Sunday e-mail 27th October: What we know we know about eyewitnesses...

...and why we know we know it

Every year, I finish my introductory Psychology class with a lecture about visual illusions and what they teach us about our perceptual system: gee-whiz material which leaves my students with the giddy, dizzy feeling that they’ve just come from the Psychology At The End of the Pier Show. Next year, maybe I’ll add in a little juggling and a sing-song.

Of course, it’s not all razzmatazz. It’s not all showbiz. There’s a serious purpose, too. When we learn how our eyes deceive us, we also learn how they work under other, more favourable circumstances. I say ‘eyes’ but really that is to misunderstand the process of visual perception, which occurs largely in the brain. The biggest illusion of all is that we see what’s ‘out there’, so to speak – that light rays enter our eyes, and stimulate cells in the retina, and this leads to some more-or-less straightforward representation in the brain of the objects in the world.

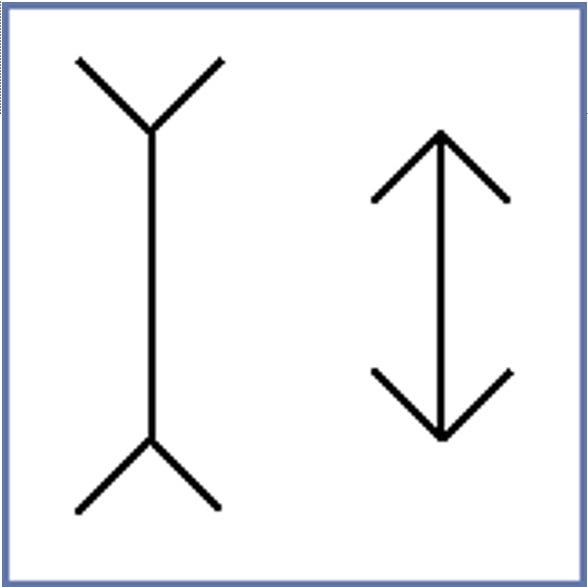

I say ‘more or less straightforward’, but it’s amazing how complex a straightforward process can be. Most of what we see when we look around the world is driven more by our brains’ pre-existing programs than by the real objects out there. It’s a consequence of our learning - our experiences and expectations. Take, for example, a rather simple illusion like the famous Mueller-Lyer, below:

The illusion doesn’t seem to work for everyone, so don’t worry if it leaves you puzzled. But for most people, the vertical line in the array on the left looks longer than the one in the array on the right. Measure the lines as many times as you like and convince yourself that they are indeed the same length. It won’t make the slightest difference. If one line starts off looking longer, it stubbornly persists in doing so. There is no cure.

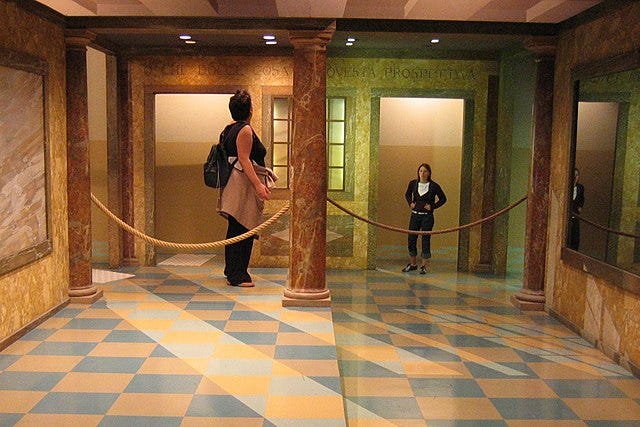

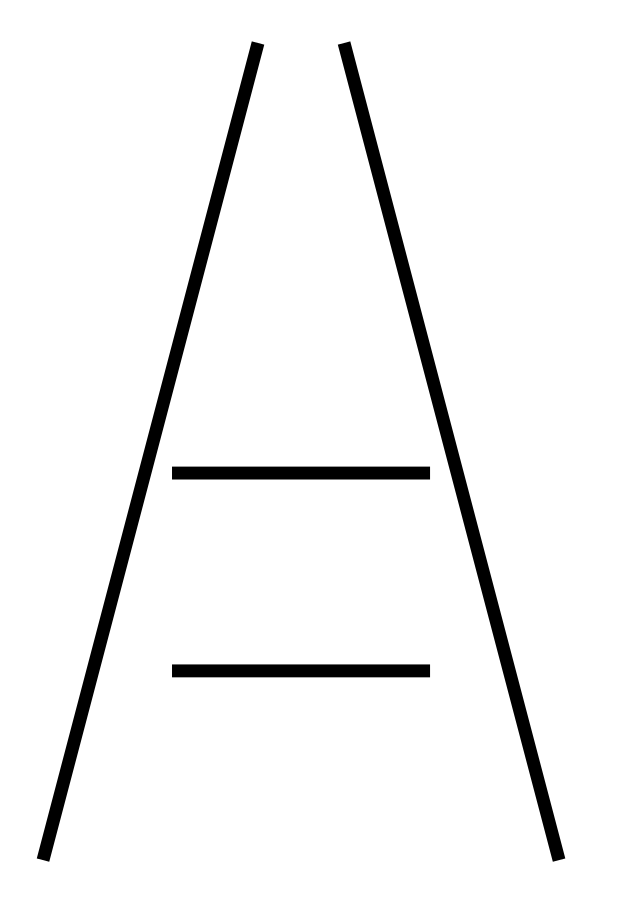

One explanation for the illusion is that the two arrays resemble corners in some imaginary architecture. The diagonal lines – we call them chevrons – make it look as if one corner is going away from you, into the screen, while the other comes out towards you. The vertical lines make identically-sized images on the retina. Your brain therefore makes a compromise: one line is closer; the other is more distant, yet they occupy the same space in the eye. One must therefore be longer than the other. What you end up perceiving is a compromise between what is truly ‘out there’ and what you have learnt about how the world – and architecture - work.

All of which makes certain academics suspicious. When I lectured on this topic last year, one of my colleagues was assigned the annual duty of sitting in for quality-assurance purposes. Afterwards, (once the usual rounds of applause were finished, the balloons had been released, the cake had been cut, and students’ tears – for the end of my course – had been dried,) he suggested that I might think about incorporating some material on the untrustworthy nature of knowledge.

After all, if you can’t believe your eyes, the reasoning went, you can trust nothing. If you can’t be sure of what you are looking at, you can’t be sure of anything else either. But contradictions lurk in any clever-sounding sentence like that.

If we can be sure of nothing, how can we be sure of that? That’s how I retorted, brilliantly, or wish I had. In fact, the science of perception is exactly that – science – and it does a fine job of telling us not only what we know, but what we know we know. Science is all about bringing clarity. In this case, it brings clarity precisely to our knowledge of perception. To claim that the science of perception itself gives us grounds to mistrust the science is not just to put the cart before the horse, but maybe to misunderstand the nature of carts and horses. Perhaps it is to put the cart on top of the horse, or in the next village, or give it to the horse as a birthday gift.

This week in Crime & Psychology we’ll be taking a look at the science of eyewitnessing. Eyewitnesses are the main source of evidence in about 20 – 25% of criminal cases, and the western world’s single most important cause of wrongful convictions. What do we know about eyewitnesses, what do we not know, and where might we be mistaken? That’s this week’s sizzling topic, Crime & Psychology fan. Be here on Wednesday to find out what’s hot and what’s not in the eyewitness world!

This week’s bullet list features some of my favourite visual illusions. Check them out below! No need to thank me – just see whether you can work out what the illusions are, and how we might explain them.

Don’t forget to join all the other cool kids on Wednesday! It’s not long to wait!

All images courtesy of WikiMedia Commons

Great read! I used to start my middle and high school lessons with optical illusions, sound ones (those songs played backwards with "matching" lyrics, and more. In short, on day 1 the argument was your senses and your intuitions can easily lead you astray. Science, while totally imperfect, and in many ways reflecting social concerns, mores, prejudices, is at least a systematic attempt to discipline our senses -- to try and avoid misconstruing reality and to try avoid believing in illusions. It was a student favorite.

Then we would march on with science class... with occasional tangents on how we do think we know...

Marvellous. Thanks Jason.