Unsettled. The bandit has felt unsettled today. A question has been on his mind. He’s an unreflective sort and this isn’t like him. The bandit can barely recognise himself.

He has come home from work. We can picture him closing the front door softly behind him. ‘Honey, I’m home!’ He unlaces mud-caked boots and puts them into the rack. His dog certainly seems to know who he is.

Mrs Bandit does, too. That’s what the neighbours call her, by the way, although her real name might be, I don’t know, Deirdre. She hastens to the entrance vestibule where she gives Mr Bandit a welcome-home hug.

‘Hard day, dear?’ she probably asks.

The bandit is monosyllabic in reply but she does not mind that. He often is. There is nothing yet to worry her. She’s used to her husband’s weariness; she’s used to his aching muscles and his silence. She knows the long hours he puts in. He fights for her. He fights for all the poor people and peasants, the dispossessed. Deirdre helps him off with his bandoliers. They are terribly heavy but not as heavy as she pretends. She offers him a solicitous shoulder-rub, but all he wants is his regular early-evening beer.

Beer? Is that right? What do bandits drink, anyway? If he were a pirate, I’d have his wife offer him a glass of rumfustian. If you’re a regular reader of our Dictionary of Crime, you’ll know that rumfustian was a hot drink beloved of buccaneers. The ingredients included gin, sherry, eggs, sugar, cinnamon, and anything else that happened to be lying around in the ship’s galley. Sounds like a bother to make. Let’s have Deirdre bring her husband a flagon of ale, then. That sounds appropriate.

Entering the drawing-room, Deirdre is surprised to find Mr Bandit looking into the mirror. Not at the mirror: into it. It is at this moment she begins to grow concerned. He’s a bandit. What business does he have with introspection?

‘Was it a hard day, dear?’

‘Aye’ he says. ‘’Twas a hard day all right.’ How do bandits talk? I have no idea. This one sounds more like a pirate to me.

‘Sit down, dear. Drink this nice flagon of ale.’

‘Is there no rumfustian?’ asks the bandit.

‘Gosh, I’m afraid we’re out of rumfustian,’ says Deirdre. ‘We drank the last of it at the weekend, when the Petersons came over. Would you like me to nip out and get some more?’

‘Arrr, no, lass,’ says the bandit. ‘I’ll just drink the ale.’

‘Was it a terribly busy afternoon?’

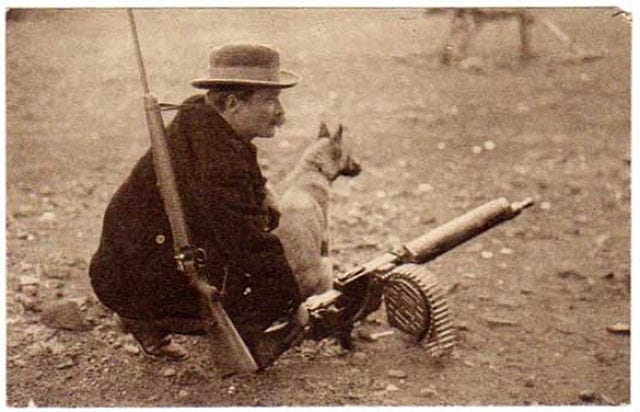

‘Aye…’ The bandit sips at his flagon; wipes foam off his moustache. It’s a splendid, fearsome moustache, but even so he looks very contemplative. ‘All stealing from the rich,’ he says. ‘No time for giving to the poor.’

‘Oh, the same old story… You poor dear. Perhaps tomorrow you’ll have better luck. Would you like me to run you a bath?’

The bandit does not reply. He has taken a flintlock from his belt and is handling it as if it were a puzzle he might solve. ‘All stealing from the rich…’ he repeats.

‘What you need is a nice hot bath.’

‘Lass!’ The bandit stops his wife before she can leave the room. ‘Lass, tell me one thing. Tell me this. Am I…am I really a bandit?’

The woman known as Mrs Bandit is surprised. She would be. ‘Of course you’re really a bandit. Why wouldn’t you be?’

‘I’m not just a robber or a mugger am I?’

‘Everyone says you’re a bandit and that’s what counts'.’

‘Is that what counts, is it? What everyone says? Might everyone not be wrong, me hearty?’

‘Oh, honey,’ Dierdre says. She’s just starting to understand just how concerned she ought to be. ‘I would never have married a common-or-garden robber or mugger, you can be sure of that. Ever since I was a little girl, my heart was set on a bandit. So you must be a bandit.’

‘Must I? Arrr. Yet today was the first time as ever I thought of it, me hearty.’ He looks down the business end of the flintlock. Is his soul as dark as the inside of the barrel? ‘Per’aps I’m no bandit after all. Per’aps I’m just a land pirate.’

‘A land pirate?’ Deirdre is shocked. ‘A land pirate? Of all the awful, terrible things. Whoever has been putting such ideas into your head? Now, you finish your flagon while I run you a nice hot bath to soak all these silly ideas out of your head. A land pirate, really, I never heard the like…’

‘Could it be that I’m only a bandit cause I think I am?’

‘I don’t want to listen to any more of this nonsense, dear.’

‘What is it that makes a bandit a bandit?’

‘You’re just being silly now.’

The bandit is scared of only one person in all the world. He knows better than to pursue the discussion. Yet he remains unsure. What exactly is the difference between, say, the bandit he thinks he is and the mugger he fears he may actually be? What is in a word?

The bandit drinks the rest of his ale – he probably quaffs it, in fact, that’s what bandits generally do – and steps to the window. His image reproduces itself faintly on the glass, the ghost of a bandit perhaps. He stares into the middle distance. A great expanse of arable land, two or three downtrodden peasants labouring in the fields. In the distance, the bandit can hear a tractor.

His wife shouts down the stairs. ‘Do you want bubble bath, dear?’

Of course he’s a bandit! The view from the window tells him so. The lifestyle he can see out there – the lifestyle his grandparents’ grandparents would have seen – tells him so. It is threat from outside that conjures a bandit from the very soil. Blame those city-people, with their constant demands for change, roads, rent money, holiday cottages… The bandit’s ‘crimes’ break nothing but the rich man’s laws. That’s what he would tell you, anyway, if you asked. If there were no peasants, if there were no downtrodden classes, why then he’d have taken up a different profession. He’d probably have become a labourer himself.

Meanwhile, there’s plunder to count. Another dull task. The bandit is looking forward to just one thing in life…Wednesday! Wednesday, he knows, is the day when the Crime & Psychology newsletter always appears, regular, reliable, confident as clockwork. He knows, too, that this Wednesday will be special. The newsletter is going to be all about bandits –- where they come from, what they are, and why. The bandit is like you – he can’t wait to read it. He is very excited and you should be, too.

See you then, Crime & Psychology fan! Meanwhile, please bang a blue button below. It really does make a difference.

This week’s brilliant bullet list is blatantly bandit-based:

Marxist historians have argued that certain types of crime are the predictable outcome of given political and economic circumstances. The historian, Eric Hobsbawm, wrote a classic books called Bandits, which illustrated the point.

The word ’bandit’ does not apply exclusively to moustache-wearing representatives of the downtrodden underclass. It is used colloquially to refer to a minor criminal who specialises in certain types of job. A ‘bag bandit’ is a mugger, for instance, and a ‘brass bandit’ follows soldiers into action to pick up the shell casings. The dictionary also gives us ‘arse bandits’ and ‘snatch bandits’, but there’s no need to go into that here.

Want to meet a modern-day bandit? The literature seems to indicate that you should visit Sardinia, where the balenta is much admired. I am sceptical, though, since this seemed to be news to the last Sardinian person I met.

The term is a relative newcomer to the English language, with its first recorded use being in 1776. It derives from the German practice, bamnan, which referred to the practice of banning criminals - or, literally, outlawing them.

Back in the day, there was a chocolate bar in the UK called Bandit (‘You can stand it with Bandit’). I didn’t trust my memory on this until I looked it up. I thought it might be an example of the Mandela Effect. And then, growing increasingly worried about my own state of mind, I began to wonder whether there really was such a thing as the Mandela Effect, or whether I’d imagined it.