CRIME AND HEURISTICS Part 1

Victims; cognition; jury decision-making; eyewitnesses; learning; heuristics

A man has lost an arm because of a gunshot wound. He was shot when he walked in on a robbery taking place at a local convenience store.

In fact, there were two, similar, stores in the man’s neighbourhood. Have a think about these possible scenarios:

(i) The man usually shopped at Store A, but, on this one uncharacteristic occasion, Store A happened to be closed. He was shot in Store B, which he rarely frequented.

(ii) The man was shot at Store A, which was where he usually shopped.

Imagine it is your job to award the man compensation for the loss of his arm. Would you offer him more in scenario (i) or scenario (ii), or would it make no difference?

Almost certainly, your view is that it should make no difference (most people do). It’s immaterial where the shooting happened. What matters is that it did happen, and that it cost the poor fellow his arm.

In an academic Psychology experiment (technically using a ‘between-participants design’), people were presented with just one of the two scenarios, not both, as you were above. The researchers discovered that the victim was offered more compensation in scenario (i) than in scenario (ii). That outcome makes little sense if we really believe - as we seem to - that the location ought to be immaterial.

The explanation for this surprising discovery is a surprise in itself. It leads us into the fascinating world of heuristics and how they affect our thinking about crime.

When you look at the two scenarios side by side, as you did just now, you are also able consciously to examine your beliefs about justice, compensation, and so on. You can use your reason – and reason indicates that the location of the shooting should not affect the compensation. If, however, you were to see just one of the two scenarios, you would no longer be able to do that. Emotion starts to play a role. And one emotion seems to be vital: poignancy. You are able to think something along these lines: ‘Oh, no, if only Store A hadn’t happened to be closed, the tragedy would never have occurred’. This automatic emotional reaction quickly translates itself into financial terms[i].

A psychologist might put it this way: When you are confronted with the two scenarios, side by side, you invoke System 2 processing. When, however, you see just one, that’s when you rely on System 1 processing.

At this point, you may be shaking you head and saying, ‘Huh? System what now?’ Sit back and relax. I’ll show you what all of that means.

In an earlier newsletter, I explained how modern Cognitive Psychologists like to see the mind as an information-processing device, much like a laptop or mobile phone. (You can see the newsletter called WHAT WE THINK ABOUT WHEN WE THINK ABOUT CRIME here.) If you adopt this point of view, interesting consequences follow.

One is this: Your brain, like your phone or laptop, has only so much energy to spare – technically, we say it is a ‘limited capacity processor’. Yes, as your school Science teacher told you, it is the most powerful information-processor in the known universe, but even so it does have its limits. You simply can’t pay attention to everything that’s going on around you all the time. For that reason, we have evolved to use the limited capacity we have in the most efficient way possible. We prefer to use fast, efficient thinking strategies rather than clumsier, clunkier ones that may be more accurate but are also slower and more effortful.

In the context of Crime & Psychology, one example of a slow, effortful task springs immediately to mind. Jurors in court are tasked with something very effortful indeed. Their job is to attend carefully to lots of complicated evidence (days, weeks, even months of it), assess it all, weigh it all, consider how it fits with the complicated instructions they have received from the judge, and, taking all of that into account, produce a verdict that will have profound effects on the life of a fellow human being. That may be a perfect example of what psychologists call ‘cognitive overload’.

At the same time as they are doing all that, jurors have innumerable other variables to process. They must cope with the overwhelming, unfamiliar environment of the courtroom, the personalities of the strangers with whom they find themselves working, plus the technicalities of such apparent trivia as getting to and from court every day, rearranging their lives to suit the requirements of the trial, fitting in family and work obligations, and so on. It would hardly be a surprise if jurors, under such conditions, resign themselves to using fast, efficient strategies for making their decisions, rather than ones that are slower, more cumbersome, but ultimately more reliable.

In the past, psychologists thought that jurors approached their task in a scientific manner, weighing up the evidence, building and testing theories and hypotheses, creating statistical models of likelihood. This barely seems possible. Today’s psychologists believe that jurors are much more likely to use heuristics than algorithms. Jurors probably build and test-drive stories about what happened. One story comes from the prosecution; the other from the defence. Jurors get to decide which story seems more likely. Naturally, in doing so, they don’t rely on evidence alone. They incorporate their own life experiences, their learning, the question of whether similar things have ever happened to them, and even their general knowledge about how stories work (they generally have a definite beginning, middle, and an end, for example)[ii]. Stories tend to work in chronological order, too. We know that jurors are more tempted to believe the barrister who tells his or her story that way[iii].

As my old university friend, Daniel Hutto, pointed out, stories about people are not just narratives: rather, they have a job to do, which is to explain things. It’s virtually impossible to come up with something that is recognisably a story but which does not explain anything[iv]. ‘Why did Jason leave the party so early and in such a huff? There must be a story there…’

An heuristic called the overconfidence effect has a role to play here. Our confidence in our own judgements doesn’t rely as heavily as we might like to think on the quality or quantity of the evidence in front of us. What seems to matter much more is whether it flow together to create a coherent, believable story. (What makes a believable story to one person may not do so to another, of course. It all depends on our pre-existing beliefs and biographies, as anyone knows who has tried to convince a stranger in a bar of something they just didn’t want to know.) We very often fail even to notice when vital pieces of evidence – ones that would make all the difference to our judgement – are missing[v]. The psychologist Daniel Kahneman had a name for this phenomenon: WYSIATI. It stands for What You See Is All There Is. It’s why you can’t find your car keys when there’s a piece of paper lying on top of them.

Indeed, we’ve doubtless all heard stories of jurors who made their decisions for reasons we find a bit risible, if not outright ludicrous: ‘I didn’t like that attorney. He annoyed me’, or even ‘That guy was wearing a yellow tie! Who wears a yellow tie to court? I’m voting to convict!’ Jurors have been known simply to go along with other jurors, too, not because they thought they were right, but just to ease to process a little. Perhaps worse, they’ve been known to disagree with them just because they didn’t like them. There isn’t a great deal of that slow, effortful processing going on in a case like that. Reflections like these rightly worry anyone whose trial-date may be approaching.

Imagine an eyewitness to a short, brutal crime that occurs unexpectedly, under conditions of less-than-perfect visibility: say, an assault that happens at twilight, suddenly, on the other side of the road, in the evening, just as the sun is setting but before the streetlights have come on. Our eyewitness has a terribly difficult job to do. Everything counts against them. They were not prepared, for one thing, and may immediately have thought more of their own safety than trying to memorise details of height, weight, or clothing. Shock hardly helps the memory, either. A crime like this is likely to last only a matter of a few seconds, so the witness will probably have little time to move to a better vantage point, gather their thoughts, calm down, or anything like that. By the time such an eyewitness appears in court, they will have spent far, far more time being interviewed by police about the assault than ever they spent witnessing it. Again, everything militates against them, however strong their honest wish to do their task correctly. Our eyewitness is very likely to rely on fast, easy processing, rather than the difficult, effortful kind that may actually be required.

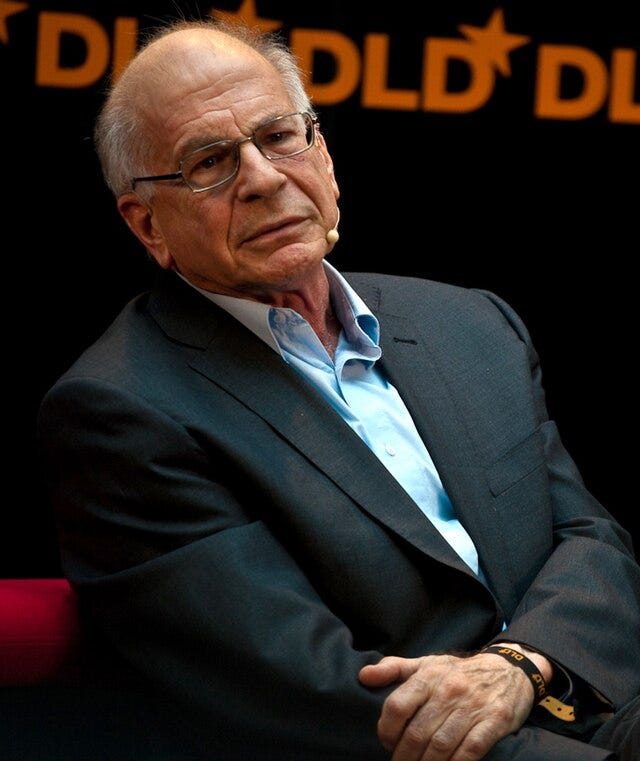

Fast, easy, processing is usually known as System 1. The slower, more logical, more difficult kind is known as System 2. This terminology comes from the work of Daniel Kahneman (who I mentioned above) and Amos Tversky. You may well have heard of Kahneman. He is the author of the well-known Psychology book, Thinking, Fast & Slow, which you can buy from all good bookshops, and even a few otherwise mediocre ones. (His book is where I got that example of victim compensation from – the one that opened this newsletter. I have provided the original reference for you below, just in case you’d like to chase it up.) Perhaps the most celebrated psychologist in the world, Kahneman won a Nobel Prize in 2002. This may have come as a surprise, for the simple reason that there is no Nobel Prize in Psychology. Thinking he deserved one, the Committee awarded him the Economics one instead. Amos Tversky sadly died in 1996, or else the two men would surely have shared their prize.

System 1 relies on heuristics - which are shortcuts in thinking that give us, usually, more or less the right answer to a problem, but without too much effort. System 2, meanwhile, relies on algorithms, which will always give us the right answer – but which, as we have seen, are slow, effortful, and feel like work. Limited-capacity processors to the last, we human beings prefer heuristics. In fact, we prefer them so much that we sometimes even fool ourselves into thinking we are using algorithms when really we are using heuristics. It’s less effort to fool ourselves than to keep coming up with correct answers to difficult problems.

You may be wondering how Kahneman and Tversky became involved in this area. If so, you’ll be delighted to discover that I’m about to tell you! The explanation will link us directly to another phenomenon in the criminal justice system.

Some time in the mid 1960s, Kahneman was giving a lecture at Hebrew University. Nothing unusual there, but what was more unusual was the fact that, instead of the usual line-up of undergraduates, his audience consisted of Israeli air-force flight instructors. Their job, as you can imagine, was to treat young pilots the subtleties of flying fighter jets. Kahneman told them a truth that we know from innumerable behaviourist experiments in the history of Psychology: reward (or ‘positive reinforcement’) aids learning. Punishment, not so much

Kahneman knew that this was true, but he also agreed with the instructors in his class when they told him their experience was otherwise. They found that when they shouted at their trainees for manoeuvres they performed badly, the trainees improved. When they praised them for manoeuvres they had performed well, the trainees tended to perform worse. Kahneman’s task was to work out how both could be true.

Eventually, he figured it out. (This is why Kahneman had a Nobel Prize: he was very smart.) What was happening was this: the trainees were learning some very complicated procedures, such as landing a plane. As you will know yourself, when you are learning something difficult, any variation from one trial to the next is essentially a matter of luck. While you may be getting better all the time, the effect of chance makes your improvement all but impossible to spot. Hence, a particularly bad landing today is likely to be followed – just by chance – by a slightly better landing tomorrow. A good landing today is likely to be followed – just by chance – by a slightly worse one tomorrow[vi].

Now, imagine your instructor yells at you every time you do badly. Just by chance, you are likely to be better next time. It will appear as if the yelling helped, even though it did not. Imagine your instructor praises you warmly and kindly every time you do well. It will appear as if the praise made you get worse.

Of course, the real effect is likely to be the exact opposite, but that’s not how it appears to you, the flight instructor, or even most professional psychologists until Daniel Kahneman came along.

The phenomenon is called regression to the mean. It’s the first of the half-dozen or so cognitive illusions we’ll deal with in next week’s newsletter. That fancy phrase, ‘regression to the mean’ simply means this: when things are bad, they get better. When they are good, they get worse. In other words, variables tend to return to their average. A really hot day is usually followed by a slightly cooler one, and the reverse for a really cold day. (This, incidentally, explains why patients who suffer from rheumatism tend to feel better after putting on a copper bracelet. The bracelet does nothing for the rheumatism, but they almost certainly put it on one day when the rheumatism was at its very worst. And when it’s at its very worst, by definition, there’s only one way it can go.)

That’s all for this week, faithful Crime & Psychology readers! I’m sure you’ve enjoyed this newsletter on cognitive heuristics nearly as much as I’ve enjoyed writing it. Never fear – we shall be back with more next time, when we’ll see how certain identifiable heuristics can illuminate our own thinking about crime. We’ll be dealing with terrorism, assassinations, snipers, and cowboy hats. All the cool kids will be there. So you don’t want to feel left out!

Don’t forget to blip the big blue buttons below.

Images of Daniel Kahneman and gun courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided largely out of academic habit, but also so you can chase up anything you find particularly interesting.

[i] Miller, Dale T & MacFarland, Cathy: ‘Counterfactual thinking & victim compensation – a test of Norm Theory’, Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 12, 1986, pp513-9

[ii] Pennington N & Hastie, R: ‘A cognitive theory of jury decision-making: The Story model’, Cardozo Law Review, 13, 1991, pp 5001-39

[iii] Asai N & Karasawa M: ‘Effects of the ease in story construction on judicial decisions concerning a criminal case’, Japanese Journal of Social Psychology, 28(3), 2013, pp137-46

[iv] Hutto D D: ‘The narrative practice hypothesis: origins & applications of folk psychology’ Philosophy, 60, 2007, pp 43-68

[v] Kahneman, Daniel: Thinking, Fast & Slow, Allen Lane, London, 2011, p87

[vi] Kahneman, Daniel, op cit, pp174-8

great column! Much of this points to severe deficiencies with the ways in which modern society's administer justice. I suppose if one were to design such systems nowadays they would likely look very different.