CRIME’S HIERARCHY OF NEEDS

Murder; The Black Dahlia; serial killing; Maslow’s hierarchy of needs; self-actualisation; terrorism

By the middle of the last century, a new trend was emerging in the developed world, invisible at first as a black snake sliding off tyres. First came Leopold and Loeb. They senselessly battered to death a child named Bobby Franks. I say ‘senseless’ because that was the very point. The pampered, wealthy students had decided to demonstrate their effortless superiority to the old moral rules that bind lesser mortals like you and me. They imagined that the best way to do that was through an act of gratuitous violence and evil. You or I might ask, why not an act of gratuitous decency and kindness? Such a question would only reveal how hopelessly benighted and very very ordinary we are.

Proving just how fabulously superhuman he was, Leopold managed to drop his glasses at the site of the murder. He’d forgotten they were in his pocket. Detectives found them with Bobby Franks’ body. (The glasses were pretty ordinary, actually, and Leopold only wore them for a few weeks to try to cure headaches. The only really distinctive thing about them was a hinge which was sold through only one outlet in Chicago. That made it easy enough to track down their owner.)[i]

In 1952, a man named Herbert Mills took a woman on a date and strangled her to death. His motive was as non-existent as his conscience. He didn’t have a reason to do it: he just did it. In 1959, Penny Bjorklund shot a man for no other reason than that she wondered whether she’d be able to control her emotions afterwards. In 1966, Robert Smith killed seven people in an Arizona beauty parlour. “I wanted to get known,” he said, “to get myself a name”.[ii] That’s a very revealing statement. It speaks to the psychological state of these criminals.

All five – Leopold, Loeb, Mills, Bjorklund, and Smith - were momentarily flung into a spotlight that they desperately hungered for, but which revealed nothing but their lack of suitability for it. Too lazy or talentless to deserve the attention, they’d taken the worst shortcut imaginable.[1]

And then there were the serial killers. The Green River Killer telephoned a homicide detective’s wife to taunt her about her husband’s incompetence.[iii] All he wanted was to make himself feel clever. Charles Manson’s infamous, murderous “Family” liked to watch television news together, eager to hear everything the reporters had to say about them. The Zodiac Killer used to send elaborate ciphers to the police, giving them clues that no one could solve. He was flaunting what he considered to be his own intelligence. Wichita’s serial killer, Dennis Rader, did something similar. One policeman was asked to summarise the notes Rader wrote to the force. He said, “Here I am. Pay attention”.[iv] It was exactly that kind of idiot gloating that led to Rader’s capture.

When John Frazier murdered an entire family, he left the police an actual letter.[v] Here he was. Pay attention. Ted Bundy, interviewed in prison, was offended to discover that journalists wanted to discuss his crimes. He’d expected them to be interested in him, Ted Bundy, superstar. Who wouldn’t be interested? Here he was...

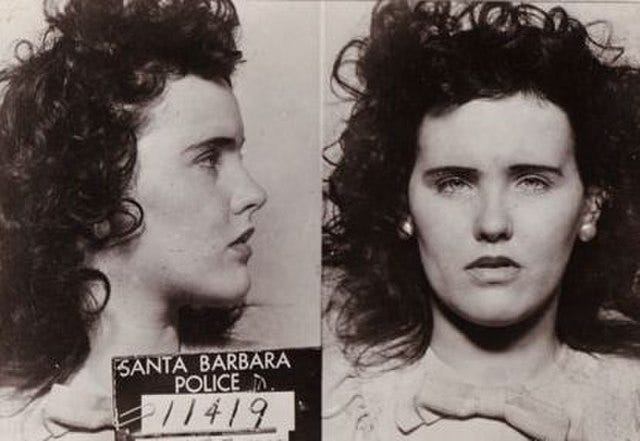

Los Angeles, 1947: The murder of a bit-part actress named Elizabeth “Betty” Short. This poor woman had wanted to become famous, too. She achieved her goal: although ‘notorious’ might be a better word. Short was to become the subject of countless articles, books, websites, even a novel by James Ellroy, filmed by Brian DePalma. Both novel and film were called The Black Dahlia, the name by which Betty was known. In death, she was the Sharon Tate or Nicole Brown of her day. Nothing sells more newspapers than a sexy woman horrifically murdered.[vi] And this was truly horrific. Someone had cut Betty in two at the waist and drained her blood. Although the number of suspects climbed into the thirties,[vii] no one knew who did it or why. There were as many theories as there were imitators.

Yes, imitators. You may wonder how anyone could imitate something so repellent. The answer lies in the psychological concept of ‘ego satisfaction’. It means exactly what it sounds like. The killer was the master. Betty (pretty, talented, alive) was his slave. He got to make the decisions. Here he was...

One year earlier, a British conman named Neville Heath had been arrested for two sadistic sex murders. A rather ordinary fellow, Heath liked to pass himself off as glamorous “Lord Dudley”, or “Capt. Selway, MC”. He’d once been court-martialled for wearing inappropriate military decorations.[viii]

In France, Marcel Petiot offered to help sixty-three refugees escape the Nazis. He gassed them to death and burned the bodies. He was insecure and it made him feel powerful.[ix]

All these people, so violently and pathetically desperate for the same consolations. Just what exactly was going on?

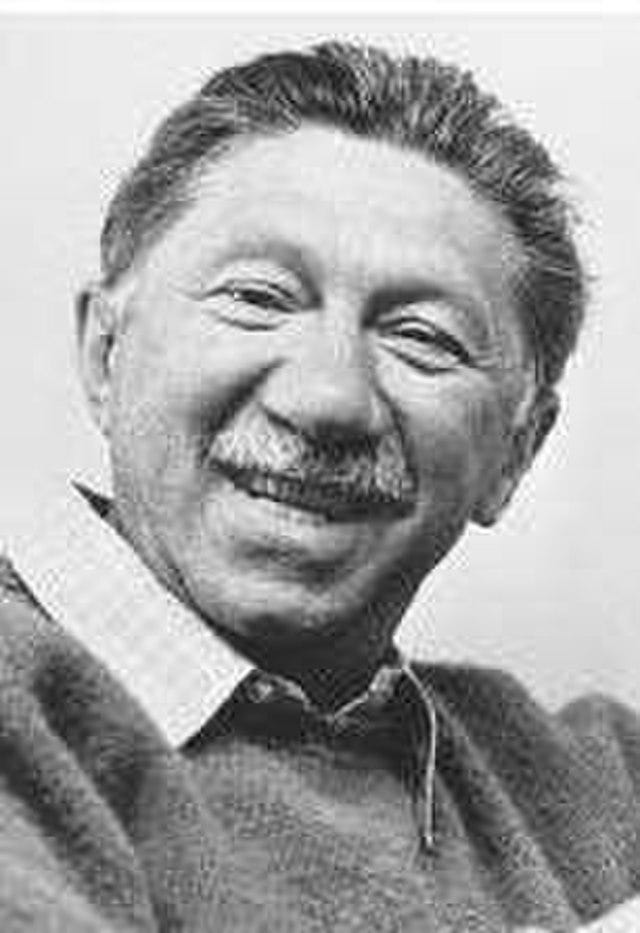

Psychology offers us at least one possible explanation. In 1943, the humanistic psychologist, Abraham Maslow, developed his famous Hierarchy of Needs. It was a model of human motivation. It became so famous that, like just a few other terms from Psychology (anal retentive; Freudian slip; group think) it has entered the everyday vocabulary of most English speakers. It has been just as influential in Management as Economics as Psychology.

Like other models in Psychology (Freud’s model of the human mind, in which you and I struggle constantly, tormented by the opposing demands of our good, rational, socialised self and those of the biological, selfish id, comes to mind) Maslow’s hierarchy of needs doesn’t have too much empirical, scientific support: but, like them, it doesn’t seem to need it. After all, it’s a terrific descriptive account. It gives us a metaphor to use – one that seems to tell us something about what it means to be a human being. That’s why it has had such staying power.

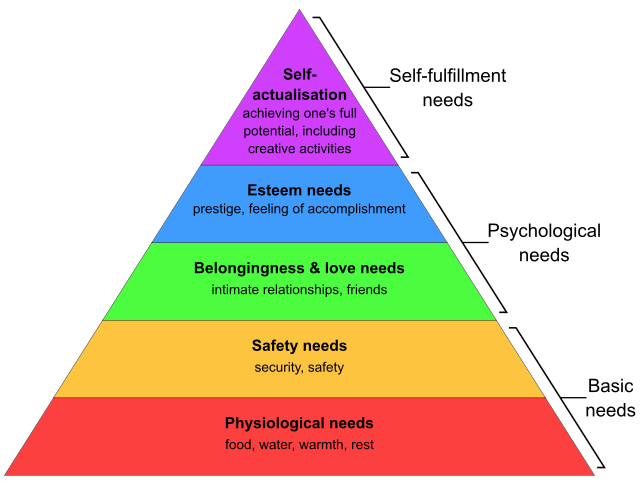

It has five levels. Each one emerges when those below are satisfied. At the bottom come physiological needs: food, water, air. A beggar thinks he’d be happy if only he had a hot meal every day. But then he starts to want more: a roof over his head, a key for the door. These are security needs. Satisfy them and he starts to need love, belonging, sex. Next come esteem needs: status, recognition, and freedom. The final stage is one that few ever reach. It is self-actualisation, the need to fulfil one’s potential. Here is a picture:

Maslow’s levels correspond to different periods in criminal history. Before the nineteenth century, crime most often reflected survival needs. The notorious criminals, Burke and Hare, for instance, killed people and sold their corpses to needy medical professionals for cash. No one enquired too closely where the endless stream of bodies came from. The so-called ‘resurrection men’ needed money for food as badly as the medics needed cadavers for dissection.

The Industrial Revolution made domestic murder notorious. People killed in order to safeguard their own security. The nineteenth-century murderers, Kate Webster and William Palmer, are excellent examples.

Kate Webster actually lived inside her victim’s home. A petty criminal by trade or habit, she had already served four terms for robbery when her final mistress, Julia Thomas, threatened to fire her. Her response was homicidal: “in the height of my anger and rage I threw her from the top of the stairs to the ground floor”.[x] She cut up the body with a razor, meat saw, and carving knife, and then boiled the bits in a copper kettle. In Twickenham, someone found a foot. In Barnes, someone else opened a hatbox and found a torso inside. Impersonating her victim, Kate pawned her possessions. Not one for waste, she also sold the body-fat for dripping.[xi] No surprise that her likeness, too, soon appeared in the Chamber of Horrors. Julia Thomas’s skull eventually appeared in Sir David Attenborough’s back garden.[xii]

William Palmer was a surgeon – a proper, paid-up member of the middle classes. Respectable, or so you’d imagine. You might imagine him hobnobbing with, say, Sherlock Holmes’s companion, Dr Watson. How to explain the fact that he seemed to have poisoned no fewer than fourteen people to death? People remarked on how ordinary he looked. If Palmer could be a criminal, it seemed, anyone could be.

Coming into the twentieth century, decades of prosperity meant that crime began to reflect self-esteem needs.[xiii]

The very pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy is only sparsely populated. One such lonely figure may be Philippe Petit. In the 1970s, the high-wire artist crossed, successively, between the towers of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris and the pylons of Sydney Harbour Bridge. He used not a single piece of safety equipment. Illegal it may have been, but it would take a special sort of killjoy to disapprove. Next, Petit conceived “the artistic crime of the century”.[xiv] Smiling and laughing, he waltzed between the roofs of New York’s Twin Towers, thrilling onlookers.

Another example is George King-Thompson. He was imprisoned in October, 2018, after free-climbing London’s Shard. “I feel most alive when I’m doing these things,” he told one reporter. “If you can control the fight-or-flight mechanism, you have your own little superpower”.[xv]

Here is Maslow himself on the self-actualising person: “no worry, no anxiety, no apprehension, no foreboding”[xvi]. That sounds like someone with a superpower, doesn’t it? You can’t get much more self-actualised than that.

I mentioned that the pinnacle was only sparsely populated. Only about 2% of human beings achieve self actualisation. Eleanor Roosevelt and Albert Einstein were examples. Maslow himself, writing in 1970, could think of only eighteen in total. Maslow died of a heart attack in the same year, and one has to wonder whether the two things were related.

Back to self-esteem needs. Luka Magnotta may have been driven by similar needs to Manson, the Zodiac Killer, Heath, and the like. The delusional killer and pet-torturer posted videos of his crimes on the internet. He was apparently trying to become as famous as he thought he deserved to be. The murder he committed was an attempt to re-create a scene from the film, Basic Instinct. How vain was Magnotta? He was captured while admiring his own mugshot in an internet café. His crimes feature in the Netflix documentary, Don’t F**k With Cats. Twice during the course of the documentary, we are told that the former model doesn’t “look like a killer”. No, he doesn’t. He looks like a desperately-needy, self-obsessed narcissist.

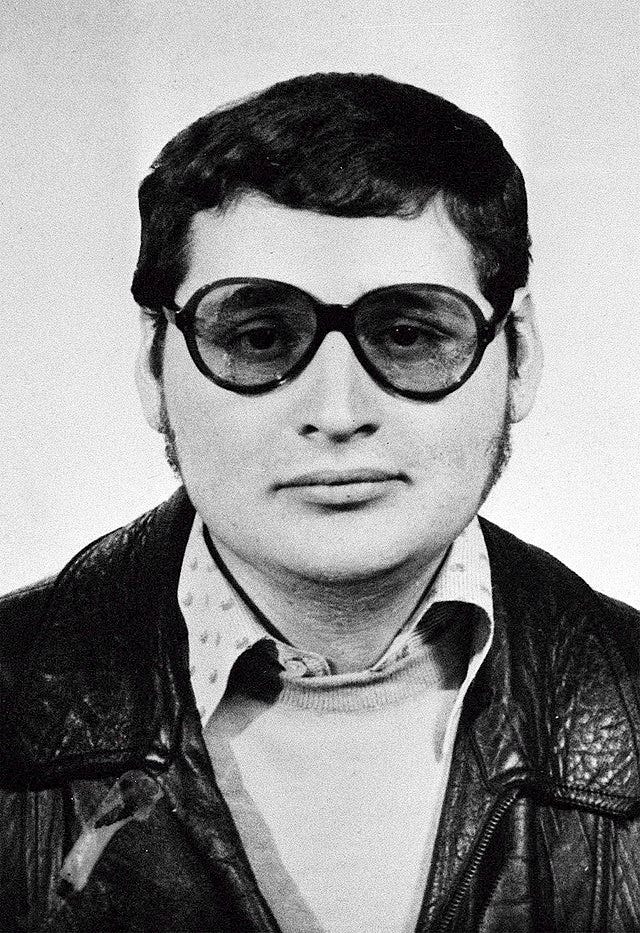

Consider today’s terrorists. Their crimes are surely “mixed up with the dubious attractions of celebrity, self-realization and the desire of its practitioners to appear on screen, even if wearing a mask”. The glamour-boy terrorist is “exercising his one and only talent”.[xvii] As talents go, it’s a sorry one. There is nothing unique about the ability to make a hell of other people’s lives. Anyone can do it. Take the woeful example of Ilich Ramirez Sanchez, pretending to believe in a version of Marxism that did nothing but give him an excuse to strut about for the cameras as the costumed supervillain called Carlos the Jackal.

It takes someone special to be not only talentless but also over-rated. Carlos the Jackal was certainly special, but not in the way he liked to think. Although he was portrayed as a highly-trained, ruthlessly-efficient agent of the KGB, possessing a megalomaniac plan to destabilise the West with a daring series of assassinations and hijacks, it turns out that he was nothing of the kind. According to a Guardian article, he was not ‘a master terrorist working hand in glove with ruthlessly efficient regimes to launch attacks in the west, but of an arrogant, demanding, and unreliable terrorist entrepreneur who manipulated the anxieties of insecure decision-makers and the ignorance of security officials from the Baltic to the Black Sea until they finally ran out of patience’[xviii]. Patience was only too easy to lose when it came to a grandstanding psychotic with a weakness for blowing people up.

What can we say about such a creature?:

“Society has refused to recognize his uniqueness; it has insisted on treating him as if he were just like everybody else. By committing a crime that makes headlines, he is administering a sharp rebuke. He is making society aware that, somewhere among its anonymous masses, there is someone who deserves fear and respect...”[xix]

It’s clear why so many “master criminals” seem pleased to be caught. Otherwise, who’s going to know they are master criminals? They need the attention. Here they are…

If you like what I am doing on this Substack, please consider Liking, restacking, subscribing, or even making a Pledge. It all helps, it really does!

References supplies partly out of academic habit; partly so that you can chase up anything you find particularly interesting.

All pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons

[1] Author John Toland reports, in a Kansas cellhouse, a sign saying Crime Doesn’t Pay But The Hours Are Sure Good.

[ii] Wilson, Colin, A Criminal History of Mankind, Granada, London, 1984, pp215-6pp11-12

[iii] Norris, Joel, Serial Killers – The growing menace, Arrow Books, London, 1997, p37

[iv] Gibson, Dirk C, Serial Killers Around the World: The Global Dimensions of Serial Murder, Bentham Science Publishers, London, p129

[v] Wilson, Colin, op cit, pp12-14

[vi] Swezey, Stuart: “Introduction to the second edition” in Gilmore, John(2): Severed – The true story of the Black Dahlia, Amok Books, Los Angeles, 2006, Kindle edition, Loc81-83

[vii] blackdahlia.web.unc.edu/suspects

[viii] Neustatter, W Lindesay: The Mind of the Murderer, Christopher Johnson, London, 1958, pp107-110

[ix] Wilson, Colin, op cit, p616-7

[x] Kate Webster, quoted in Rudd, Matt: “Scandal! Horror! Homicide! – Murders by gaslight”, Sunday Times Magazine, October 5, 2014, pp26-31

[xi] Thomas, Donald: The Victorian Underworld, John Murray, London, 1998, p66

[xii] Carver, Stephen: The 19th Century Underworld – Crime, controversy & corruption, Pen & Sword, Yorkshire,2018, p147

[xiii] Wilson, Colin, op cit, pp15

[xiv] Krznaric, Roman: The Wonderbox – Curious histories of how to live, Profile Books, London, 2011, p285

[xv] Evans, Hannah: “Prison isn’t much of a stretch once you’ve knocked off the Shard”, Sunday Times, January 19, 2020, p33

[xvi] Maslow, Abraham: Toward a Psychology of Being, Van Nostrand, 1962, p 67

[xvii] James, Clive: The Meaning of Recognition - New essays 2001-2005, Picador, London, 2007,p347

[xviii] Link to Guardian article here

[xix] Wilson, Colin, op cit, p42

And that *you* for your comment, Jeffrey! The Hierarchy of Needs is a brilliant descriptive tool, I agree. It sometimes gives me a means of telling people why, after an hour in a museum, I just can't take in any more culture. My feet hurt! Perhaps, as some psychologists have said, it functions better as a description than a prediction, but there's room for that in science, after all.

"His motive was as non-existent as his conscience. He didn’t have a reason to do it: he just did it."

I do wonder if there really is such a thing as a human action without a motive. Of course, sometimes people cannot explain, understand, or properly express their morives, or they don't want to. But strangling somebody to death is a decision, and it means some effort and risk of punishment. I am looking forward to hear your opinion.