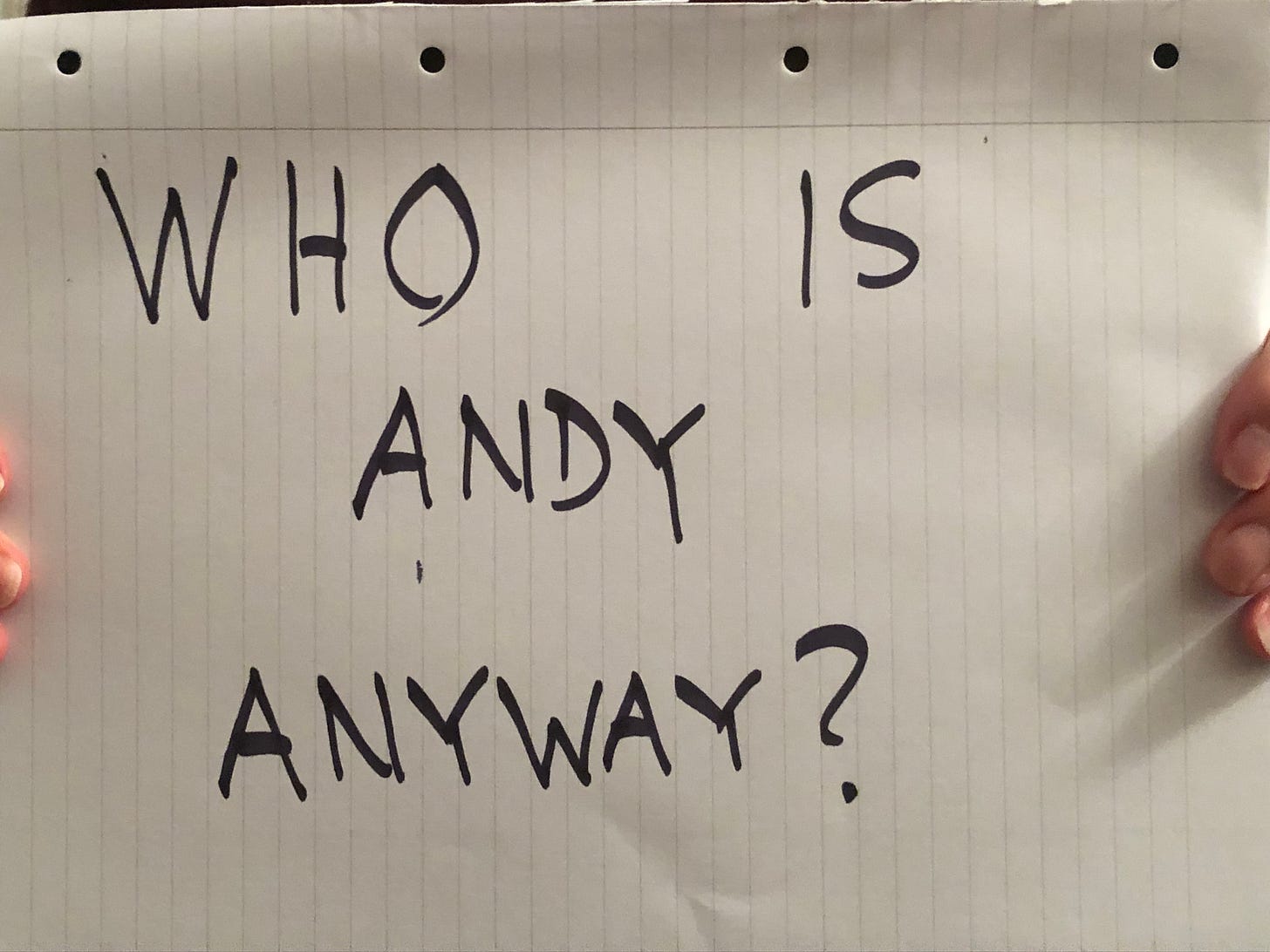

CONSPIRACY THEORISTS: WHO ARE THEY ANYWAY? Part 2

What exactly makes for a conspiracy theorist?

In last week’s exciting episode, we took a long hard look at your cousin, Andy. You know, the conspiracy theorist. We asked whether it might be possible to make a profile of Andy, something along the lines of what FBI offender profilers do for serial criminals. Does Andy fit the profile?

If you missed last week’s episode, you’ll be pleased to know you can catch up just by clicking here.

What is he like? Turns out, Andy, like most conspiracy theorists, is male (he isn’t called Andie), may belong to a minority ethnic group, is generally a suspicious sort, and probably believes not just one conspiracy theory but a whole spaghetti-junction full. Conspiracy theories, after all, are a garden of forking paths.

A recent (ish - 2022) paper in the Journal of Research in Personality[i] reported on no fewer than twelve ’correlates’ of conspiracy theory belief (CTB). In lay terms, that just means ‘characteristics Andy may – or may not – have’. They were:

cognitive ability

narcissism

paranoid ideation

pseudoscientific beliefs

religiosity/spirituality

schizotypy

low self-esteem

plus five personality variables: neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, conscientiousness, and agreeableness. These variables (psychologists usually call them ‘factors’) are often taken to represent the fundamentals of human personality. They are the basis of two of the best-known models of personality, known as Big Five and OCEAN respectively.

Many of the ‘correlates’ are more or less self-explanatory, but let’s enlarge on what some of the more obscure ones mean.

Narcissism – no surprise - involves ‘elevated levels of self-importance and entitlement’. Narcissists don’t like to be thought wrong. Hence they may be wary about challenging whatever conspiracy theories they happen to hear. They worry about being mistaken and ending up in the foolish corner. Bear in mind that espousing conspiracy theories is also a way of getting attention, which narcissists, of course, tend to crave. Finally, they like to feel uniquely well-informed; armed with secrets that others do not suspect.[ii]

Although the phrase ‘paranoid ideation’ has a pretty serious ring to it, it doesn’t necessarily imply full-blown paranoid schizophrenia. Many of us have a ‘tendency to be suspicious and to ascribe bad intentions to other people’ without necessarily requiring clinical help (maybe we just read the political news). It’s simply a personality trait that, like others, may happen to be pronounced in certain people. Andy, perhaps.

Odd though it may seem, ‘religiosity’ does share a few features with CTB. Both ‘can result from sense-making when facing challenging events’; both ascribe ‘agency and intentionality to powerful entities’; and both represent ‘meaningful but unfalsifiable world views’. Don’t interpret this to imply that psychologists think either religion or conspiracy theories are wrong. It doesn’t necessarily mean that. As I mentioned last week, conspiracies do sometimes happen.

‘Schizotypy’ refers to a personality features like coldness and lack of comfort in close relationships. Schizotypal people sometimes have difficulty understanding social cues such as yawning and the words ‘Well, I must be going’. They may have unusual or even magical beliefs. We can measure it using scales that cover such proclivities as magical thinking and belief in telepathy, astrology, and alien visitation.

So much for definitions. You’ll be hungering to know which variables correlate with CTB. Let’s put the strongest correlates here, in order from top to bottom:

pseudoscientific beliefs

paranoid ideation

schizotypy

narcissism

(Fellow stats-heads will want to know that the r values were, respectively, 0.46; 0.34; 0.30; 0.28. If you’re not a stats-head, feel free to ignore this bit.)

Weaker correlates were these:

religiosity

cognitive ability

self-esteem

agreeableness

neuroticism

(r values: 0.14; -0.13; -0.06; -0.07; 0.04.)

Three of these five factors were negatively correlated, which means that as they went up, CTB, unexpectedly, went down. They were cognitive ability, self-esteem, and agreeableness.

As for the three remaining personality factors, well, there was ‘considerable uncertainty’. Indeed, as the authors of the study say, ‘There is no strong evidence that Big Five personality traits are relevant in the context of conspiracy theories’. We can’t say much, then, about conscientiousness, introversion, or openness, except that they don’t tell us much. In the case of introversion, that might be a surprise. After all, we tend to think of conspiracy theorists as friendless loners who spend most of their days hanging out in the cellar, untouched and dusty as old wine. That doesn’t seem to be the case.

I don’t know about you, but I can’t help feeling slightly disappointed. Conspiracy theorists are not quite what I imagined. Perhaps we should be cheered by the thought that these rugged non-conformists refuse to fit the stereotype. Good for them, I guess. Maybe we can’t pick Andy out of a crowd so easily. Maybe he blends in. No great surprise, perhaps, when we remember just how many Andys there are. When just about everyone is an Andy, just about no one is an Andy.

Introversion, as I say, might have been a surprise. So was one other factor on the list: cognitive ability (which is to say, in that mealy-mouthed academic manner, intelligence).

Intelligence, of course, is not the same thing as education. If you’ve ever encountered a real-life example of the stereotypical ‘absent-minded professor’, (or one of those many individuals who possess a bunting of advanced degrees but nevertheless can’t park a car,) you’ll know what I mean. Even so, the two do tend to go together. More intelligent people tend to have more years in education, and we’d hope that education would increase a person’s cognitive ability, so that correlation sort of makes sense.

One paper indicates that highly-educated people are least likely to be conspiracy theorists.[iii] The author made some interesting points that I’d like to share with you.

For one, there are plenty of reasons to suspect a relationship between education level and CTB: at least four. Here they are:

cognitive level of complexity,

ability to control

social status and

self-esteem

People with high levels of education are familiar with explanations in terms that scientists refer to as ‘multivariate’. Conspiracy theories, by their very nature, minimise complexity. They explain events in straightforward cause-and-effect terms. Why did 9/11 happen? Because the American military wanted a war. Why did Princess Diana die? She annoyed the Royal Family. Doesn’t get much simpler than that. No wonder the ability to deal with multi-causal, complex ideas indicates resistance to CTB.

Last week, I mentioned conspiracy theorists’ ‘perennial sense of powerlessness’. People with high education also (usually) have privileges, jobs, incomes. They feel as if they’re doing well. They may very well not require conspiracy theories to explain adverse events, for the simple reason that they have relatively few adverse events to explain.

Educated people have the ability to control their environment. They can solve complex problems and acquire all sorts of useful social skills. Both factors decrease their sense of powerlessness. Hence they may have little need to turn to CTB.

I don’t know about you, but I find these arguments pretty convincing. Again, though, Andy managed to surprise me. Some of these mechanisms seemed to work; others did not.

We already dealt with self-esteem, above. There’s no link. As I’ve mentioned in PREVIOUS SUBSTACK ARTICLES, self-esteem is a complicated topic, much more so than we often suppose. It is not always the good thing we tend to think, and often a very bad one. There’s no link with social status either, as far as we can tell.

That leaves with just two really robust predictors of CTB. They are cognitive complexity and feelings of power over one’s environment.

Now you know what Andy’s like.

There’s much more to be said on the topic of conspiracy theory and a heap more research to share with you. You’ve probably gathered that I love this topic. If you do too, let me know. I’ll write another newsletter or two. Meanwhile, Crime & Psychology fan, do me a solid and smack that blue button like you’re its mama. Your animosity towards the blue button really does help to keep the newsletter going.

[i] Stasielowicz, Lukasz: ‘Who believes in conspiracy theories? A meta-analysis on personality correlates’, Journal of Research in Personality, Volume 98, June 2022, 104229

[ii] Heins, V: ‘Critical theory & the traps of conspiracy thinking’, Philosophy & Social Criticism, 33(7), 2007, pp787-801

[iii] van Prooijen, J. -W, op cit.

Simple intellect and a feeling of powerlessness. The flip side of cognitive complexity and feelings of power over one's environment. Yes, that explains a lot about the malaise that plain folks feel today. How do you avoid the malaise? Education (if your brain can utilize it) and independence from the power plays of the polite world, i.e. what Hobbes called Leviathan. And in a world where education, health care and the basic needs of life (shelter, food and, maybe, love) are being priced out of the reach of lots of folks, independence is harder and harder to maintain. Last year, young people were being coached to study STEM to gain control of their lives; this year we are beginning to hear that in the face of change, young people should adjust their sights and become welders or well-paid influencers in order to sustain a sense of control over their environments.

That kind of inchoate rambling thought comes out of Jason's deep dive into conspiracy theories and the people who utilize them to explain the world to themselves and then to others. I want more education on the subject.