THE CONCORD PRISON EXPERIMENT

Psychedelic drugs; hallucinogens; prison; academia; literature; bureaucracy; therapy; recidivism

Here is one of the more outlandish episodes in criminal psychology. It features two academics from Harvard University, several fistfuls of hallucinogenic drugs conjured out of Mexican mushrooms, a utopian vision, thirty-six old lags, a naked Allen Ginsburg, and - just discernible amid the chaos - a proper scientific experiment. It also features a psychologist who was called the ‘most dangerous man in America’ by Richard Nixon, who was the most dangerous man in America, and a second psychologist who travelled to India, changed his name to Ram Dass, became an advocate of yoga and developed expressive aphasia as a consequence of a stroke.

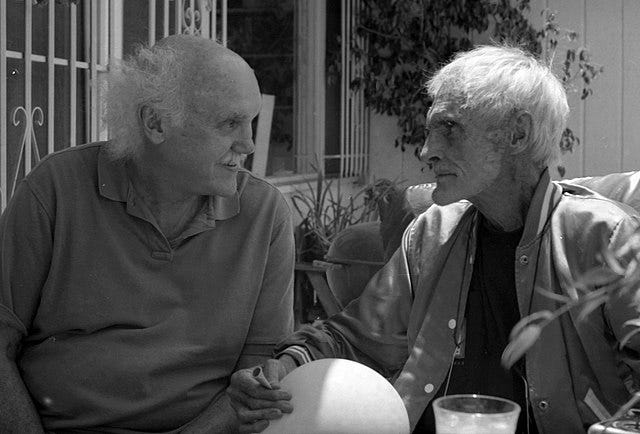

You can see Ram Dass and Timothy Leary in the picture below.

To tell the whole story would take at least one book. If you’d like a book, I can recommend one – an old one - called Storming Heaven: LSD & the American Dream, by Jay Stevens. For the time being, let’s focus our minds on the prison project.

Doctors Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert were working at Harvard's Department of Social Relations under the auspices of the Center for Research in Personality. These academic credentials are as impressive as they sound. Even so, the psychologists were hardly engaged in the kind of dry, repetitious inventory-and-factor-analysis work that the phrase ‘research in personality’ usually brings to mind. In the summer of 1960, Leary had made a life-altering visit to Mexico. There he became bemushroomed (and, yes, that really was the choice of vocabulary for an entire counter-culture):

‘Afterwards it was all he could talk about. How he had devolved back through millions of years until he had become a single solitary cell. And then returned, passing through the oceanic to the amphibian to the terrestrial, evolving out of the primordial slime into that smartest of smart monkeys, a Harvard professor.’[i]

Psilocybin was a compound synthesised from psilocybe mushrooms by Sandoz Chemicals. If the name ‘Sandoz’ rings a distant bell, it’s probably because that’s where the discoverer of LSD, Albert Hofmann, worked.[ii] Leary felt compelled to introduce psilocybin to his fellow smart monkeys. Or, at least, try to: unsurprisingly, nearly all of them refused. Or perhaps it was surprising. Certainly, Leary himself seemed to think so. The smart monkeys in question were professional psychologists, after all. Surely they ought to be at least a little bit interested by the contents of their own minds, or intrigued by the prospect of a guided tour of the unconscious. That, after all, was the promise psilocybin seemed to make. With more help from graduate students than his academic fellows, Leary – along with his friend, Richard Alpert - managed to set up one of the more notorious research programmes in psychology history: the Harvard Psilocybin Project.[iii]

As the Harvard University website is at pains to point out, ‘At the time of Leary and Alpert’s research at Harvard, neither LSD nor psilocybin were illegal substances in the United States’.[iv] There was no obvious reason to prevent the academics from going about their research.

About twenty to thirty other people quickly got involved. Most were junior figures at Harvard. The group would congregate at an old colonial house, fill in forms to document their emotions and expectations, swallow some pills, sit back, and wait. To use a word invented by the novelist Tom Robbins, they became ‘neuronauts’. To use a word that was soon to become a lot more popular, they had some claim to becoming the first ‘heads’.

One impressive study featured as many as 175 of these neuronauts. The experience, most agreed, taught them a great deal about themselves. The vast majority wanted to try psilocybin again.[v] ‘Research,’ claimed an enthusiastic Leary, ‘should be conducted with subjects rather than on subjects’.[vi] While he did the research, Alpert handled the inevitable bureaucratic red tape and schmoozing. They made an excellent partnership.

Excellent, maybe, but not universally popular. Revolutions, by definition, are divisive affairs - and some sort of revolution was evidently on its way. Leary started to assume a persona more messianic than scientific. The beat poet, Allen Ginsburg, materialised, ‘like a visitation from Leary’s personal unconscious’. Full of psilocybin, he walked naked into the researchers’ living-room. ‘I’ve come to preach love to the world,’ he told them. ‘We’re going to walk through the streets and teach people to stop hating’.[vii] How nice.

Perhaps encouraged by all this, Leary started dishing out psilocybin to various other hotshots. Jack Kerouac got some. So did Robert Lowell, William Burroughs, and Dizzy Gillespie… Kerouac’s experience alone is worth half a paragraph. ‘So what are you up to, Dr Leary?’ the charming fellow demanded, straight away, ‘running around with this communist faggot Ginsburg and your bag of pills?’ Not even Leary’s reliable pills could smooth the beat king’s abrasive edges. While Kerouac ‘continued to shout and guffaw with alcoholic exuberance’, Leary went to lie down for a bit. This was his first negative experience with psychedelics. Eventually, he got back up again, figuring, it seemed, that if you can’t beat the sullen, doomed, drink-soaked novelist, you might as well join him. ‘Walking on water wasn’t made in a day!’ Kerouac cried out, meaning who knows what. They stepped outside and played snowballs.[viii]

No wonder Aldous Huxley got straight on the phone. The gentle sage counselled caution. Make sure you look sciency, he advised the scientists, or the other scientists will try to end your Project. Too late – the Social Relations department was abuzz with rumours of jazz orchestras bemushroomed, headspace visits to Ancient Egypt, naked orgies at weekend retreats, an undergraduate ‘cult’[ix]… At first, Leary toiled to ensure every protocol was followed, every questionnaire completed – but the sheer quantity of work must have been overwhelming. Within four months, the Project had expanded the consciousness of more than 100 people. Three months later, it was up to 200.[x] Not even the most conscientious scientist could have hoped to keep up.

And Leary didn’t necessarily want to keep up. Surely, his work was far more important than anything else in global academia: it was ‘a social process that was far too powerful for us to control or more than dimly understand. A historical movement that would inevitably change man at the very center of his nature, his consciousness’.[xi] Eighty-five per cent of the subjects reported that ‘the experience was the most educational of their lives’.[xii] That compared favourably with psychoanalysis, in which the equivalent number was closer to thirty-five per cent. No wonder their disapproving faculty heard rumours that Leary and Alpert were constantly under the influence themselves.[xiii] If psilocybin was too good to keep to yourself, it was also too good to refuse.

But even a pair of maverick psychologists are still psychologists. No wonder, then, that they dreamt up a proper experiment to assess the wattage of psychedelic drugs. A call had recently come from the Massachusetts Department of Corrections, asking for psychology interns to come and work in prison. Leary invited prison officials for lunch at the Faculty Club. He made them an offer. He’d administer psilocybin-assisted group psychotherapy to a number of convicts (plus, after release, a support programme modelled on Alcoholics Anonymous). The rate of recidivism stood close to 70%.[xiv] Leary reckoned he could administer a short back and sides. was ‘an iron-clad, objective index of improvement’.[xv]

At last the scientists had a simple, elegant design with which to test their methods and theories. Having little or nothing to lose, the officials agreed to tidy away all the bureaucracy. You can imagine there must have been lots of it. Try proposing an experiment today in which you give drugs to convicts and see how quickly the red tape finds you.

That’s all for this week. Make sure you don’t miss next week’s exciting episode, in which we conclude the amazing tale of Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, and the Concord Prison Project. Is it the greatest story of the century? You be the judge! Here’s the link.

All pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit; partly so that you can check out anything that strikes you as particularly interesting.

[i] Stevens, Jay: Storming Heaven – LSD & the American Dream, Paladin, London, 1988, p193

[ii] Geiger HA, Wurst MG, Daniels RN: ‘DARK Classics in Chemical Neuroscience: Psilocybin’, ACS Chem Neuroscience, 2018 Oct 17; 9(10):2438-2447, available at: doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00186. Epub 2018 Jul 16. PMID: 29956917.

[iii] Harvard University Department of Psychology: ‘Timothy Leary’, available at Timothy Leary | Department of Psychology (harvard.edu)

[iv] Harvard University Department of Psychology, op cit.

[v] Stevens, Jay, op cit, p199

[vi] Gordon, N: ‘The hallucinogenic drug cult’, The Reporter, 29, 15 August 15 1963, pp. 35-43

[vii] Stevens, Jay, op cit, pp207-8

[viii] Leary, Timothy: Flashbacks – A personal & cultural history of an era, Tarcher Putnam, New York, 1990, pp64-67

[ix] Gordon, N, op cit

[x] Leary, Timothy, op cit, p71; 78

[xi] Timothy Leary, quoted in Stevens, Jay, op cit, p215

[xii] Leary, Timothy, op cit, p78

[xiii] Timothy Leary | Department of Psychology (harvard.edu)

[xiv] Leary, Timothy; Metzner, Ralph; Presnell, Madison; Weil, Gunther, Schwitzgebel, Ralph & Kinne, Sarah: ‘A New Behavior Change Program Using Psilocybin’, Psychotherapy Vol. 2, No. 2, July, 1965, pp. 61-72

[xv] op cit, p79

Eager to read the next newsletter. Exciting stuff. It is remarkable how practices change over time and how very challenging doing something like this would be in today-s world. I cant even imagine the IRB paperwork involved.

On the other hand we do seem to be engaging on some wacky stuff lately.

Harvard must have been a rather interesting place at that time, since shortly before Leary started his LSD research program another psychologist named Henry Murray conducted experiments on students in which he put emotional stress on the participants by verbal humuliation. One of these participants: the then 16 year old undergraduate in mathmatics Ted Kaszinsky, who later became known as the Unabomber. I am mentioning this since you mentioned him lately. Thank you very much for this essay.