The New York Times used to run a feature called ‘The Stone’, which featured a different essay on Philosophy every time. When the essays were collected into The Stone Reader, there was a fascinating cluster on on free will. Two essays in particular inspired me to write this newsletter: ‘Your Move - The maze of free will’ by Galen Strawson and ‘Experiments in Philosophy’ by Joshua Knobe. Together they provide a colourful map of treacherous terrain. There’s no avoiding it: the road to Criminal Psychology passes directly through the middle. The going may look smooth and easy from a distance, but just wait till we get down there… Don’t worry. This trip is going to be fun.

Here's the situation: Imagine you are a former law student who has an idea for a novel. If you get the opportunity to write it, your novel will be a great gift to humankind (on the level of, say, Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment). For sure, it will be one of the most important works of literature ever created. One thing and one thing only prevents you from writing it: extraordinary poverty. A local pawnbroker, you believe, has hordes of cash secreted around her shop, sufficient to buy limitless time and gallons of ink. Not only that, but - you have convinced yourself - the pawnbroker is venal and wicked. Her existence is as much a burden to humankind as your novel would be a gift. On a visit to this pawnbroker – perhaps to pawn an old watch for a stingy handful of change – you spy an axe in the corner. The axe just standing there, tempting you, the way they do. The choice that confronts you is clear.[i]

Now, you, of course, are an upstanding exemplar of morality (you have proven as much by subscribing to Crime & Psychology). As such, you would take the high road. You would pawn the watch, take your change, and buy yourself a little time alone with a sheet of paper. You would do so even though you could be certain that this particular sheet of paper would remain as clean as a field of new-fallen snow. As clean as your conscience, in fact. The pawnbroker lives but your novel dies.

Every decision we make forces us further into what the short-story writer Jorge Luis Borges used to call the ‘garden of forking paths’. In the example above, you took the noble path. Good for you. In the same situation, though, you can be sure that some wannabe novelists would do otherwise. We agree, I expect, that they should be punished for the wickedness of their choice.

Can you imagine any legal system that would decline to punish them? Probably not. That’s because legal systems are designed to punish those who freely and wilfully choose to commit crime – in other words, those who do it of their own free will. Remove the notion of free will and their responsibility for the crime seems to dissipate like smoke from a gun. In the absence of free will, it’s difficult to justify punishing anyone.

Yet the phrase about ‘taking’ a path is loaded. It implies the kind of conscious decision-making that some psychologists doubt really exists. Perhaps you had no choice which path you went down. Perhaps you did not so much take the path as were taken down it.

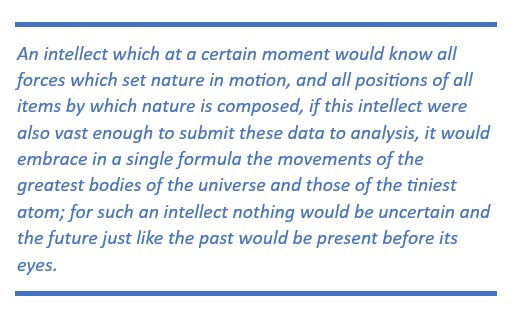

Speculations like these point towards a phenomenon known as determinism. It’s a philosophical position that became popular during the nineteenth century, when many smart people believed that science might be equipped to solve any and all of our human problems. The most famous statement of determinism was made by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1814:

Everything that happens is part of a causal chain. That includes complex human behaviour like committing violent crime and justifying it to oneself as part of the plan to write a great novel. Today’s scientists more or less take the idea for granted. In fact, the fundamental methodology in science – the laboratory experiment – is designed precisely to establish cause-and-effect relationships of the sort that fit into such a causal chain. It has developed since his time, for sure, but Laplace would have recognised the idea.

The implications for our subject are troubling, to say the least. If a criminal’s actions are the effect of some recognisable, discoverable cause, the concept of free will starts to look vapid. It becomes unclear, in other words, that you freely chose to ignore the axe, however much you felt as if you did. Perhaps more troubling, it is unclear that the criminal who found himself in the same situation freely chose to use it. How is the law to justify punishing a murderer who is simply trapped in a causal chain? We do not punish people for doing things they could not help doing, after all, and our criminal, it seems, could not help using the axe.

Do we even want to conduct scientific research into free will if the results might not go our way? Such results would call into question the whole basis of our legal system. That can’t be good.

What I have said so far may seem counter-intuitive. Let’s be clear about this: I am not denying that you feel as if you are free to choose. For the sake of argument, let’s say the whole regrettable affair with the pawnbroker and the axe occurred yesterday, Tuesday. Looking back on it from the vantage-point of today, Wednesday, you will certainly be able to convince yourself that things could not have turned out differently. The choices you made were the only ones you could possibly have made. (Think of it this way: The pawnbroker is alive today, Wednesday. How, then, could it possibly be the case that, yesterday, Tuesday, you had the option to use the axe? There is no conceivable universe in which that could have happened.) Even so, at the time you made the decision, you were surely convinced that you – law-abiding Crime & Psychology reader that you are - did freely choose not to become a murderer. ‘Murderer’ is not an identity to be assumed lightly, after all, and really ought to have involved a considerable amount of thought.

It is possible that the illusion of choice just that – an illusion? Perhaps your mind was simply playing tricks on you. There’s plenty of evidence that it does so all the time. Neuroscientists, after all, have known for decades that our apparently conscious decision to perform such a trivial action as flicking the wrist comes long after the brain signal telling the wrist to move (technically called the ‘readiness potential’) has come and gone. Here is another way of saying the same thing: by the time we are aware of our intention to flick our wrist, it’s already too late to back out. Not just too late, in fact, but way too late. The readiness potential precedes conscious intention, on average, by more than one-third of a second. You may be under the subjective impression that you made the decision with conscious intent, but that impression, some neuroscientists claim, is entirely artificial. The decision was made long before.

This is a tricky business, all right. Our criminal’s ‘conscious intention’ to use the axe is an ethereal, intangible thing. It’s unclear that something of that nature could possibly interact with the solid stuff of the criminal’s body. It’s not clear that something like a ‘conscious intention’ – something utterly lacking in substance - could be responsible for moving the criminal’s (very material) feet towards the place where the axe is waiting, making his hands grasp the shaft, making his arms lift it, making his hips swing… Clearly, some neuroscientists argue, the ‘conscious intention’ that the criminal undoubtedly feels really and truly does deserve its quotation-marks. It’s no more than a by-product of material processes that are happening in the brain (the technical word is ‘epiphenomenon’).

To take over a person’s will, the neurosurgeon Itzhak Fried discovered, can mean nothing more than passing an electrical current through certain regions of their brain. Fried, in fact, discovered that if we monitor just 256 of the brain’s numberless neurones, we can predict a person’s decision to move, with 80% accuracy, 700 milliseconds before they themselves know anything about it.[ii] Others have discovered that the brain-states that precede decision-making exist in the brain up to 10 seconds before a person becomes aware of having made any decision at all.[iii] Findings like that can effectively make people look like puppets dangling from strings made of their own neural pathways.

Let’s imagine for a moment that the illusion of choice really is no more than an illusion. We can see why it might be a handy one, why evolution might have selected for it. The psychologist, Roy Baumeister, discovered that a strong belief in free will tends to go together with pro-social behaviour – the kind we like think of as ‘morally good’. Examples are gratitude and the restraint of aggression. An evolved sense of free will, then, tends to lead to social harmony.[iv] That’s got to be worth something.

Psychologists know that people can easily be manipulated into thinking a certain decision was their own, even when the situation has been engineered to ensure they have nothing to do with it. Professional magicians and conjurors know the same thing. The reverse is true, too. Psychologists have known for decades what makes the glass spell out words on a Ouija board or the table spin and move across the room during a spiritualist meeting. We call it the ‘ideomotor effect’. Its origins are in the unconscious movements of the people at the séance or the meeting. The medium’s big trick is to prevent them from recognising that those movements began in their own bodies.

In fact, it’s difficult to see how your apparent free will could possibly be anything but an illusion. You choose, or do not choose, to pick up the axe. Conceive of this action (or non-action) as a single link in a long causal chain: ‘just one thing causing the next, which causes the next’.[v] When it comes to human behaviour, psychologists conceive of links forged from genes, or socialisation, or both (this is what we mean by ‘nature and nurture’). If you can hardly be held responsible for the chain’s previous links, you can hardly be held responsible for the ones that are yet to come. The effect can hardly be your responsibility if the cause was not. It would be a strange legal system indeed that held you responsible for the genes you inherited from your parents, or the rules your caregivers taught you when you were a child.

Not responsible for either nature or nurture, you surely cannot be held responsible for whatever consequences spring from them. Unfortunately, you don’t get to take credit, either, for not becoming a murderer. You just don’t become one, and that’s all there is to it.

This is a really big problem for Psychology, but one that few psychologists like to think about. Do you know why they don’t like to think about it? Because it’s a really big problem.

There is a familiar response to conundrums like this. You may be feeling it yourself right now. Part of you wants to go along with what appears to be the rational, scientific view, and say, no, of course we don’t have free will. It’s obvious! Another part responds emotionally – of course we do have free will! It’s obvious!

OK, you may say. I agree that when the shadowy criminal killed the pawnbroker, that was just one link in a chain of causes, none of which was the shadowy criminal’s responsibility. But the shadowy criminal could perfectly well decide - as you yourself once did– to be good and obey the law of the land from this day forward. He failed to do so and we should punish him for that, right?

Agreed, the criminal could make that decision, but where would the decision come from? To make a decision, after all, is a kind of behaviour, and we have already agreed that behaviour is always the effect of some pre-existing cause. Should the criminal choose to become law-abiding, all well and good – but that decision can represent nothing more than the next link in the chain. Once more, he deserves no credit for something he could not possibly have controlled.

In order to make the choice at all, the criminal must have the ability to do so. And where did that ability come from? Presumably, from something to do with genes or upbringing or both.

Maybe the universe is not deterministic. Maybe, as the physicist Max Born once said, ‘Chance is a more fundamental concept than causality’ when it comes to human affairs in general, and crime in particular. Maybe, just by chance, the light from a passing coach-and-four happened to glance off the blade of the axe while the criminal was standing in the pawnbroker’s doorway, and accidentally gave him the idea. Maybe that’s what happened.

Well, maybe. But to invoke chance in human affairs hardly brings us closer to resurrecting free will. You cannot possibly be asked to accept either praise or blame for some chance event in your life, some passing coach-and-four, some event that just happened to happen. We seem to be stuck again.

None of this will prevent the law from punishing a criminal for acting illegally, and perhaps that’s only right. None of it will prevent us, either, from feeling proud of the better or more decent things we accomplish in life. If that is an illusion, it’s no bad illusion to have.

Thank you for reading this newsletter. I hope you find this topic as interesting as I do. If you would like to keep receiving this kind of material in your inbox, every week, for free, please remember - subscribe, share, like, restack!

Raskolnikov and Laplace images provided courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided so that you can read more about anything you found particularly interesting.

[i] CF Strawson, Galen: Your Move – The maze of free will, The Stone Reader – Modern philosophy in 133 arguments, ed. Peter Catapano & Simon Critchley, Liveright Publishing Corp, New York, 2016, pp145-9

[ii] Fried, I; Mukamel R & Kreiman, G: Internally generated preactivation of single neurons in human medial frontal cortex predicts volition, Neuron, February, 2011, 69(3) pp548-62

[iii] Buccella, A & Dominik, T: Free will is only an illusion if you are, too Scientific American, Jan 16 2023

[iv] Baumeister RE, Crescioni AW & Alquist JL: Free will as advanced action control for human social life & culture, Neuroethics, 4(1), pp1-11

[v] Knobe, J: Experiments in philosophy, The Stone Reader, op cit, pp141-4

Great stuff. Though entirely beside the point of the discussion I was intrigued by the 256 neurons idea in part because this signals RAM and early computing, 256 being the highest number held in one byte, or 100000000 in binary. Had to google Dr Fried (who almost certainly prefers to use the German version of his name and not pronounce it as if it were English) if only to see whether he did his work in the early years of microcomputers. At a guess he could easily monitor 256 neurons but 257 would have required twice the capacity. That is neither here nor there. More to the point, the legal argument for accountability even if free will can be shown to not exist at all could lie in the concept of regulating societal behaviour through mutual faith in a rules based system. Getting rid of the associated connotations in, say, compensation is hence attempted by using the concept 'culpa' over 'guilt'. Semantically it makes no difference at all but the drift is that those causing harm or loss can be liable for damages despite the harm being unintended. Free will or not, harm may happen as a consequence of actions where you should have known better and the societal fix is to make you liable for damages. If free will is not assumed should we then consider the results of our actions to be accidents, in which case we are not responsible for the direct or indirect consequences. Perhaps the fallacy is the absolutist binary view of freedom of choice or free will if you like. Imagine a course of action determined 80% by free will but 20% by circumstances entirely outside our control, perhaps the reflected glint in the axe in the example. Can such an example be used to demonstrate the absence or presence of a free will? If constrained by 20% is the will free or not?

Excellent and stimulating article! There are so many positions on determinism and free will, but I do like the link to Russian literature and the device of putting the reader in the role of offender.

Talk yourself out of a job if you’re not careful 😉.