CRIME STORIES, TWO DIFFERENT ONES

Sensation fiction; whodunits; The Golden Age of detective fiction; clue-puzzles; pulps; hardboiled novels; films noir; superheroes; censorship

According to one classic account, you can easily tell when you’re reading a crime story, as opposed to the simpler forms of fiction. Crime stories don’t limit themselves to just one narrative. They insist on two. Story One is about the offence; Story Two is about the investigation.[i]

Here is another way of putting it: Story One is Crime; Story Two is Criminals. Different genres place the emphasis differently. The traditional detective story, for instance, emphasises Story Two, while the modern thriller emphasises Story One. (Particularly sophisticated examples, such as the HBO series True Detective, and certain Sherlock Holmes stories, may even weave in a Story Three, about the reinvestigation of the original investigation.)

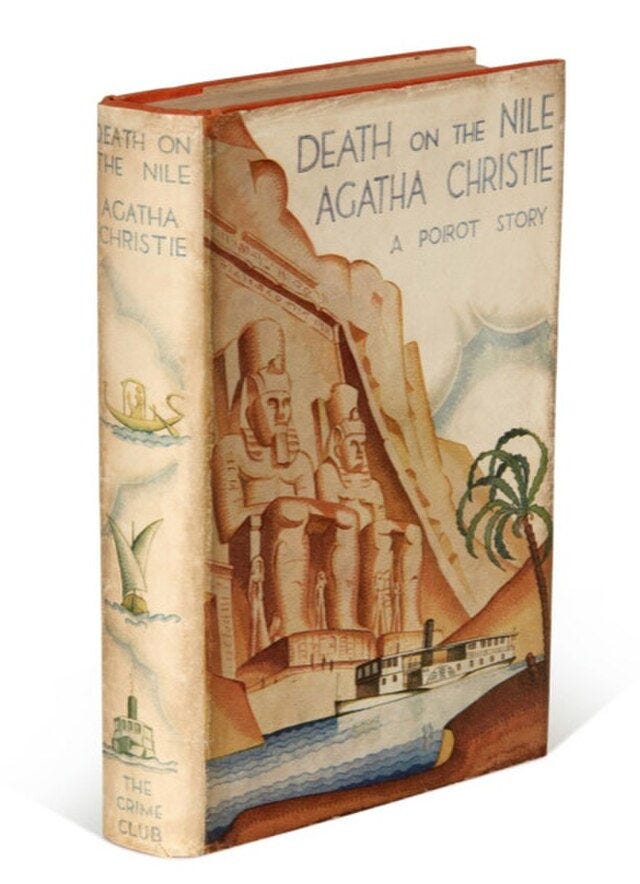

Two is the vital number. Over the course of the last century or so, crime fiction has enjoyed exactly that many ages.[ii] The twins were separated not just by a decade or more in time but also the entire Atlantic Ocean. Between the World Wars, but dating at least to 1913,[iii] readers swooned for the The Golden Age, the British era of Agatha Christie, Marjorie Allingham, Dorothy L Sayers. Think of gentle murders, locked-room mysteries, ‘polite mayhem amidst the tea-cosies’.[iv] Richard Osman continues the tradition, and don’t we wish he didn’t?

This is fiction as a comfort: even when other people’s lives ended abruptly, the British library-card holder could rely on cool intelligence and rationality to fix everything in the end, even if one did have to rely, sometimes, on foreigners to do it on one’s behalf. The Belgian Hercule Poirot, for instance, was forever employing those ‘little grey cells’ of his to reassemble England’s shaken jigsaw.

The Golden Age saw detectives doubling as philosophers, forever sifting clues from red herrings, suspects from bystanders. If he happened to have read a few Golden Age stories himself, our detective might start off with some advantages. He’d know, for instance, that servants are almost never guilty, because the real killer orbits in the same circles as the victim. Every suspect has a motive. The victim barely matters – he or she was never popular in the first place. Finally, the detective-philosopher could be sure that all the necessary clues were right there in front of him. Not a piece would be missing.[v] The so-called clue-puzzle, not coincidentally, was invented at almost exactly the same time as the crossword puzzle.

What about second age of the crime story? Frontier fiction had been popular in the dime novels of the nineteenth century: stories about sheriffs and gunslingers out in the Wild West. Around the century’s end, the first American detectives appeared. Although they were New Yorkers, they might as well have been transplanted gunslingers, shooting it out on the city’s own twin frontiers, Broadway and the Bowery. It took twenty years for the detective to migrate to California.[vi]

Pulp magazines like Black Mask appeared around the same time as Prohibition. With their colourful covers, flamboyant fiction, and tiny price-tags, they helped form the literary tastes of a generation. A generation of criminals – Prohibition saw to that.

No one cared for whodunits any more, not when everyone was doing it. Crime stories changed:

“[Dashiell] Hammett gave murder back to the kind of people who commit it for reasons, not just to provide a corpse; and with the means at hand, not hand-wrought duelling pistols, curare and tropical fish. He put these people down on paper as they were, and he made them talk and think in the language customarily used for these purposes”[vii].

Naturally, the quote is from Raymond Chandler. You can tell by the language. Language mattered to the hard-boiled school far more than ever it had to the Golden Age writers. Reviewers have a special way of describing their shared style. They use the words that are as accurate as they are inevitable: clipped; gritty; slangy; streetwise. The language is poetical even when the crimes are not - beatings, betrayals, blackmail.

At length, the novels began to tell events from the criminals’ point of view. They put you in his shoes, or balaclava, or getaway car. They asked whether You, the reader, were capable of the crimes you were reading about. The whole cast is damaged, every action is compromised. Everything is ambiguous. No fences separate Us from Them. No one can escape.

Indeed, where would you go? In Depression times, the cinema had been one option. From the dingiest fleapit to the gaudiest Alhambra, films offered a rare chance for escape. The biggest attractions were the A-list films with their A-list stars, but the studios refused to sell them on their own. They packed them together with B-list films. This system was called block-booking. In 1948, the US Supreme Court made it illegal. That decision put an end to a golden period of film-making. With B-list films in endless demand, there had been plenty of room to experiment. Émigré Europeans, let loose with brand-new equipment, invented a whole genre.

Film noir was altogether new. Tinseltown had previously dealt in comedies, melodramas, musicals, westerns: films made in the shape of fairy tales. Some rather-predictable gangster flicks had preached that crime never paid. You always knew what you were going to get. You always knew that the baddies were gonna get theirs. Noir shifted the gears into reverse. Flawed heroes turned out to be villains. Their angel-faced partners turned out to be even worse. Noir was about sure things that weren’t, love affairs that resembled obsessions, places that might be somewhere else.

You couldn’t even rely on the big stars. One feature of noir was to cast them against type, or as their own alter egos. Double Indemnity (1944) set the standard. Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray, both well-known for playing goodies, became a creepy couple who spent two hours planning, committing, and regretting a murder. Another hero became an anti-hero when Humphrey Bogart appeared in The Maltese Falcon (1941) as the murkily-moral Sam Spade.

Both films were based on books by hard-boiled writers: James M Cain and Dashiell Hammett (Chandler, the third member of the trinity, worked on the script for Double Indemnity). The genres shared style and themes.[viii] Both dealt with moral ambiguity; both dealt with Criminals as opposed to Crimes; both gave a mazy sense of being lost in the head of someone unable to learn life’s lessons. Both featured realistic, shifty characters with dirty collars, paranoid eyes, and West-Coast accents.

That West-Coast element was vital. Los Angeles virtually became a movie-star in its own right. The cinematographers gave it the same edgy lighting you see in seventeenth-century Dutch painting. The underlit city made the perfect stage-set for grimy sagas of ambition, corruption, and duplicity. Did you exit the cinema wanting to wash your hands? The director would be delighted to hear it.

But everything new grows old. By 1959, cinema needed something fresh. Alfred Hitchcock supplied it in the sleazy form of Psycho, whose villain was modelled on the fearsome Ed Gein, Wisconsin’s own farm-boy cannibal. The film is about madness, and the secrets that cause it. Every character is hiding something, whether it’s stolen money, their real identity, or a petrified corpse. Mirrors distort reality and images are constantly sliced and spliced to reflect the broken, bitty world of the murderous schizophrenic. Hitchcock designed it to make you, the viewer, feel complicit in crime. Perhaps it’s no coincidence that the film appeared in the same year as RD Laing’s bestselling book about mental pathology, which was called The Divided Self.[ix]

Noir’s heyday coincided with the first adventures of a new breed of crime-fighter. They wore capes and leapt tall buildings in a single bound. Superheroes lived up to their name in more ways than one. The traditional story of the hero begins with a person of great promise and ambition, who has their eye on some sort of prize: a kingship; a trophy; a million bucks. They suffer a terrible set-back – injury, defeat, bankruptcy – only to regroup, come back stronger than ever, and triumph. All countries have these myths. Being a new one, America had to invent its own from scratch. Superheroes were the latest and greatest invention.

America’s superheroes appeared at the same time as its home-grown social bandits. The masked crime-fighter Zorro had a stylishly-clad foot in both camps. After him came the Spider, Doc Savage, and, most notably, the Shadow, who ignited a craze for mysterious crime-fighters: Crimson Avengers, Green Hornets, Phantom Detectives.[x] All three were in action by 1933. The comic-book industry was finding its feet. It was the triumph of a shadowy cabal of bootleggers, racketeers, pornographers, and pulp-fiction publishers. The vital date is April, 1938. Superman’s very first adventure appeared in Action Comics #1.[xi] Will Eisner’s peerless creation, The Spirit, debuted the following year.

The Golden Age of comic-books lasted till the early fifties. The characters who appeared include Batman, Captain Marvel, and Wonder Woman. Even the Second World War could not slow them down. That took the headline-grabbing real-world adventures of Bonnie and Clyde, John Dillinger, and Pretty Boy Floyd. Publishers cashed in even as superheroes cashed out. They began producing crime comics. Indeed, the superheroes’ own creators, DC, even branded their company after their flagship title, Detective Comics.[xii] There were monsters, too. In 1947, William Gaines took over EC Comics. He launched titles like The Vault of Horror, War Against Crime, Tales from the Crypt. His stories were so adult and sophisticated that the serial killer Ted Bundy blamed them for his crimes.[xiii] How popular were they?: By 1952, the market had room for 696 comics titles.

Kids were actually reading! It was a miracle! Someone had to stop them! In 1954, a psychiatrist named Frederic Wertham took on the task that had stumped Lex Luthor: defeating Superman. In his book, The Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham claimed that comic-books caused juvenile delinquency. There was a national enquiry. There was a Comics Code Authority. The industry adopted a code of ethics and standards: “All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, masochism shall not be permitted”.[xiv] Damn.

Wertham seems to have been a duplicitous campaigner, not above manipulating data for his own purposes.[xv] Yet the effects of his dishonesty were devastating. Twenty-four publishers shut down. Who-knows-how-many writers and artists lost their income. Crime and horror titles vanished. Although superheroes staggered grimly on, they’d been hurt badly. Those who survived were those best adapted to America’s rip-roaring new Space Age, with its fresh-from-the-box mania for aliens, UFOs, and rockets.

That’s where a new, upstart publishing company came in. Its epic story began with a dysfunctional family, bombarded by gamma rays on an outing to space. It continued with the tale of a repressed scientist caught near a detonating bomb, and a misfit teenager bitten by a radioactive spider. The Fantastic Four, the Hulk, and Spider-Man embodied a whole new concept: only one personality was a hero. The other was as flawed as you or me. Most extreme was the Hulk. He was barely a hero at all, but comics’ answer to Jekyll and Hyde (mostly Hyde).[xvi] And then there were the X-Men. What were they but every teenager’s “feelings of alienation and self-consciousness given flesh, fur, and feathers”?[xvii]

DC’s flagship hero, Superman, “represents an ideal we can never achieve, and we know it; that’s pretty much the point of him”.[xviii] That’s why Superman is literally no one’s favourite superhero. But Marvel’s characters were really characters. They were like Us. Us, that is, if we could fly, spin webs, or turn green. They were the Us we wanted to be, the Us that We knew We really were, somewhere deep inside. They, meanwhile...well, They took the form of supervillains. Yet They were real characters too: They had Their motivations and Their humanity. It might still be Us and Them, but the lines were blurring.

With time, the blurring continued. Comic-books faced competition from television, movies, games. They had to push back. And push some more. Frank Miller’s satirical, über-violent graphic novel, The Dark Knight Returns, not only showed a new sort of Batman - a crazily-compulsive testosterone-torched psychopath - but also showed how much his fans liked him that way. Today’s most popular superheroes are barely distinguishable from the villains. They’re knuckle-dragging mouth-breathers with names like Deadpool, Deathstroke, Shrapnel. We have merged with Them. Fans have known for decades that Batman and the Joker come as a pair. They’re twins. If Batman is an orderly obsessive, the Joker represents chaos. Their relationship is encapsulated in another well-known character from Gotham, who tosses a coin at the scene of every crime. When the scarred face comes up, he acts like a villain. What are Batman and his Joker but the two faces of Two-Face’s coin?

And yet the fact that I can write all of this proves that attacks from the superhero’s nemesis did at last prove futile. The superhero triumphed. He assumed his rightful place in Western mythology. What human face on the planet is more widely recognised than Spider-Man’s mask, or Iron Man’s? The superhero became a king, got his trophy, won that million bucks. At least one scholar sees all this as a “celebration of individualism that [...] often acts as a mask for conservative political values”.[xix] Maybe so. More on that another time.

If you enjoy Crime & Psychology, I encourage you to show your support by clicking a blue button, or even buying me a coffee. Awww, go on. You can do it here. Thank you!

[i] Todorov, Tzvetan: “The typology of detective fiction”, in The Poetics of Prose, Blackwell, Oxford,1977

[ii] Bradford, Richard: Crime Fiction – A very short introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxon, 2015, p19

[iii] Knight, Stephen: “The golden age”, in Martin Priestman (ed), The Cambridge Companion to Crime Fiction, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009, p77

[iv] Forshaw, Barry: The Rough Guide to Crime Fiction, Penguin, London, 2007, p171

[v] Knight, Stephen, op cit, p77; pp78-9

[vi] Porter, Dennis: “The private eye”, in Martin Priestman (ed), op cit, p98; 95

[vii] Raymond Chandler, quoted in Porter, Dennis, op cit, p96

[viii] Moody, Nikkianne: “Crime in film and on TV”, in Martin Priestman (ed), op cit, p233

[ix] Watson, Peter, op cit, pp490-91

[x] Weldon, Glen: The Caped Crusade – Batman & the rise of nerd culture, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2016, p17

[xi] Robb, Brian J: Superheroes – From Superman to The Avengers, the evolution of comic book legends, Robinson, London, 2014, pp22-23; p26

[xii] Cowsill, Alan; Irvine, Alex; Manning, Matthew K; McAvennie, Michael & Wallace, Daniel: DC Comics Year by Year – A visual chronicle, Dorling Kindersley, London, 2010, p17

[xiii] Forshaw, Barry, op cit, p35

[xiv] The Comics Code, quoted in Cowsill, Alan Irvine, Alex; Manning, Matthew K; McAvennie, Michael & Wallace, Daniel, op cit, p74

[xv] Weldon, Glen, op cit, p45; pp48-9

[xvi] Robb, Brian J, op cit, p132

[xvii] Weldon, Glen, op cit, p110

[xviii] Weldon, Glen, op cit, p3

[xix] Beaty, Bart: Frederic Wertham & the Critique of Mass Culture, University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, 2005, p201

Fascinating post, to some degree, I wonder what else is going on in the world in parallel -- does the decline in rationality in these pieces of fiction follow some kind of failing of those systems... in other parts of life/culture/politics...is the blurring of hero/villain happening during the later cold war where many recognized that the US's foreing policy often involved playing the villain or at least using thier tactics? Are these trends revealing something deeper about other socio political changes?