of the individual may become less important than the psychology of the group. Cognitive Psychology may give way to Social Psychology as social dynamics get to work.

Let’s take a look at some of these social dynamics and see what psychologists have learnt about them.

Your jury may turn out to be less than the sum of its individual parts. Groups often work that way. Point it out to your line-manager next time they call another one of those pointless damn meetings. (Actually, I did. Made no difference.) That’s because of a psychological phenomenon called social loafing. ‘I’m in a group,’ some of your jurors are likely to think. ‘No one will notice or even care if I don’t pull my own weight. Someone else will pull it for me’.

(God bless the employees who think that way. If everyone did the same, the world would surely be a better place, because there would be far fewer meetings.)

Social loafing has been on psychologists’ maps since 1913, when a fellow named Ringelmann for some reason decided to see how much force eight individual people could exert in a tug-of-war. He compared their individual output with their output as a group[i]. Naïvely, we might expect the second measure to be a straightforward addition of the eight earlier ones, but no. It was about half. Once they were in a group, people worked, on average, with just 50% efficiency.

If you happen to have a trial date approaching, perhaps this will make you feel concerned. Members of the jury may simply not try very hard, or put in a great deal of effort, to reach the correct decision.

Perhaps you’ll be comforted, though, if your jury, through some trick of fate, happens to be composed entirely of women, or people from collectivist cultures. Compared to male westerners, it seems that both demographics place more emphasis on participating in group activities like jury decision-making[ii].

You might also take comfort in the opposite of social loafing. The jargon term is social facilitation. There are certain circumstances that actually lead people to work harder when they are in a group. The task has to be important (such as deciding another person’s fate) and there must be reason to believe that other group members will loaf. If so, your luck may be in.

Groupthink is a term I’m sure you’ve heard. It is one of those terms – like ‘anal retentive’ or ‘short-term memory’ – that have leaked out of academic Psychology into everyday life. No surprise there, since groupthink is no rarity in the workplace. It happens whenever members of a group favour cohesiveness over correctness. To phrase it another way, they avoid dissent even if that means being wrong.

It isn’t difficult to predict the conditions that lead to groupthink. They include a stressful context, high stakes, a group of like-minded people, a powerful leader who lets their own opinion be known, and isolation from other groups who might have different opinions. If this makes you think of cults, political quangos, and drug-rehabilitation centres, well, you’re spot on.

Those exact conditions were in place in 1961, when President Kennedy ordered that well-known fiasco, the Bay of Pigs invasion. It was a badly-planned and poorly-executed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro’s Communist regime in Cuba. Indeed, so badly planned and so poorly executed was it, some historians have argued that the CIA actually set Kennedy up to fail[iii]. We shan’t get into that right now. The important point is that there were Goldilocks conditions for groupthink: ‘the overthrow of one of America’s arch enemies was at stake, Kennedy’s group of advisers were like-minded regarding the invasion and met in secret, and Kennedy was a forceful and charismatic leader who made his intentions to invade Cuba known to the group’[iv]. It was a study of these conditions that led the psychologist Irving Janis introduce an idea that has seen his name included in just about every introductory Psychology textbook in the language.

There are five symptoms. If you happen to belong to any group that exhibits them, it’s time to resign. If that group happens to be a jury, well, you can’t. You’ll have to fight the good fight. And if, instead of being a jury-member, you happen to be the accused, well, you’ll never know exactly what happened in the jury room, but let’s hope it wasn’t this:

First, the group is convinced of its own moral rectitude. In its own eyes, it can do no wrong. No doubt you know people who have this trait. Self-righteousness is frightening enough in an individual: Just imagine how much more dangerous it is when an entire group is involved.

Second, there is little or no dissent from the views held by the group leader (in our case, the jury foreperson). The group is not a democracy so much as an autocracy.

Third, once the decision has been reached, the group refuses any critique. Instead it rationalises and ratifies. In the case of, say, a Guilty verdict, that means twelve people reassuring each other about how noble, correct, and courageous they all are and how much you, the defendant, deserve your punishment. There’s little chance that such a jury will even recognise, let alone rectify, its own mistakes.

Fourth, no member of the group will listen to any point of view they do not already agree with. Dissenting jurors may be ignored (or, in modern jargon, deplatformed).

The final symptom has the coolest terminology. The group has its own ‘mindguards’. They are group-members who prevent insurgency by ensuring that no turncoat, malcontent, or apostate starts to entertain unwanted thoughts. They push the party line. The party line is groupthink.

A less cool term is group remembering. It comes next on our list of processes that influence juries. Give a random individual a general knowledge test and compare their score with that of a randomly-generated group. Chances are the group’s score will be higher. That’s only to be expected, since group members will be able to pool their knowledge. If one person doesn’t know, say, the capital of Australia[v], another will be likely to. But give them a more difficult task, such as remembering the complex details of a court case, and the numbers may be reversed.

That’s because a group produces a shared, and sometimes compromised, reconstruction of the material in question. Some group members contribute a great deal (yeah, you know the type). Others may contribute nothing. Perhaps they are bored, apathetic, shy, or just don’t happen to like being in a group. Reconstructed material may nor may not be accurate. This is another way of saying that consensus, again, may take precedence over truth.

The third process is group polarisation. This is when groups make decisions that are more extreme than the individuals would make on their own.

That’s a difficult idea to digest at first, so allow me to give you an example. Say we have a jury with twelve members. All of them think the defendant is guilty and should serve time in prison. Now imagine we poll each individual jury-member and ask them how long the sentence should be. The individuals’ answers will vary, of course, because they will have slightly different opinions from each other, but let’s suppose the average is five years. We ask the jury to discuss the case as a group and agree among themselves on the appropriate sentence. They may well decide that, instead of five, it should be eight years, or ten. That’s group polarisation in action.

Not what you’d expect, is it? Most of us anticipate that groups will tend to make less radical, more average, decisions than individuals on their own. We tend to think of committees, for example, as being prey to the horrors of compromise and special interests (remember that joke about a camel being ‘a horse designed by a committee’).

When all the individual members of a group start off by leaning in one direction rather than another, though, we often find that their discussion simply serves to make their views more extreme. If they started out leaning towards the riskier strategy, the group decision becomes riskier (the ‘risky shift’). If they lean towards caution, we sometimes get the opposite (the ‘cautious shift’).

This is consistent with the finding that, for 90% of juries that reach a decision, it is in the direction of the initial, pre-deliberation majority[vi]. Don’t expect too many Twelve Angry Men outcomes in real-life juries.

Why should this happen? There are numerous possibilities. First, ‘social comparison’. The idea is that that group members (jurors) compare themselves with their colleagues and try to match or outdo their attitudes. That’s because extreme positions are sometimes associated with high status. Adopting such a position, then, may promote you from a beta to an alpha. That’s hardly a reassuring thought for the innocent defendant, who’s surely hoping the jury will reach a rational decision based on nothing but the evidence.

Sometimes, jurors’ assessment of each others’ attitudes may be influenced by a bias known as ‘pluralistic ignorance’. Imagine that a significant number of jurors mistakenly assume that the other jurors think the defendant is guilty. Publicly, they may pretend to agree, even though privately they do not. People hate to be the odd one out[vii]. Conformity is a powerful psychological process. If you’d like to read more about it, you could look at this newsletter.

The unhappy result may be that, while most of the jurors do not actually support the Guilty verdict, the defendant gets sentenced to prison anyway.

Finally, a jury of twelve will naturally tend to come up with more ideas than one individual juror alone. Jury-room discussions will therefore bring to light new information that many jurors haven’t thought of previously. If the jurors were initially leaning towards a Guilty verdict, most of this new information will tend to support that verdict. Psychologists call this phenomenon ‘informational influence’.

Batter the blue buttons, Crime & Psychology fan! It costs you nothing but it does help to keep these newsletters going.

Or think about maybe buying me a coffee! That’d be nice.

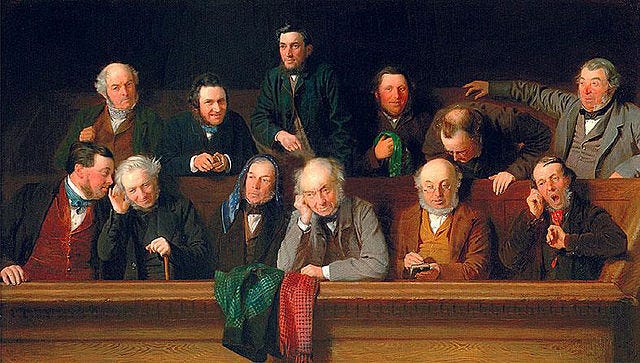

The painting is "The Jury" by John Morgan, 1861. Reproduced courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Ringelmann, M, cited in Martin G Neil, Carlson Neil R & Buskist William: Psychology – 4th edition, Allyn & Bacon, Harlow, England, 2010

[ii] Karau SJ & Williams JD: ‘Social loafing – research findings, implications, & future directions, Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4,134-9

[iii] Talbot, David: The Devil’s Chessboard – Allen Dulles, the CIA, and the rise of America’s secret government, William Collins, London, 2016, pp393-412

[iv] Martin G Neil, Carlson Neil R & Buskist William, op cit, p695

[v] I use this example in class a lot. It’s Canberra, not Sydney.

[vi] Kalven H, Jr & Zeisel H: The American Jury, 1966, Boston, Little, Borwn

[vii] Abrams D, Wetherell M, Cochrane S, Hogg MA, & Turner J: Knowing what to think by knowing who you are- - self-categorisation & the nature of norm formation, conformity & group polarisation, British Journal of Social Psychology, 29, 1990, pp97-119

This is fascinating. I've read recommendations that we do away with jury trials for things like sex offenses (specifically rape) in favor of only a judge-trial, with a judge who is well-informed on many of the nuances of rape, psychological responses and effects upon victims, and the like. Part of the argument is based on the pitfalls of group decision-making such as what you outlined here.