EYEWITNESSES: THE FIVE THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW

The paradox of eyewitnessing; purse-snatching; facial recognition; prosopagnosia; misinformation; traffic accidents; police interviews

A psychologist named Roger Brown once wrote about ‘the paradox of eyewitnessing’. Psychologists consider eyewitness testimony a byword for untrustworthiness. Jurors however tend to find it more convincing than just about any other kind of evidence. (I say ‘just about’ for the simple reason that today’s lawyers also mourn over the ‘CSI effect’. Jurors watch too much television and are therefore likely to wonder why the prosecution has failed to supply DNA swabs, colourful charts, and distinctive carpet fibres.) For sure, it makes compelling courtroom drama when the eyewitness points at the defendant and cries, ‘That’s the man, over there, I’ll remember his face till my dying day!’ Under such circumstances, the juror may consider the question of reasonable doubt to have been compendiously answered. This fact raises another question: ‘Why should laymen and psychologists be so far apart in their evaluation of eyewitness identification since, after all, everyone every day recognizes people or fails to do so, and it does not seem as though it should be necessary to do experiments to determine how accurate recognition is?’[i] The answer lies in a thought experiment. If you live in a city or medium-sized town, imagine walking around your neighbourhood for a few minutes. Treat the people you pass as an identity parade. How many faces have you seen before? Maybe a few – let’s say you estimate two out of a hundred. Are you correct? Well, unless these are people you know well enough to say hello to, there’s no way to tell. Maybe they were simply ‘false alarms’. And how about the remaining 98? Were you right to think you hadn’t seen them before? Again, there’s no way to tell. Perhaps you glimpsed them in a cinema queue last month, or shopping at Christmastime. One thing is sure: you’re not going to walk up to these strangers, peer closely at them, and check. In neither case – thinking you recognise a face or thinking you do not – do you get any feedback. That’s why we often reckon we’re better at it than we are.

Eyewitnesses typically see the whole suspect, not just their face. For that reason, they will naturally have some idea of their body build.[ii] This rarely comes up in the courtroom, though, or even in the psychology literature. What we focus on is memory for faces. How good are we at it? Really rather poor, it seems, at least when it comes to the faces of strangers. We are almost certainly much worse than the typical juror imagines. The literature on this topic is vast. It would take a book – a library shelf - to deal with it. But let’s find room for a study by Robert Buckhout. He made a film of a ‘representative’ purse-snatching (‘representative’, anyway, in 1970s Manhattan, where Buckhout found himself). The film was just thirteen seconds long, and I can tell you, having once done a similar experiment myself, that’s practically a cinematic epic: a New York purse-snatcher is there and gone in a New York minute. Buckhout included the film in a television news show, followed by a filmed line-up of six men standing against a wall. Each man had a number. Viewers were invited to phone the news station and identify the guilty party. If they guessed randomly, you’d expect the viewers to get it right about 16.7% of the time (that is, one time in six). Well, 2145 viewers called in and correctly identified the mugger 14.1% of the time. That means their performance was actually worse than chance.[iii] Right there is one reason why psychologists are a dubious.

Surely, though, we can be confident that human beings, under most circumstances, have a pretty solid track record when it comes to facial recognition? It certainly makes good evolutionary sense. Although we are hardly the biggest, strongest, or fastest creatures in the world, our species has proven extraordinarily successful. That’s partly because of our cooperative nature. Cooperation, of course, relies on our ability to recognise each other. One group of researchers found that, from a high school class of 150, members could still recognise each other with about 90% accuracy after 35 years.[iv] That’s an impressive ability. Even so, members of a high-school class are hardly equivalent to purse-snatchers. Their faces are familiar. Almost by definition, most criminals will have faces that are unfamiliar. It seems that we have two different sets of hardware for facial recognition: one for familiar faces and one for unfamiliar ones. The former is fast, unconscious, and has emotional content. The latter is slow, conscious, and does not. Consider a rare syndrome called prosopagnosia. Sufferers have experienced trauma to a pathway in the brain that seems to be specialised for recognising familiar faces. (I once met a man who could recognise his wife only by memorising her hairstyle. One day she came home with a new one and was understandably upset when her husband panicked at this intruder who’d walked into their house.) One startling syndrome is called the Capgrass Delusion. Sufferers have the frightening belief that a close friend or family member has been replaced by an identical-looking imposter. They see the face and know perfectly well that it’s familiar: maybe it belongs to a husband or wife. Along with that face, though, they’d expect to experience a certain quantity of emotion (positive ones, we hope). With all emotion absent, they find themselves in the disorienting position of looking at their spouse, say, and feeling…nothing. There’s only one explanation – this can only be an imposter with an identical face. Recognising a criminal may be a wholly different process from recognising friends, family, or work colleagues.

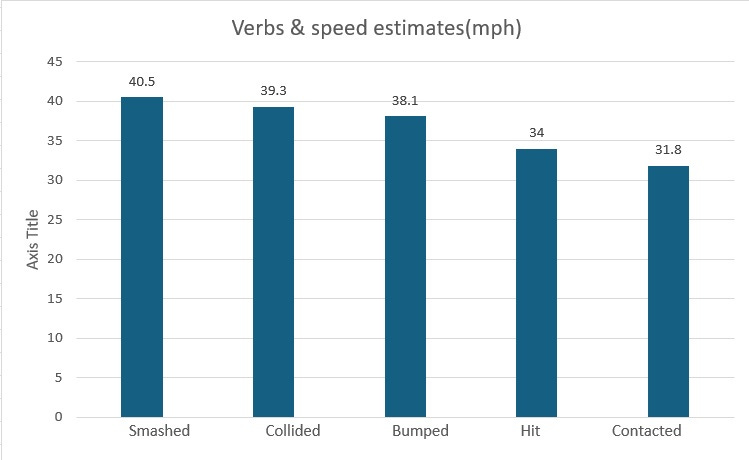

Have you heard of ‘false memories’? They were once something of a growth industry in psychology. We can trace their origins back to a paper from 1974. It may be the most influential in the eyewitness literature. Elizabeth Loftus has studied the ways in which our memories for events like car accidents or crimes can be altered by information learnt after the event was witnessed. In her long-ago experiment, participants watched a film showing a car crash. They completed a questionnaire that tested their memory of the event. One of the questions asked how fast the cars were going. That’s exactly the kind of question that a real eyewitness might be asked by, say, a claims investigator or police officer. Witnesses heard one of five different questions: ‘About how fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?’; ‘About how fast were the cars going when they collided?’, and so on. The other verbs were ‘hit’, ‘bumped’, and ‘contacted’. Different verbs produced different estimates. Check out the chart below:

As you can see, estimates were highest when the verb was ‘smashed’ and lowest when it was ‘contacted’. In a follow-up experiment, the researchers discovered that the form of the question genuinely altered participants’ memories. ‘Did you see any broken glass?’ they asked. Participants in the ‘smashed’ condition were far more likely to misremember this fictional glass.[v] This so-called ‘misinformation effect’ is easy enough to replicate and very difficult to remove. It has clear implications for police interview procedure, since the very words a police officer uses in a question seem to affect not only what the witness says but even what they think they remember.

Speaking of police interviews, you won’t be surprised to learn that researchers have tried to discover psychological techniques for generating true, useful information from eyewitnesses.[vi] One technique that has received a lot of publicity is the so-called Cognitive Interview. Traditional police interview techniques have consisted of simply asking a witness freely to recall the event in their own words, after which the investigating officer tends to ask a number of specific questions (often closed ones such as ‘Was the car blue or was it green?’). The Cognitive Interview seemed to offer a 30% improvement in the quantity of correct material remembered, without any matching increase in the quantity of incorrect information. When it was revised in the 1990s, the improved technique seemed to offer a remarkable 45% increase over the original, meaning almost a 100% increase compared to the standard police interview.[vii] That’s quite an achievement. The Cognitive Interview consisted of four strategies, known as mnemonics, for the witness to work through. The first was Mental Reinstatement of Context. The witness had to think back over the time and place of the crime, remember what the weather was like, how they were feeling, how they were dressed, and so on. Psychologists know that reinstating context in this fashion this can be very effective (and worth knowing next time you lose your keys). The second mnemonic was Reporting Everything. The witness was asked to tell everything they could remember about the incident, whether it seemed relevant or not. Even tiny details can help reinstate the context, of course, and they can sometime prove forensically useful. The third mnemonic was Changing Order. Naturally, witnesses usually start at the beginning and work their way to the end. Instead, they were encouraged to tell the story backwards, or even start in the middle. Last came the Change Perspective mnemonic – which meant telling what they would have been able to see, had they been standing elsewhere, or how they might have interpreted the event had they been, say, a child, or someone who worked in the area. All in all, the techniques led the witness to tell their story in different ways, each of which may add value. Reviews of the Cognitive Interview after decades of use indicate that it generally leads to lead to fuller, more detailed recall. That’s the good news. Less good is the fact that it may lead witnesses to confabulate or produce more incorrect details than a standard police interview.[viii] Police officers sometimes report they find it rather a clunky affair. It’s as time-consuming to administer as you might imagine. It also produces a lot of clutter in the way of unnecessary detail. Sceptical psychologists claim that the benefits of the Cognitive Interview come from nothing much more technical than the extra time and effort devoted to the witness, which naturally increases their motivation to help. Individual mnemonics alone may be little more effective than simply being asked to ‘try again’.[ix]

[i] Brown, Roger: Social Psychology - The second edition, The Free Press, New York, 1986, p261

[ii] MacLeod, Malcolm D; Frowley, Jason N & Shepherd, John: ‘Whole-body information – its relevance to eyewitnesses’, in Ross, David Frank; Read, J Don & Toglia, Michael P: Adult Eyewitness Testimony – Current trends & developments, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1994, pp125-142

[iii] Buckhout, R: ‘Nearly 2000 witnesses can be wrong’, Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 16, 1980, pp307-10

[iv][iv] Bahrick HP, Bahrick PO & Wittlinger RP: ’Fifty years of memory for names & faces – A cross-sectional approach’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104, no 1, 1975 pp54-75

[v] Loftus EF & Palmer JC: ‘Reconstruction of automobile destruction – an example of the interaction between language & memory’, Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 13(5), 1974, pp585-9,

[vi] Kebbell, Mark R & Graham F Wagstaff: ’The effectiveness of the cognitive interview’, Interviewing & Deception, Routledge, New York, 1999

[vii] Fisher RP & Geiselman RE: Memory-enhancing Techniques for Investigative Interviewing, CC Thomas, Springfield, 1992

[viii] Memon A, Meissner CA & Fraser J: ‘The cognitive interview – A meta-analytic review and study space analysis of the past 25 years’, Psychology, Public Policy & Law, 16(4),2010, pp340-72

[ix] Milne, Rebecca & Bull, Ray: ‘Back to basics – a componential analysis of the original cognitive interview mnemonics with three age groups’, Applied Cognitive Psychology, 16, 2002, pp743–753

The power ascribed to eyewitness testimony is worrying given how inaccurate it can be. There are likely many people who have been imprisoned on that kinds of testimony alone. Given our experience with magicians and illusions and how poorly we remember it is perplexing why eye witnessing continues to play such an important role.

This is so interesting and it reminds me of all my years in auto insurance. Even when someone is recalling something they were intimately involved in first hand (like an auto accident), they frequently mistakenly report all sorts of things. People don’t do it intentionally, it’s just how we’re wired. We’d get reports from people saying they saw a car coming at them and it was “three minutes” before impact. (It couldn’t be more than seconds), or they mentioned trees that blocked their view that didn’t exist, and on and on. It’s objectively fascinating, but also frustrating, because witness testimony is unreliable.