On Wednesday, the Crime & Psychology newsletter completes the story we began last week. Prepare yourself to learn more about the serial killer, Peter Kürten and his unpleasant end.

‘Unpleasant’ is a mild word to use. Kürten was the kind of serial killer that other serial killers cross the road to avoid. Not only did he murder the most vulnerable of strangers, but he did so promiscuously, horribly, and sadistically. Their deaths gratified him and excited him sexually. He experienced no remorse and had no conscience. ‘The Vampire of Düsseldorf’, has also been called ‘The Monster’. You can imagine why.

A person who is capable of crimes like Kürten’s seems barely to qualify as a human being at all. It is as if they skipped a bit of the assembly line: some vitally important component was left out. They seem to be something other; something altogether different from ourselves. We commonly use the word ‘monster’ to refer to the worst criminals we know. There have been far too many of them. A moment’s thought gives me the ‘London Monster’ (Renwick Williams), the Monster of Juárez (possibly Abdul Latif Sharif), the Soham Monster (Ian Huntley), the Monster of Florence (Il Mostro di Firenze), the Monster of Cannock Chase (Raymond Leslie Morris) and the Monster of the Andes. The well-known 2003 film about Aileen Wournos is called Monster. So is a Netflix anthology series about serial killers. In 2019, Oxford Academic published a book called Terrorists as Monsters. I am tempted to point out that Shamina Begum’s podcast is called ‘I Am Not a Monster’ - but I shan’t, because I suspect I’ve made my point.

The monster – writes one philosopher – ‘is the inverse or outside of what is acceptably human’.

All of this raises an interesting question: Why exactly are monsters so interesting? What makes them that way? Surely it isn’t just morbid fascination (and, even if it were, why? Why are we ‘morbidly fascinated’?) Do we really just want to ‘understand the monsters better’, as so many true-crime readers claim? Well, maybe, but I suspect that’s not the whole story.

Perhaps the answer is not too far to seek. In a PREVIOUS newsletter, I mentioned Carl Jung’s belief that the only reliable path to goodness is through evil. To learn about evil is in itself a positive good. It is commendable. By comprehending evil, we give ourselves the opportunity to become good. It is in encountering the evil, the nasty, and the criminal that we feel the presence of the decent, the good, and the law-abiding. We know which side we’re on.

Wrote the philosopher, Richard Kearny, ‘monsters are our others par excellence. Without them we know not what we are’. The Early Modern witchfinders had a saying: Nullus deus sine diabolo. It means ‘There is no God without the devil’.

This week’s fabulous bullet list features fascinating facts about – what else?:

· From the 5th century, and well into the Middle Ages, people spoke of the Monstrous Races: human, but not as we knew it. Their bodies were jack-straw job-lots, confused as the earliest western travellers themselves became as they ventured past the borders of their mostly-blank maps. Sciopods, for instance, possessed just one giant foot, which they used as a parasol. The strange beings who inhabited alien lands could not be considered fully human: they were far too far from civilisation. You can see the Monstrous Races on he outer edge of the map, below:

· That word, monster, has revealing origins. It comes ultimately from the verb moneo, which means to remind, warn, foretell. Monsters exist in order to remind us who we need to be, warn us to cleave to the path of righteousness, and foretell our fate if we fail.

· The sixteenth century saw the beginnings of what you or I might recognise as modern science. It created as much disturbance as it dispelled. Copernicus, for instance, showed the Earth was not the centre of the universe. There was a rash of monstrous births – or, at least, a rash of reports of monstrous births. The Monster of Ravenna, for instance, appeared to be an incarnation of Early Modern angst, what with its human torso, birds’ wings, and feet in the shape of claws.

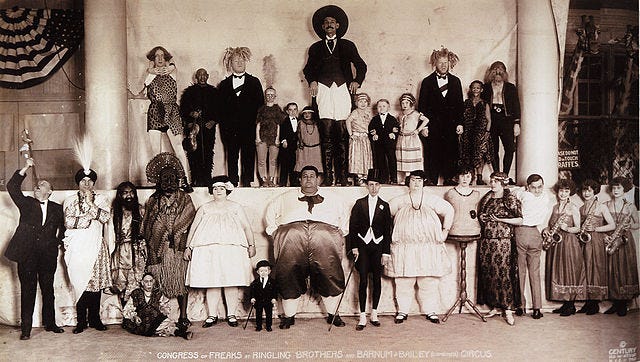

· Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century travelling shows and fairs incorporated more and more human ‘freaks’. A ‘freke’ is defined as a ‘remarkable creature or being’. PT Barnum opened his American Museum in 1841, and, as any viewer of the film The Greatest Showman can tell you, it was both extremely popular and heavily invested in ‘freaks’. (See Ringling Brothers, above,too.) A nineteenth-century person no longer had to trvael long distances to view ‘the Monstrous Races’. All they needed was the price of a ticket.

· As we saw above, it is criminals like serial killers and terrorists who attract the label these days. The post-modern monster is even closer to home now. These criminals are especially frightening owing to their refusal to look like monsters. This may explain why no news report of an atrocity is complete without photographs, or, preferably, video. Like an antelope staring at a lion, don’t you feel that low-level compulsion to know just what your enemies look like?

More on Wednesday, Crime & Psychology fan!

I've been investigating the Jeremy Bamber case for the past 4 years. The 1980's media (with the help of the police) helped shaped the public perception of him as a "monster" - I've got to know him very well and not only am I convinced he's the victim of a miscarriage of justice but that the media played a huge part in the publics wider perception of him. A good story for you to look at.

Great read ! These two columns have been extremely well written and quite disturbing. I do think you are onto something with regards to why people find such other people interesting. I suspect at one time or another many people have entertained thoughts of breaking things in bashes of anger and may have thought ill of others... in some way seeing such extreme behavior may make more "acceptable" thoughts well tolerable.