THE FIVE STRANGEST EVENTS IN CRIMINAL PSYCHOLOGY

Think it's all glamour at the cutting edge of forensics? Read on...

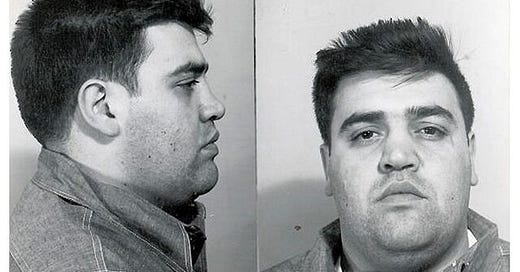

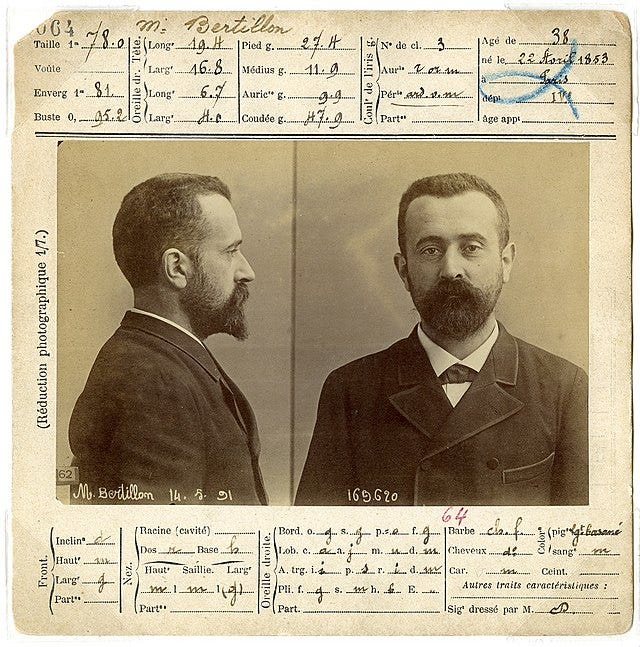

1. Bertillonage was a system developed in the late nineteenth century by the French criminologist, Alphonse Bertillon. The idea was to track recidivists. Bertillonage meant taking numerous physical measurements of criminals, shortly after arrest, to check whether they had ever been arrested before. The probability of two different people sharing the same Bertillon measurements was estimated at 286,435,456 to 1. You can see why police forces around the world adopted the system enthusiastically. But then… In 1903, a fellow named Will West was arrested and transported to Fort Leavenworth. A warder took his Bertillon measurements and checked them against his index cards. He found a second card, under the same name, with the same measurements. The problem was, this second Will West was in a workshop downstairs. The two Will Wests were made to stand side by side. It must have been a disorienting experience for everyone involved, the Will Wests not least of all. ‘This is the end of bertillonage,’[i] said the warder, who took up the new-fangled science of fingerprinting the very next day. To see pictures of the Will Wests, check out this link. The index card below shows Alphonse Bertillon himself.

How strange was that? Please hit a blue button. Thank you!

2. 1975. A psychologist named Donald Thomson appeared on a live television discussion show. He spoke about his area of professional expertise – eyewitness testimony. He returned home after the discussion only to be arrested later that evening. He assumed the police were harassing him - but it was more serious than that. It turned out Thomson was accused of breaking into a woman’s home and raping her. The crime, it transpired, had occurred at the precise time Thomson was on television. The police officers asked whether Thomson had any exculpating witnesses. He was able to tell them that he had an entire TV audience, an official of the Australian Civil Rights Committee, and an Assistant Commissioner of Police. The officer reportedly replied, ‘Yes, and I suppose you’ve got Jesus Christ and the Queen of England, too’. The victim had been attacked while she was watching the show. She correctly identified his face as having been visible at the time, but incorrectly identified it as the attacker’s.

If that story surprised you, please hit a blue button. Thank you!

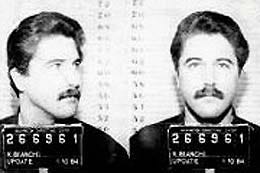

3. Kenneth Bianchi was one of two cousins arrested in the famous Hillside Strangler case, which occurred in Los Angeles in the late 1970s. Ten young women were murdered. Bianchi by all accounts appears to have been an urbane and somewhat charming type. Police officers wondered among themselves whether he could really have had anything to do with the murders. Bianchi had a television in his cell, and appears to have seen the famous mini-series, Sybil, starring Sally Field as a young woman with multiple personalities. Now Bianchi claimed that a second personality, named Steve Walker, had committed the murders. An insanity plea would be a problem for police, since Bianchi was not only a suspect, he was also the most important witness against Angelo Buono, his partner in crime. A number of psychiatrists confirmed that Bianchi did appear to have two distinct personalities, one of them murderous. Martin Orne, a world expert on hypnosis, disagreed. Indeed, Bianchi seemed to be overplaying his hand. For instance, Orne told the hypnotised suspect that his attorney was sitting in a chair nearby[ii]. Bianchi shook the hallucination’s hand: something Orne had never seen a hypnotised subject do. He also told Bianchi he was puzzled that he had just two personalities, since most people with the disorder had at least three. Soon a third personality – a frightened child named Billy – appeared. Orne was convinced that Bianchi was malingering. At length, Bianchi himself admitted the same thing in court[iii]. (You can see some footage here.)

If you like this material, please hit a blue button. Thank you!

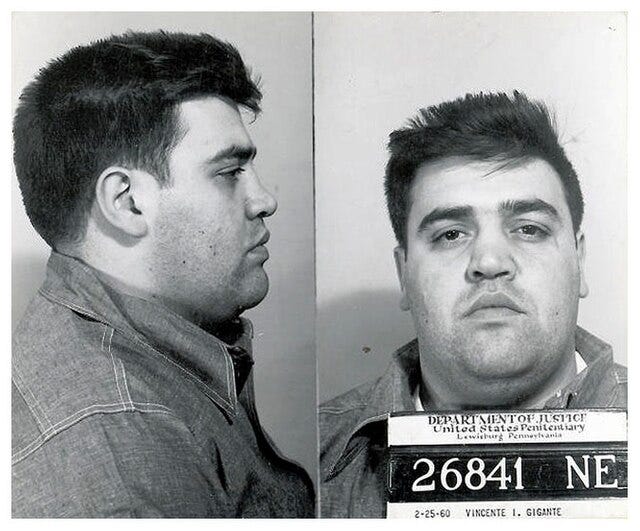

4. Vincent ‘The Chin’ Gigante was the head of New York’s Genovese crime family for a quarter of a century from 1985. Not that the FBI knew that. They believed Fat Tony Salerno was running the family and that Gigante was suffering from a range of psychiatric disorders that rendered him unable to ‘run a candy store, much less a crime family’[iv]. Gigante spent a lot of time wandering the streets of Greenwich Village in pyjamas and slippers. Sometimes he’d mumble to himself. Sometimes he’d expose himself; other times he’d urinate in the street. Once, spotting some local FBI surveillance, he fell to his knees and prayed. The charade began in 1969, shortly after Gigante learnt he was under investigation in a bribery case. Suddenly, psychiatrists were testifying that he was ‘psychotic, mute, schizophrenic’ and ‘a candidate for electroshock treatment’. The Mafia boss was ruled mentally unfit to stand trial. The case was dismissed. By the 1970s, Gigante was having frequent ‘tune-ups’ at psychiatric facilities, usually when the phrase ‘grand jury’ was mentioned in his hearing. He knew the FBI wasn’t about to drag him out of a psychiatric ward and into a courtroom. When Gigante finally did appear in court on a RICO charge in 1990, the press called him ‘The Oddfather’. He was back in court in 1993. This time his psychiatrists said he was suffering from hallucinations and Alzheimer’s disease. A judge decided they were wrong. Imprisoned at last, Gigante continued to act like a psychiatric patient, all the while running his crime family from behind bars. In 2003, he found himself miraculously cured of everything that had been wrong and confessed to conning America’s top psychiatric talent for decades. He admitted to obstructing justice. In return, the prosecution dropped his racketeering charges.

If you are enjoying this newsletter, please hit a blue button. Thank you!

5. Certain patterns of brain activity correlate with psychopathic tendencies in personality. In particular, researchers look at the limbic system and frontal lobes. The former is the part of the brain that becomes active when we experience emotions like shock or anger. The latter seem to be associated with so-called ‘response inhibition’ – that is, the ability that you and I, (and other readers of the Crime & Psychology newsletter,) have to dampen down these feelings and not act upon them. Violent offenders generally, and murderers especially, seem to have a decreased abilities when it comes to ‘response inhibition’. The researcher James Fallon was leafing through a stack of brain scans of serial killers, schizophrenics, depressives, and members of his own family. One of the latter batch was, he noticed, ‘obviously pathological’[v]. He decided he had to break the seal that told him which family member it could be. It turned out to be no less a person than James Fallon. His first thought was the same as yours or mine might be: he figured his research was all wrong. Perhaps these areas of the brain were not associated with criminality after all. Fallon took further tests. The news just got worse. He had, for instance, a variant of the MAO-A gene that is linked with aggressive behaviour. His ancestors included seven (alleged) murderers, including the notorious Lizzie Borden (who, you’ll remember, supposedly ‘took an axe/And gave her mother forty whacks’). Fallon has committed no major crimes. But he admits, ‘I’m kind of an asshole, and I do jerky things that piss people off’. We all know people like that, though, don’t we? To what does Fallon attribute his decent behaviour and successful career? He was brought up in a secure and loving household. Till next time, Crime & Psychology fan – be good to each other and bang a blue button. Thank you!

All images courtesy of WikiMedia Commons.

[i] Thorwald, Jürgen: The Marks of Cain, Thames & Hudson, London, 1965, p134

[ii] Untitled Document (upenn.edu)

[iii] Did Hillside Strangler Kenneth Bianchi Have Multiple Personalities? | Crime News (oxygen.com)

[iv] Barry Slotnick, quoted in Raab, Selwyn: Five Familes – The rise, decline and resurgence of America’s most powerful Mafia empires, Robson Books, London, 2006, p544

[v] James Fallon, quoted in Stromberg, Joseph: ‘The neuroscientist who discovered he was a psychopath’, Smithsonian Magazine, November 22, 2013.

Thanks for sharing really intriguing stories about odd cases in crime. I wonder what ended up happening to Fallon? Did he still argue that perhaps he had s propensity to commit such crimes? Is perhaps his interest in those kinds of activities correlated with engaging in those kinds of activities?

What a super fun read!