Sunday e-mail 8th December: How to detect truth and lies

Forensic psychology; lie detectors; Statement Verification Analysis

Here’s today’s research question: How many heads do people have? You may know the answer - but can you prove it?

To see the difficulty, imagine you are a police officer. A stranger tells you they have been the victim of a crime. You have your doubts. How can you be sure whether the stranger is lying?

A better question may be: how can you be sure whether they are telling the truth? And the answer is, you can’t. You cannot, ultimately, be sure of very much at all in this world, not with complete certainty. That’s why our standard of courtroom proof is simply ‘beyond reasonable doubt’, rather than ‘with complete certainty’.

Judgments must be made on the basis of probability. To be completely certain that the stranger is lying is an impossibility. So, too, with truth-telling. The difficulty lies in proving that a statement is true. It is much easier to prove that one is false. Have you heard the expression ‘science proceeds by disproof’? That’s the reason. Scientists formulate an hypothesis that they think may be true. Then they invert it (in other words, they add the word ‘not’). They put together some research to test whether that inverted hypothesis is false.

Imagine you have set yourself the eccentric task that we started with: You want to prove that everyone in the world has just one head. How would you go about it?

It’s more difficult that you might think. Just wandering up and down your street, counting heads, isn’t going to work. No matter how long your street may be, it is going to provide a very small sample of the world population indeed. Perhaps, somewhere in the next town, lives a chap without the regular number of heads. By sticking to your own street, you’re going to miss them. Try going to the next town, then. Count the heads. Will you be able to answer the question then? Again, no. Maybe everyone you happen to see has just one head, but that doesn’t mean that there no exception exists anywhere.

Eventually you’ll have to count the heads of everyone in the world. Perhaps you manage this seemingly-impossible task. Everyone you’ve seen has one head! But now you need to start again because, by this time, more people have been born…

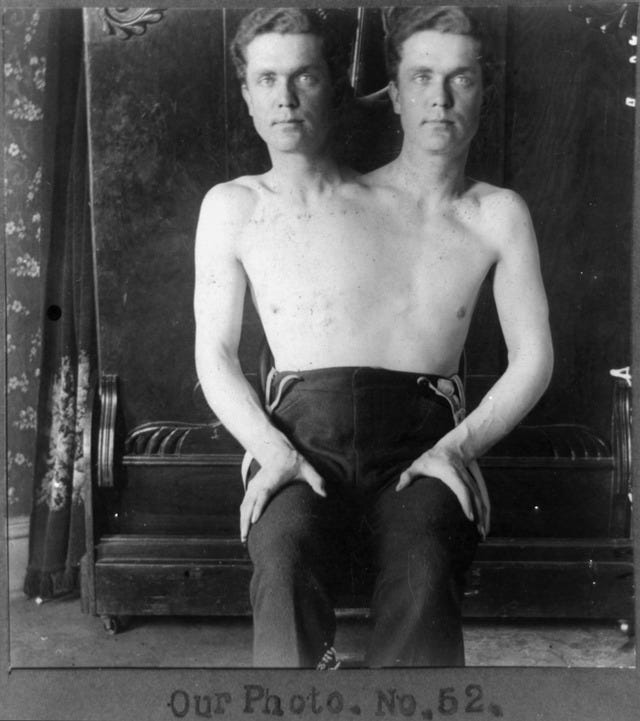

To prove a positive is all but impossible. But a negative? That’s a different matter. The first time you see someone with two heads, you know you were wrong to say that everyone had just one. You know it straight away, without doubt. The evidence is clear and unambiguous.

You want to know whether someone is telling you the truth? Start with the presumption that they’re not. Test that presumption against the evidence.

Maybe you’ve heard of the polygraph, or the computer voice stress analyser, or some of the other exotic equipment that police officers use in lie-detection. Now you know one reason why scientists are a bit sceptical of them. This week on the Crime & Psychology Substack, we’ll be introducing you to something different: not lie-detection but truth detection. Statement Verification Analysis (SVA) is exactly that: a technique, or set of techniques, to tell you how confident you can be in rejecting the hypothesis that someone is lying. It’s cutting-edge stuff. It’s new, it’s fascinating, and it’s right here on Crime & Psychology!

Did you notice that I used the word ‘we’ in the paragraph above? That’s because this week’s newsletter is the work of an outstanding Masters student, Arjen, who just completed his studies with an excellent theses on SVA. He’s an expert. And he’s very kindly agreed to visit the Substack and tell you everything you want to know about the topic.

Arjen did this work for no other reason than the kindness of his heart. I know you’re going to love his work. Count the days till Wednesday, Crime & Psychology fan!

All images courtesy of WikiMedia Commons.