WHAT WE THINK ABOUT WHEN WE THINK ABOUT CRIME 2

Memory; mugging; police interviews; ‘truth serum’; false memories; Rorschach ink-blot test; conspiracy theories

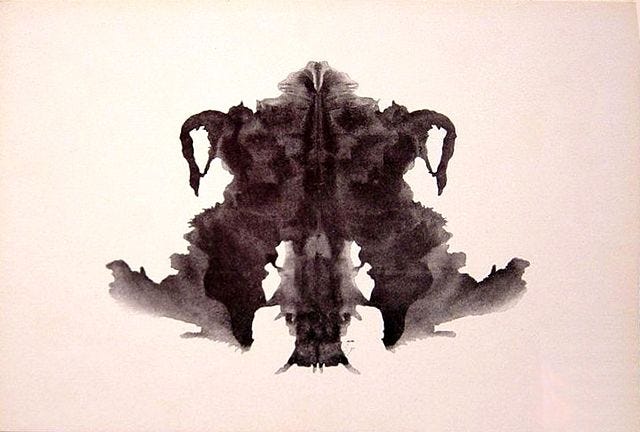

What does this picture tell us about Crime & Psychology? Even better, what does it tell us about Batman? Read on, Crime & Psychology fan: all will be revealed soon!

In last week’s pulse-pounding episode, I introduced you to the so-called information-processing model of human thinking. Cognitive psychologists like to conceive of our minds by analogy with computers, and their own science by analogy with Computer Science. These analogies open up whole new, fascinating, ways of modelling the phenomena that are going on inside our minds. Two important ideas I mentioned were, first, limited-capacity processing (which implies that we have fewer resources at our disposal than we tend to think, and have to use them very parsimoniously) and, second, schemata p- those ‘packets of knowledge’ we store inside our minds, and which help us to make sense of whatever we happen to be attending to at the moment.

Cognitive psychologists often use flow-diagrams to illustrate thinking processes. One example was the Modal Memory Model. I reproduce it again here, because we are about to go back to it:

Take another look at that Modal Memory Model (this will be the last time, I promise). Implicit in it are the three basic memory processes. Psychologists call them encoding, storage, and retrieval. Think of them like copying files to a flash drive, keeping them there, and opening them again later, at the appropriate time.

Schemata, to state the obvious, are stored inside the mind. That means they pre-exist any information you may be busy encoding. The information is new, but the schemata are old. This simple fact is liable to have a big effect on eyewitnesses.

Let’s say you happen to witness a mugging. You will already have a schema for ‘muggers’ stored in your mind (it may not be a terribly detailed one, if you are lucky enough not to have witnessed, or suffered, any muggings yourself). The schema activates as soon as the mugging takes place. It guides the way you process the details. In this sense, encoding is the vital stage: the material you encode and the material you end up retrieving later, during the police interview, will both depend, in part, on the contents of the schema.

The implication is this: not much that happens later can substantially affect the way your mind represents the mugging you witnessed. It was already encoded a certain way: what could possibly change that? There is probably little anyone can do at the retrieval stage to improve the quality of the material you produce. That is why, when psychologists do come up with techniques for ‘improving eyewitness memory’, other psychologists get very excited indeed and dash off to their laboratories to test them. Examples of such techniques have included hypnosis, a phenomenon known as ‘contextual reinstatement’, and the Cognitive Interview, which was devised by a group of psychologists as long ago as 1984 but is still going strong. Do they all work? Well, that is the question.

Incidentally, one other technique you may have heard about is an injection of sodium pentothal, known as truth serum. A terrible name, that, even if it is catchy. A person can lie under the influence of sodium pentothal just as they can lie under the influence of alcohol or hypnosis. It’s just that much more difficult. In the US, the parsimonious criminal-justice system has a second use for sodium pentothal. It is used as part of the execution process when a convict opts for lethal injection.

A psychologist named Elizabeth Loftus built a long and prestigious career out of discovering factors that might influence people’s memories even after the event in question has passed. She concentrated initially on eyewitnesses to crimes, but expanded her remit and became an expert in ‘false memories’.

False memory is a phenomenon you may very well have heard of. It has received a great deal of media attention in recent decades, owing to its importance in criminal trials. One particularly startling example is supposed ‘Satanic ritual abuse’. Rumours about it seemed to sweep the world in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Untold numbers of families were broken up on the basis of false memories which seem often to have been implanted by the researchers themselves. As you can see, it is really vital for psychologists to get to grips with false memory. We’ll look at Elizabeth Loftus and her work on misinformation in a later newsletter.

Limited-capacity processing has one more implication we ought to consider. It’s to do with survival.

Most of the history of human evolution was spent in a hostile environment. There was limited food, limited shelter, no medicine, and, worst of all, an abundance of predators who wanted to eat us. Although you and I may live in relatively safe and well-protected twenty-first century homes, our cognitive systems were built in precisely such an unfriendly place. They are positively antediluvian. They were built to keep us going, keep us safe, keep us alive. They are very good at alerting us to food sources, potential mates, and, especially, threats. In a sense, they are actually too good.

We tend to think that we see (and hear, and smell) the world ‘as it really is’ (whatever that means). It’s not true. With only limited processing resources at our disposal, after all, it makes evolutionary sense for us to over-respond to certain aspects of the environment, and under-respond to others. For that reason, our senses lie to us all the time. After all, they have to keep us fed, healthy, and physically intact. When it comes to interpreting the world, therefore, we make more-or-less systematic, predictable errors. The study of these errors is one of the most exciting areas in modern Psychology.

Have you ever woken up in the middle of the night, tense and full of adrenaline, ready for fight-or-flight, because you heard a strange noise in the house? (If you have, it’s not an experience you’re likely to forget in a hurry.)

Of course, it’s pretty likely that it’s just your cat jumping around and maybe swiping ornaments off the mantlepiece, but chances are that you over-react anyway. Perhaps your first thought might be ‘burglar’ if not ‘axe murderer’ or even ‘monster’. Of course, there aren’t any monsters. We don’t believe in monsters, you and I - do we? - because we are rational, postmodern people. On the other hand…it is 4am. Maybe rationality is no help to us at 4am.

Over-reacting in such a situation makes good evolutionary sense. If you think there is an axe murderer in your house, and it turns out just to be the cat, it doesn’t really matter: you’ve lost nothing but a few moments of sleep. If, however, you assume it’s just the cat, but it turns out to be an axe murderer…that’s an error you will not live to regret. One information-processing strategy is fine: the other is not. Prehistoric people who made one too many errors never managed to pass on their genes. Evolutionary history, therefore, simply weeded out one kind of error in favour of another.

Say a family-member – someone you care about, and who shares genetic material with you – goes into an area of the city you know to be dangerous, and fails to call you even though they said they would…well, how do you react? Probably, you start to worry about their safety. You may think about trying to rescue them. If you think they are in trouble, and they turn out to be safe, again it doesn’t really matter: you’ve just had a few moments of anxiety. If, however, you assume they’re fine, but they turn out to be in trouble, it’s a wholly different story. You’ve lost part of your vital support network. Again, one error is fine: the other is not. Evolutionary history has weeded out one in favour of the other.

If you process information as dangerous or threatening, even when it isn’t, you have taken a big step towards survival. Your - and my – cognitive system is constantly making errors, but, on the whole, they are good, cheap, life-preserving errors. The important point is that small errors don’t matter. Big ones do.

You may have noticed that I used the word ‘error’ repeatedly in the last few paragraphs. That was a nod to the phrase ‘Error Management Theory’, which is what we are dealing with here.

We are constantly having perceptions (seeing things or hearing them) based on incomplete information: a cloud that looks a bit like an angel; the Virgin Mary in a grilled-cheese sandwich; a part of a melody that sounds like a favourite song.

This is where many conspiracy theories come from, too. We perceive patterns that are not really there, in data that may not have existed in the first place. Have you seen The Child’s Guide to Conspiracy Theory?: ‘Join the two invisible dots’.

One day, when I was hanging up laundry, Batman’s face appeared in my trousers. I took a picture, because I thought you’d like to see it:

Our cognitive system, so to speak, fills in the gaps. It does so in the interest of saving effort and conserving those precious resources. And the errors we make tell us a great deal about how the system really works.

Interestingly, this is the basis of the famous Rorschach ink-blot test, which you may have heard of. The idea is to expose a patient to an image that is known to have no actual content. Anything they ‘see’ in it, therefore, can only be a product of their own mind. If they see kittens, lovely. If they see a bear on a motorcycle, well, weird, but fine. If they see a monster dripping slime…maybe not so good. Actually, don’t fear if that’s what you see. The ink-blot test isn’t a very good diagnostic instrument:

Bear in mind that human beings are physically weak, social creatures who rely on each other for survival. No surprise, then, that one phenomenon that’s really useful to us is the perception of human faces. They carry a great deal of important information about another person’s suitability as a friend or ally; their age; their state of health and current mood; and so on. Just remember how many times, as a child, you saw faces in the clouds or the moon, in just the same way that some thought they saw faces in the smoke issuing from the Twin Towers. Better to see a face that isn’t there, than fail to see one that is.

The half-glimpsed face of a criminal, partially disguised and poorly-lit…your cognitive system is likely just to fill it in. It may not know what this particular criminal looks like, but it is likely to have a schema for what criminals in general ought to look like.

What criminals ought to look like… There’s a big topic for another newsletter. And if you’d like to be sure to receive that newsletter, please be equally sure to support my work. You can do so very easily. Be brave: bip a bright blue button below!

Modal Memory Model and Rorschach ink-blot test pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons.

I’ve read about a bunch of these things elsewhere but I’ve never seen all of it put together in one place and explained so well. The memory flow chart is very interesting; some of that I learned in an education class, and I’ve used it in my music teaching ever since, but this chart and your text fleshed out what I learned in the class.