'HAMMER OF THE WITCHES'

Witchcraft; demonic copulation; teleology; heresy; Apocalypse; torture; superstition; reasoning

For centuries, witches had been no great problem. The Vatican blandly declared that they didn’t exist. Catholics were not allowed to believe in them. And then the orthodoxy reared round and doubled back. Suddenly, Catholics weren’t just allowed to believe in witches, but were positively required to. They had to believe in demons, too. Let’s see how this happened, and what it meant for the very earliest days, for the pre-history of criminology.

We shall start with an enigmatic character named Thomas Aquinas. He was one of the most important thinkers in the philosophy known as Scholasticism, which dominated Western thinking throughout the medieval period. His ideas have affected the lives of countless generations, Catholic and otherwise. And yet, for all his fame, Aquinas left rather little of himself behind. Here’s what we know:

He was born early in the thirteenth century (probably 1225 or 1227) in the Kingdom of Naples. His was a good family, full of counts and descendants of Holy Roman Emperors. Yet, as far as Aquinas was concerned, Aristotle was more important than any of them. ‘The Philosopher’ had such an influence on the young man, he decided to go to Rome and become a monk. His brothers, unimpressed, held him hostage for two years. Hardly the most merciless of kidnappers, they used every temptation – including a selection of prostitutes - to seduce him away from the spiritual path. It didn’t work. Eventually, the story has it, Thomas escaped from his window in a basket - lowering himself down like a baguette in Montmartre - and ran off to join the Dominicans, who allowed him to experiment with a compound of Aristotle and Christ.

Shiny ideas won Aquinas chairs in Theology at grand universities throughout Europe. His reputation grew steadily. Unfortunately, it wasn’t the only thing. Aquinas became so nearly spherical, his portraits make him look like a hot-air balloon wrapped in a sheet. In later life, he needed a special desk for his giant girth. Sitting at just such a desk, the egg-shaped monk hatched his great work, Summa Contra Gentiles.

The book was intended to prove the existence of God. Central to its argument was the study of purpose - known as ‘teleology’. ‘The Philosopher’ had said that purpose was vital to we could understand something only by knowing its purpose. An eye, for example, has the purpose of seeing; an acorn has the purpose of becoming a tree. Human beings have the purpose of helping God out with His plan.

A millennium of Catholics had learnt that demons did not exist. Now Aquinas told them they’d been wrong. Those non-existent beings were practically everywhere, and far more dangerous than they had any right to be. Their purpose was to get human feet onto the primrose path, and human souls into the place to which it led. Witches, meanwhile, were simply those gullible souls who’d fallen for their tricks.[i]

How did we know demons were real? They had sex with human beings. So Aquinas reckoned.[ii] We’ll see the significance of that very soon.

Aquinas stopped writing part-way through another book, and died before returning to it. If the flesh perished, the philosophy proved immortal. It was just what Catholicism needed, because it helped fend off doubt. Doubt, after all, was heretical: it could take you to Hell! Catholics must not – must not – fall prey to it. Thomism must not be wrong. It must remain a strong straight stick for wavering Catholics to lean on.

A stick was just what they needed. European thought was the very definition of discomfiture. The continent ‘saw itself beset by schismatics, Turks, apostates, heretics, idolaters, and even the Antichrist’[iii]. Look at the Great Famine (1315-22), the Black Death (1347-52), the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453)… And don’t even mention the Papal Schism – two Popes, no less, each claiming to speak on God’s behalf. No one could blame a person for worrying.

Millenarianism became common: the belief that Apocalypse was imminent. But Apocalypse didn’t come. It kept on not coming. This was widely regarded as problematic.

Discomfiting times produce good things and bad: the terrible beauty of the Renaissance, for instance. Italian culture in particular bloomed, more glorious than anything since classical times. Classical times, in fact, were all the rage. Just take a look at the Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510), and the architecture of brand-spanking-new Catholic churches.[iv]

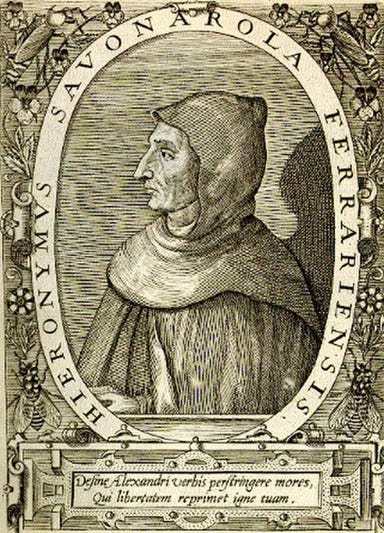

If it was Italy that gave the Renaissance to Europe, it was Florence that gave it to Italy. Florentines practically invented the modern world. Yet at the height of its brilliance, Florence was hypnotised by the mad monk, Girolamo Savonarola (1452-98).

Savonarola decided to transmogrify the rose city into a ‘Christian republic’, in which death would be the punishment for everything Savonarola himself didn’t approve of. It would be quicker to list the things he did approve of. The list would start (and possibly finish) with himself. His famous Bonfire of the Vanities was built from the belongings of sinful Florentine followers. Savonarola incinerated books, games, paintings, musical instruments, and just about everything else. He was the most dangerous sort of villain – the kind who sees a hero in the mirror, or would do, if he hadn’t burnt the mirrors, too.

At length, the Pope had enough. Savonarola too was burnt.

He was among the first of many.

In 1424, a Catalan count had a group of local heretics burnt as witches. Two women were executed for turning themselves into cats and drinking blood. Within four years, the traditional European witch had made the scene.[v] The craze had begun.

All of this was part of a systematic attempt to prove once and for all that God was good, the Bible true, and Scholasticism a trusty crutch. If we want to understand the witch-craze, we need to understand this vital point. We often think of the witch-craze as being a result of superstition. That’s not quite true. Superstitious belief did not drive anyone to become a witch-finder. Belief, rather, is what the witch-finders wanted. It’s what they were after.

Christians sought nothing less than confidence in God and their Church. If a cosmic battle was going on, naturally they wanted to be on the winning side. They wanted to be sure they were. Nothing would do but complete vindication, unquestionable proof.

Here’s the chain of logic: Aquinas claimed that witches had supernatural powers, which they owed to demons. So, if witches existed, demons must exist, too. If demons existed, there could be no question about their master, Satan. And if he existed, only a fool would doubt his counterpart. God’s Church was self-evidently on the right side. QED.

This left just one practical problem – to prove that witches possessed supernatural powers. How to do so? Make them confess! Ragnarök was here, Götterdämmerung, the Twilight of the Gods. Any means were justified, even torture.

Let’s not go into the details. There are plenty of sources for that. Instead, let’s point out that any fractured organisation can strengthen itself by discovering an enemy. To share an enemy is to forget our own differences. An Enemy is even better: one with a capital letter. If Catholicism was fractured, it was partly because of Protestantism, an infant religion with, so far, an infant’s strength. Protestantism, too, could strengthen itself with an Enemy. And then there was that other great new invention, the modern State. If the State didn’t have Enemies, what was the point? Witches were perfect all round.

The Hammer of the Witches

Pope Innocent VIII (1432-1492) kept hearing about Middle-Europeans who were copulating with demons. He commissioned a report (well, you would). Its authors were Heinrich Kramer and Jacob Sprenger. Their report was called Malleus Maleficarum, which means Hammer of the Witches. It’s the most important book ever written about witchcraft.

Kramer, chief author, had fallen into stardust. His career to date had been, let’s say, mediocre. As an Inquisitor, he’d been noted more for zeal than talent. Frankly, Kramer comes across as a bit of a nerd, with the nerd’s facility for alienating those around him. He just wouldn’t stop talking about witches. His employers were sceptical. They tutted, fussed and, doubtless, told him to get real. Exasperated Kramer could do nothing but, one imagines, hop up and down excitedly. And then, suddenly, there was the Pope, no less, asking him to write a book! Kramer bounced over to his desk with quill and ink and a bucketful of enthusiasm. He was determined to prove just how right he’d been all along.

If this was the first textbook in criminology, it’s fair to say we were off to a poor start. One critic says, ‘Its style is poor, its ideas are foolish, its intentions are villainous, and the advice given to the inquisitors […] betrays a diabolical perfidiousness’.[vi] For sure, it’s fragmentary, biased, and ill-sorted, not so much journalism as agitprop. We can imagine Kramer aching to prove that witches really and truly existed. By doing so, he, Kramer - hobbyist, enthusiast, witch-nerd - would make the world a better, safer place.

Nothing is more seductive to certain people than the vision of themselves as both right and good.

Simple stereotypes helped. Witches gathered secretly, night by shadowy night, far from Christian eyes. They worshipped Satan and ate babies. They had special marks on their bodies. They copulated with demons.

No, really. Demonic copulation: that was especially interesting, and not just for the obvious reason. Especially interesting for Kramer, at any rate. You will recognise his reasoning. If they were able to copulate, demons must possess physical bodies like yours or mine. Copulation, after all, is sometimes called coupling, and one half of couple has to be as real as the other. And demons were no doubt exactly as evil as they were real. It followed logically that their enemy, the Church, must be evil’s opposite. It also followed that Kramer, their fierce foe, was good. Right and good.

Does this reasoning seem suspect? Soon it was heresy to reason any other way.[vii]

Suspect reasoning, weird logic, was a hallmark of the witch-craze. Christians must not fail to believe in their Enemy. Demons must not be allowed not to exist. If there was no persuasive evidence that cunning, invisible demons existed, that only proved how cunning and invisible they really were. Since witches were known to be liars, it was naive to believe them when they claimed they were not. The best evidence that the witches’ top-secret sabbats really did happen was the fact that no one had ever seen them. It proved just how top-secret they were.

Almost everything went to prove Kramer’s point. Did some people protest that the holy Inquisition was too repressive? They were evidently in sympathy with Satan. Did the accused scream and plead for mercy? That was how witches cast their anaesthetic spells. Did they claim to know nothing about the crime of witchcraft? That was a crime as well. Did torture fail to extract a confession? Torture the witch again.

In modern Tanzania, some people believe that witches cause death on sight. For precisely that reason, there is no proof that they exist. This fact does nothing but make them seem even more powerful.[viii]

Double negatives

If it had been a party, all the witches would have turned up in the same dress. If it had been a confessional, their priest would have been bored to tears.

Satan had approached at a time when they felt particularly vulnerable. The present seemed unbearable, the future even worse. Perhaps they were angry, lonely, or hungry. Satan promised vengeance, comradeship, nourishment. In return, they must accept him as their master. He placed his mark upon them. He raped them. He took away all hope of salvation. And then the Father of Lies broke every promise he’d made.[ix]

He was a contradiction, this archfiend. Extraordinarily active, yes, but not always exactly frightening, not always particularly evil. He wasn’t, so to speak, convincing. His Satanic Majesty seemed to spend a lot of time pratting about. He had the talent, (anyone could see that,) but he didn’t apply himself. He lacked dedication, imagination, and wit. He’d pay for beer with coins that turned to slate in the morning, or disguise himself as a duck and frighten people by quacking a bit loudly. Sometimes, he’d trip up pedestrians with his tail. What a joker. Only occasionally did he buckle down and put in some effort. Only then did he send fire and flood.[x] Only then did he recruit witches.

What his victims took to be Satan was surely no more than theirown emotions, projected.[xi] Modern psychologists know about the sensed presence effect. The victim is in mortal peril. Their mind conjures up a guardian angel. Explorers, mountain climbers, and the like know all about this.

Imaginary or otherwise, Satan could not have appeared more real, either to his victims or their accusers. That was the source of his power. Satan was frightening because he was real; he was real because he was frightening.

Few people disagreed. To be an uneducated person was to live in fear of dark forces loose in the world: to be an educated one was to understand how they were supposed to operate. How did the witchcraft actually happen?[xii] Early Modern demonologists started trying to explain maleficium.

And there was plenty of it to explain. Tragedy takes endless shapes. Animals sometimes sicken, gales sometimes blow, babies sometimes die. Perhaps your chimney fell down; perhaps you forgot to put salt in your cheese; perhaps you caught yourself dancing naked in the yard one night. Perhaps your horse’s blood disappeared, or, worse, perhaps your penis did.[xiii] In panic, you might point a finger at the town’s least-loved old lady. And if she was nowhere to be seen, well, everyone knew that witches could turn invisible. All of this was maleficium. All of this was the work of witches. And all of this was unique to Early Modern Europe.

Only there was maleficium demon-dependent. In other parts of the world, at other times, maleficium was and is the work of the witch herself.[xiv] Demons are neither here nor there.

You can imagine why. Our Early Modern witchfinders were determined to see the magic and feel it. They needed a physical demon, one that left tracks. Why?: because they wanted to track it down.

‘Determined’ is the word. We saw earlier that, if faith was a ladder to Heaven, demons were a crucial rung. As long as you believed in them, you could continue to climb. A faithful witch-finder might yet avoid Hell.

The linguist Walter Stephens has a good name for the witch-finders’ attitude. He calls it ‘resistance to scepticism’. It is simple enough to say that the witch-finders wanted to believe. The truth, however, was more subtle. Witch-finders did not want not to believe. They were like stock-pickers shovelling cash into a market that kept on falling; gamblers betting on horses that fell further and further behind. Because they could not afford to continue, they could not afford to stop. Their bets grew bigger as the evidence evaporated. They doubled down on those double negatives; doubled down again. It was hopeless, but it was the only hope.

In the era of science, witchcraft was inevitably doomed. But some – some had to keep beating against the current. Some had to. More about that in a later newsletter.

All pictures courtesy of Wiki Commons.

References supplied partly out of academic habit; partly so that you can read more about anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Kadri, Sadakat: The Trial – A history from Socrates to OJ Simpson, Harper Perennial, London, 2006, p110-112

[ii] Carus, Paul, The History of the Devil & the Idea of Evil, Open Court, Illinois, 1974/1994, p286

[iii] Asma, Stephen T: On Monsters – An unnatural history of our worst fears, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2009, p107

[iv] Stockstad, Marilyn (in collaboration with Cateforis, David): Art History - Revised second edition, Pearson Prentice Hall, New Jersey, 2005, p661

[v] Hutton, Ronald, The Witch - A history of fear, from ancient times to the present, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2017, p170-2

[vi] Carus, Paul, op cit, p323

[vii] Clark, Stuart: Thinking with Demons – The idea of witchcraft in early modern Europe, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999

[viii] Scarre, Geoffrey, Witchcraft & Magic in 16th & 17th Century Europe, Macmillan Education, London, 1987, p13, p40

[ix] Scarre, Geoffrey, op cit, pp19–20

[x] Mackay, Charles, Extraordinary Popular Delusions & the Madness of Crowds, Wordsworth Reference, London, 1841/2006, pp388-9

[xi] Scarre, Geoffrey, op cit, p89

[xii] Roper, Lyndal, “Witchcraft and the Western imagination”, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 16 (2006), 141

[xiii] L’Estrange-Ewen C: Witchcraft & Demonianism, Frederick Muller Ltd, 1970 pp 331-383

[xiv] Hutton, Ronald, op cit, px