COMPOSITE CRIMINALS

Eugenics; portrait photography; mug-shots; slums; criminal environments; pornography; convicts; Bertillonage; what attractive faces look like

In recent years, it has become fashionable to dismiss Sir Francis Galton’s work out of hand. Authors routinely refer to “the eugenicist Galton”, and hurry on hastily to other topics, as if a label were sufficient to discredit the genius altogether. This is terribly unfair.

Galton did indeed invent the word “eugenics”. He even tried to promote selective breeding. He suspected that Africans were inferior to Europeans and women to men. None of that would win him any prizes today, let alone a knighthood.

We should remember that Galton did not share our benefit of hindsight. He could not know what the twentieth century would do with his ideas, or how he himself might be blamed. By all accounts, Galton was a gentle man who wanted only to improve human life. He would have been horrified to learn some of the history that you and I take for granted.

Galton’s contribution to science can hardly be over-stated. His career is all the more remarkable if we remember that he pursued it solely for the love of learning. Galton was one of those eccentrics who do not need to work for a living but do so anyway. He was interested in practically everything. He invented statistical techniques while sitting at the railway station, brewed the perfect cup of tea, made pioneering efforts in ballooning, and identified the anticyclone. He explored southern Africa, where he was so impressed by the women’s beauty that he couldn’t keep his hands off his measuring instruments. Let other men bring flowers: Galton preferred the sextant. He was among the first researchers in Anthropometry. This obscure word means “the measurement of people”. In the early days of Psychology, Anthropometry was vital. It quickly led to pioneering research on fingerprints.[i] The grooves that identify them are still called “Galton Marks”.

And then there was “composite portraiture”. Galton condensed a single image out of portraits of various people drawn from particular social groups. He started by tracing images onto transparent paper and holding them to the light. Later, he employed the camera, or, rather, the darkroom. Onto a single plate, he exposed eight portraits for eight seconds each.[ii] Later still, he employed an invention called the “double-image prism” (it was made by Mr Tisley, of 172 Brompton Road). The prism produced an image that was meant to be the average of a set of portraits - but an average you could actually look at. The centres tended to be clear, the edges blurry. The amount of blur indicated the spread around the prototype. It made a “generic picture of man, such as Quételet [whom we looked at in last week's newsletter] obtained in outline by the ordinary numerical methods”.[iii] It was statistics, but better.

We need a paragraph about portrait photography. It had two distinct functions. The first was more like science than art. Photographers made straightforward, objective images of the face. They were like mug-shots. Subjects were generally insane patients, the poor, and criminals.

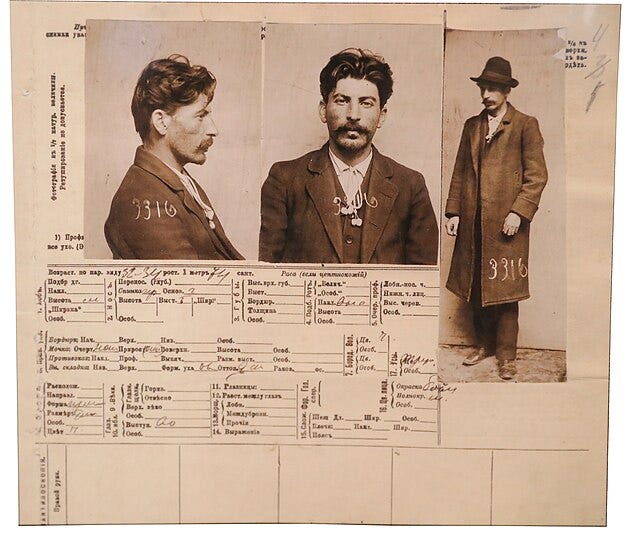

Any excuse is a good excuse for including Joseph Stalin’s mugshot.

The second function was almost the opposite. It was more like art than science. The photographs were meant to celebrate one’s respectable status. As you can imagine, the two groups of subjects rarely met and certainly didn’t socialise. It has been said that portrait photography helped define the “terrain of the other”[iv] – in other words, it helped separate the respectable and criminal classes. Photographs made clear the differences between Us and Them. The camera never lies!

European collectors sometimes kept photographic albums on their coffee tables. They could study natives of the countries that their own continent had recently colonised. The natives posed “with scientific detachment as specimens, as ‘the other’ to the European viewer”.[v] Their photographs rendered them not only alien, but inferior and subordinate. Some insist that modern photographs of prisoners do the same thing. No one looks handsome in a mugshot; no one looks good. Some prisoners believe that prison guards deliberately distort their portraits to make them into monsters. Certainly, the photographs tend to be taken when the prisoners are at their weakest and worst. This is not just an academic matter. An unworthy photograph indicates an unworthy prisoner, so it can affect a parole board’s decisions.[vi]

Jacob Riis (1849-1914) was a Danish emigrant to New York City, where he worked as a police reporter for the Tribune. Daring Riis took his camera into the rookeries and published a study called How the Other Half Lives. He hoped his bald, unsparing illustrations would help establish what the causes of crime really were. “By far the largest part [...] of crimes against property and against the person,” he wrote, “are perpetrated by individuals who have either lost connection with home life, or never had any, or whose homes had ceased to be sufficiently separate, decent, and desirable...” His subjects were New York’s shadow community, the negative numbers that cancelled out the rich, the comfortable, and the law-abiding. Retribution surely awaited if the landlords and other daylight-dwellers did not rectify the evil they had done. You could tell from the outside which tenements were most criminogenic. They “had the mark of Cain” about them. Some were so ugly even fire could not destroy them: such filthy walls would not burn.[vii]

Riis’s photograph of a crowded Mulberry Street tenement.

Riis’s photograph of Bandits’ Roost.

Meanwhile, new technology was being used for exactly the same purpose new technology has always been used for. Gutted shops were filled with “mutoscopes”. Horny customers spent spare change on short shows called “How shocking!”, “Naughty! Naughty! Naughty!”, or “Don’t Miss This!”[viii]

Galton collected “generic pictures” of convicts. He expected to find a distinctive look. He made composite portraits of killers and robbers.[ix] He got many of the originals from Edmund Du Cane, Director-General of Prisons. In 1871, the Prevention of Crimes Act had introduced photography into Britain’s criminal justice system. In the first year alone, police made 30,463 criminal portraits. The number was so overwhelming that, within five years, they restricted themselves to habitual criminals and parolees.[x]

A surprise lurked in these pictures. Galton noticed how different they were from each other – even when they featured the same person. It was worrying. Comments like this in The Times hardly helped: “The police authorities [...] have in their possession a series of 60 photographs of one and the same German girl...so different are the dress, the look, the expression and the whole appearance of the subject of these photographs...that the most clever detective might readily be imposed upon and fail to recognize the identity of the ‘artiste’.”[xi]

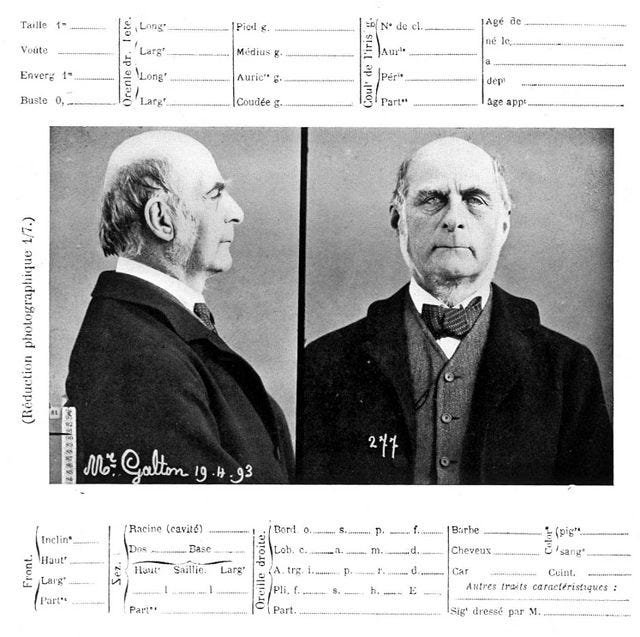

Galton’s composites proved sadly unpopular. A prison warder, after all, has little use for a blurry picture of a generalised burglar. He’d prefer a pin-sharp image of a particular one. That was exactly the sort of thing Galton’s French contemporary, Alphonse Bertillon, was developing. Bertillon had started measuring and photographing criminals on their arrest. He took ten measurements of each, from the length of the left foot to the width of the head. He took note of any stigmata, such as moles, tattoos, or scars. The probability of all eleven statistics recurring in two people were more than four million to one.[xii] The idea was to establish whether a particular individual had been arrested pre

viously. It was snapped up by police-forces around the world. They were so delighted, they named it after its inventor: bertillonage. It looked for a time as though bertillonage might become a permanent part of the crime-fighter’s toolkit. Fingerprinting put an abrupt stop to it. Poor Bertillon never recovered.[xiii]

You can see Galton’s own Bertillon record in the picture above.

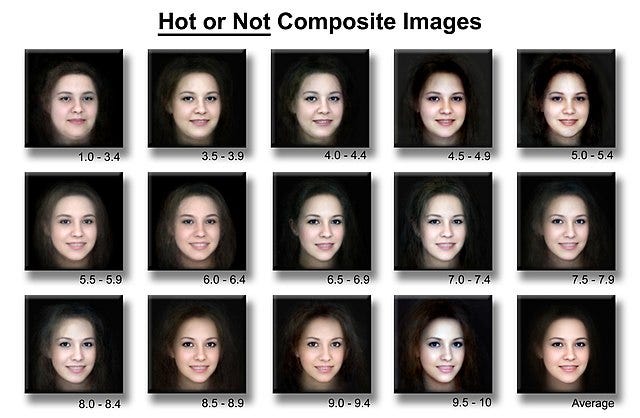

Failure though it was, composite portraiture produced one surprising discovery. “[T]he features of the composites are much better looking than those of the components. The special villainous irregularities have disappeared, and the common humanity that underlies them has prevailed”.[xiv] Villains’ faces became smoother, more symmetrical…more average.

I hope no one will accuse me of sexism here, but I could only find images of female composites. Take a quick squiz at the ones below. Lower rows incorporate more faces and are reliably judged more attractive:

A researcher from New Zealand discovered the same thing – although instead of criminals, he used society ladies. He found “in every instance, a decided improvement in beauty”.[xv] Modern psychologists, too, using techniques Galton could never have dreamt of, find that average faces are usually rather good-looking.[xvi] That may be good news for people with average faces, but it was less so for Galton. It seemed to disprove his hypothesis that there was an identifiable criminal “type”. What did that tell us about the “criminal class”?

More on that in an upcoming edition of your favourite Substack newsletter...Crime & Psychology! I’ve got some wonderful stuff waiting for you this summer, All you need to do, to support the newsletter, is play whackamole with the buttons below:

Or think about maybe buying me a coffee! That’d be nice.

[i] Thorwald, Jürgen: The Marks of Cain, Thames & Hudson, London, 1965, pp51-56

[ii] Galton, Sir Francis: “Composite portraits made by combining those of many different persons into a single resultant figure”, The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol 8 (1879) pp132-3

[iii] Sir Francis Galton, quoted in Stephens, Elizabeth, “Frances Galton’s Composite Portraits: The productive failure of a scientific experiment” Available at www.academia.edu/6746153/_Francis_Galton_s_Composite_Portraits_the_Productive_Failure_of_a-Scientific_Experiment Accessed 10th July, 2017

[iv] Sekula, Allan: “The Traffic of Photographs”, Art Journal (1981) No1 pp15-21

[v] Pultz, John: Photography & the Body, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1995, p23

[vi] Miranda, Diana & Machado, Helena: “Photographing prisoners – The unworthy, unpleasant & unchanging criminal body”, Criminology & Criminal Justice, 1-4, 2018

[vii] Riis, Jacob A: How the Other Half Lives – Studies among the tenements of New York, Benediction Classics, Oxford, 1890/2006, p3; p7;

[viii] Thomas, Donald: The Victorian Underworld, John Murray, London, 1999, op cit, pp170-1

[ix] Galton, Sir Francis, op cit, pp134-5

[x] Flanders, Judith, The Invention of Murder – How the Victorians revelled in death and detection and created modern crime, Harper Press, London, 2011, p349

[xi] The Times, quoted in Flanders, Judith, op cit, p387

[xii] Parry, Eugenia, Crime Album Stories – Paris 1886-1902, Scalo, Zurich, 2000,, p20

[xiii] Thorwald, Jürgen, op cit, pp116-127

[xiv] Galton, Sir Francis, op cit, p136

[xv] AL Austin, quoted in Sir Francis Galton, op cit, p137 (italics in original)

[xvi] Langlois, Judith H & Roggman, Lori A: “Attractive Faces Are Only Average”, Psychological Science, Vol 1(2), 1990, pp115-121

Another wonderful article! Lots to ponder here. First, like you say Galton was not good by our standards yet at the time he was gentle, appears to have been well intentioned and genuinely wanted to help society. We have made similar cases regarding Cartwright (claimed the desire for freedom was a disease) and Freeman (enthusiastic about lobotomy).

Fingerprinting is a really interesting story too. I recall there is an Argentine criminologist that developed a lot of the techniques to match fingerprinting to people because he thought it would help identify reoffenders. He also thought that fingerprints could be used to predict which people were more likely to commit crimes (more on this later).

The relationships between science, medicine, technology, and culture are really interesting and reveal much about society.

Fascinating! Looking forward to the next instalment on this. Despite no scientific evidence pointing to a recognisable criminal typeface, I'm sure we can pull 50 people who'll swear by their definition of a criminal typeface, haha.