JACK & NORMAN; WILLIAM AND BEN

Fiction; the non-fiction novel; prison; capital punishment; murder; stabbing; kidnap; rape; rehabilitation

Today’s story is about couples and counterparts, twins and pairs, dyads and duplicates. It features two long-term prisoners, two nasty crimes, and two Pulitzer-Prize winning books, one each by a pair of Great American Novelists. Sounds exciting? Let’s go…

Norman Mailer may have been the most divisive and pugnacious writer his country ever produced. Early in 1978, thirty argumentative years into his literary life, Mailer received a letter from a ghost. It arrived while he was writing The Executioner’s Song, which was a non-fiction novel about the life of Gary Gilmore. Or perhaps one should say, about his death.

Only one year earlier, the death penalty had been on hiatus. There had been no executions in the United States since 1973. While a death sentence might be pronounced in court, it did not really mean what it said. Gary Gilmore, though, insisted that it should. ‘You sentenced me to die,’ he supposedly told his judge. ‘Unless it’s a joke or something, I want to go ahead and do it.’[i]

Gilmore eventually got his way. He was shot by firing squad in the first month of 1977.

His ghost appeared in the form of Jack Henry Abbott. He and Gilmore were not dissimilar: a pair of career convicts just four years apart in age, who’d entered adult prison at more or less the same time. They had even been in two prisons together. Abbott claimed to have known Gilmore a little. He might be able to give Mailer unique insights into his subject’s personality.

Mailer himself had served a minor seventeen-day stretch at Bellevue Hospital in 1960, after stabbing his wife. Abbott had stabbed someone, too: a fellow inmate, after he was initially sentenced for burglary. By contrast with Mailer, his punishment had been a lifetime in prison. Gilmore was the product of a system that Abbott knew only too intimately. No celebrated author – however notorious – could possibly imagine the ‘inner rage and paranoia brought on by a lifetime behind bars.’[ii] Mailer found himself eager for Abbott’s guidance

The great writer was impressed in more ways than one. Reading Abbott’s prose, he ‘felt all the awe one knows before a phenomenon’[iii]. Soon Mailer and Abbott were exchanging letters every second day. Abbott took his own half of the correspondence and turned it into a manuscript. He called it In the Belly of the Beast. Mailer sent the manuscript to Random House, who offered $12,500 for it. As long ago as 1980, it was a truly significant advance.

When Abbott came before his parole board, he was able to present himself as a reformed man, a triumph of rehabilitation, a veritable advertisement for himself and for the penal system. Here he was holding all the cards: a contract with a major publisher; a famous writer for a sponsor; even a job to go to (Mailer offered to pay him as a researcher). We can imagine Abbott blinking as he came out into the world – partly owing to the sudden sunlight, partly owing to simple disbelief. The ex-con found himself abruptly equipped with famous friends, party invitations, excellent reviews, even a little cash. Nothing could go wrong.

Everything went wrong. Two weeks after his book appeared, Abbott visited a restaurant in Greenwich Village. There he stabbed to death a Cuban man named Richard Adan. Adan was an actor and dancer, not quite famous, but certainly of some renown. His family owned the restaurant and he’d been working that night as a waiter. Abbott went on the run: Chicago, Texas, and finally Louisiana, where he was captured. By January 1982 he was on trial again.

The courtroom sounds like a catwalk of radical chic. The Village Voice dropped in. So did The Soho News. Have you met Christopher Walken? Oh, and I must introduce you to Susan Sarandon. Mailer testified. Journalists questioned him on the courthouse steps. ‘What will happen if Jack Abbott gets out of jail and kills again?’ asked the New York Times. Mailer said he ‘would take that gamble…I am willing to gamble with certain elements of society to save that man’s life’. ‘What elements are you willing to gamble with?’ another reporter demanded, angrily. ‘Cubans? Waiters? What?’ Mailer had little in the way of an answer.[iv]

On Mailer’s performance, opinions were divided. ‘He isn’t self-protective. He doesn’t lie. He’s honest – too honest maybe.’ So said one observer. ‘Mailer, you’re full of shit!’ shouted another.[v]

Here is Detective William Majeski, who investigated the stabbing: ‘Abbott’s whole personality is based on the premise of prison society, and in his mind he was justified in killing Adan because any time you’re posed with a threat or an imagined threat in prison you eliminate it – you eliminate it, because if you only wound or maim a guy he’ll come back and kill you. That’s Abbott’s whole inner structure, his moral standard. It’s established over twenty-five years in prison and you can’t take a lifetime of that and suddenly adjust it to society’[vi].

Mailer couldn’t say he hadn’t been warned. His own wife, Norris Church Mailer, had told him, ‘You wrote the book about Gilmore – didn’t you learn anything? It’s not gonna work, these guys don’t change’. Even Abbott himself had said, ‘[T]he odds are now overwhelming that I may not be as other men’[vii].

One person who refused to condemn Mailer was his fellow novelist, William Styron[viii]. ‘My heart goes out to him,’ Styron said. ‘I have an Abbott in my life’[ix].

Styron and Mailer – the two novelists shared a tangled history. Both were part of that great generation of post-war Americans that included James Baldwin, Saul Bellow, Truman Capote and others. It might be a fractious and ill-sorted cohort, but it was united by the bonds of talent that each recognised in his fellows. They were so much of a ‘club’, they practically had a members’ list. Nothing could change that, not even a bitter argument ‘about wives’[x], after which grumpy Mailer refused to acknowledge Styron when they passed on the street. He even challenged his rival to a fistfight. ‘I expect to stomp out of you a fat amount of your yellow and treacherous shit’ wrote Mailer to his former friend[xi].

No surprise, the two men had not spoken for some time. It reflects well on Styron, then, that he was willing to stand up for Mailer. Indeed, one of Mailer’s biographers comments that their reconciliation was the only happy outcome of this whole affair[xii].

Styron too was a figure of controversy. In the late 1940s, he had decided to write about the Southern slave rebellion led by Nat Turner in 1831. He published his novel to what we might call mixed reviews. Some argued that Styron had no business writing such a character – particularly one who lusted after white women. Neither did he have any business writing about saintly white slave-owners. Ten black American writers teamed up to compose an entire book of criticism.

If there was anger, there was also acclaim. The Confessions of Nat Turner, like The Executioner’s Song, won its author a Pulitzer Prize.

Writing it had not been easy. Styron had difficulty finding the appropriate voice for his creation. Like Mailer struggling to imagine the mindset induced by a lifetime in prison, Styron struggled to imagine the mindset induced by a lifetime of slavery[xiii]. His problem remained intractable until the early 1960s. That was when Styron became mixed up in his own criminal case

In 1957, one Benjamin Reid had beaten a woman to death with a hammer. It seemed to be an attempted robbery. The victim was known to carry cash around in tempting quantities. But Reid had panicked. He fled without a cent. Police tracked him down quickly. Indeed, the killer ‘seemed rather relieved to be caught’[xiv]. Later that year, he was sentenced to death.

Esquire magazine had offered Styron - the ‘unabashed advocate of abolition’ - a deal to write an essay or series of essays about almost anything he chose. While he was reading up on capital punishment, Styron came across a newspaper article about Death-Row prisoner Benjamin Reid. He had a subject.

Redemption was a concept high in Styron’s mind. The ideal had been instilled by his religious upbringing. The concept is not so far removed, of course, from that of rehabilitation, which is one of the goals of America’s criminal justice system.

There was a reprieve. Part of the credit for saving Reid’s life goes to Styron, and the essay he chose to write. As soon as he found himself in General Population, Reid flowered. He demonstrated ‘qualities of character, of will, and, above all, of intelligence that defied everyone’s imagination’. He seemed to be a ‘triumph of faith over adversity’[xv].

It certainly looked like a story of redemption, but, as Styron later wrote, ‘[I]n the terrible cosmos of our prison system, and among the disadvantaged and the broken who are forced to dwell there, there are seldom any happy endings’[xvi].

In 1970, Reid became eligible for parole. Would Styron be willing to let the ex-con stay in his own home, while the board found a place for him at college? Styron was delighted to say yes.

With just a few weeks to go, Reid escaped. Police chased him with dogs but lost the trail. After a night in the woods, Reid made a weapon from a car radio antenna. He broke into a house where he kidnapped three children and a woman. He forced the woman to spend a day driving, apparently without purpose, up and down the Connecticut River Valley. He raped her. Later, he was spotted by a prison official as he got onto a bus headed for New York. There was another trial. Reid’s sentence was ten to fifteen years.

Styron’s theory is that a man who had spent all his adult years in prison knew that he was could not stand freedom and wanted to ensure he’d be returned to the only life he understood.

Jack Henry Abbott and Benjamin Reid: a novelist might choose to stay away from material like this. The similarities are almost too glaring. ‘[B]roken homes, poverty, neglect, abuse, foster parents, and the loathsome taste of incarceration at an early age. And years and years of the inhumanity of prison life. It is hardly possible to feel anything but revulsion for both Reid’s and Abbott’s ultimate crimes, but it is plain that each crime in its own way was the result of perceptions wrenched and warped by the monstrous abnormality of long imprisonment.’[xvii]

‘[D]angerousness is situational,’[xviii] writes the well-known FBI profiler, John Douglas (he of Mindhunter fame). He is making a plea to criminologists and forensic psychologists to recognise that when a criminal is in prison, with its ordered and predictable environment, he may well be worthy of your trust. But let him escape into your suburban home, let him get into a disagreement with a waiter at a Greenwich Village restaurant, and…well, we have seen what can happen.

‘The best predictor of future behavior, or future violent acting out, is a past history of violence’, writes the Behavioral Science instructor Al Brantley[xix]. You may well resent all those tax dollars we spend on our prisons as it is. Many people do. But until prison systems improve, we can hardly expect anyone who leaves them to be better than they were when they went in. Rehabilitation – let alone the redemption that Styron dreamt of – is going to remain unlikely.

That’s all we have time for in this newsletter. I hope you found the story interesting. If so, please bash a blue button below.

Alternatively, you can buy me a coffee!. Go on: I like coffee.

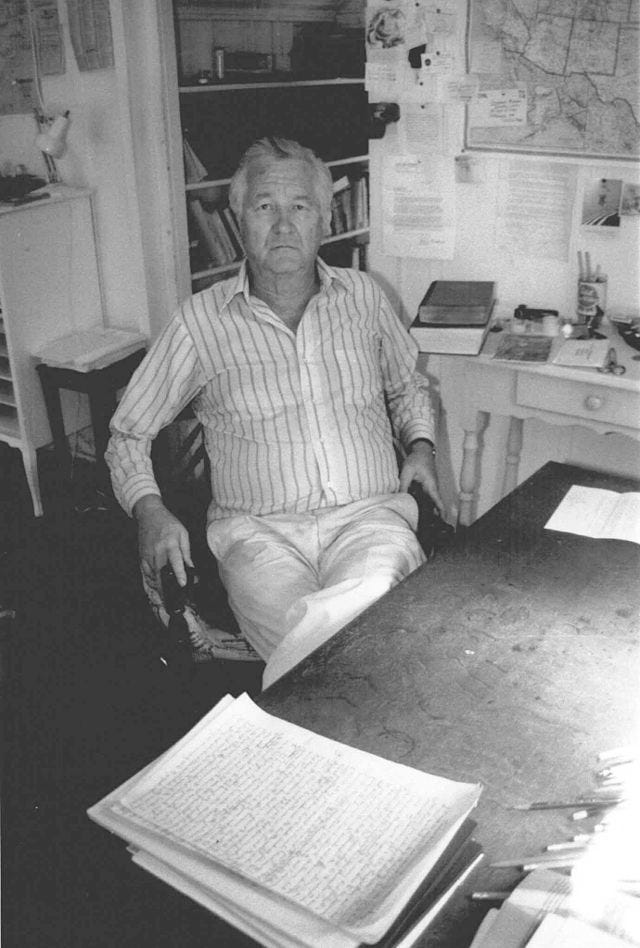

Mailer and Styron pictures courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit but also so you can chase up anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Gary Gilmore, cited in Loving, Jerome: Jack & Norman – A state-raised convict & the legacy of Norman Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song, Thomas Dunne Books, New York, 2017, p1

[ii] Loving, Jerome, op cit, p9

[iii] Norman Mailer, quoted in Bradford, Richard: Tough Guy – The life of Norman Mailer, Bloomsbury Caravel, London, 2023, p245

[iv] Bradford, Richard, op cit, p244

[v] Liz Smith & Thomas Hanrahan, quoted in Manso, Peter: Mailer – His life & times, Penguin, New York, 1985, p645

[vi] Detective William Majeski, quoted in Manso, Peter, op cit, p635

[vii] Norris Church Mailer & Jack Henry Abbott quoted in Manso, Peter, op cit, p625; 623

[viii] Styron, William: This Quiet Dust & other writings, Random House, 1982, p140

[ix] William Styron, quoted in Lennon, J Michael: Norman Mailer – A Double Life, Simon & Schuster UK Ltd, London, 2013, p566

[x] Mickey Knox, quoted in Manso, Peter, op cit, p249

[xi] Norman Mailer, quoted in Bradford, Richard, op cit, p133

[xii] Lennon, J Michael, op cit, p566

[xiii] Coltrane, Robert: ‘The unity of This Quiet Dust’, PLL, 88, 1983, p482

[xiv] Styron, William, op cit, p113

[xv] Styron, William, op cit, p138

[xvi] Styron, William, op cit, p111

[xvii] Styron, William, op cit, p140

[xviii] Douglas, John & Olshaker, Mark: Mindhunter – Inside the FBI elite serial crime unit, Arrow Books, London, 2017, p373 (italics in original)

[xix] Al Brantley, quoted in Douglas, John & Olshaker, Mark, op cit, p373

Powerful and engaging column on such an important matter. For post people prison is not for life, and hence we need to think carefully about how to improve these systems to reduce recidivism and to prevent prisoners from becoming worse. Really challenging to think about people who get convicted for a long time given the crimes they committed. short sentences seem problematic, but so do other options. We have heard / read some things about Norway and other systems that appear to achieve much lower rates of reoffending. We wrote a first pass on some of this issues: https://curingcrime.substack.com/p/recidivism-trying-to-rehabilitate-prisoners-91fd4a7b5f5e