COMMON SENSE DANCING

Why philosophers aren't laughing enough; jokes; kidnap; academia; terrorism; serial crime; coulrophobia; bureaucracy; the uses of mockery

First up: there is some near-to-the-knuckle material in this newsletter, including some by or about serial killers. Please don’t read it if you’re easily upset.

Still here? Glad to have you! Let’s talk about philosophers.

Philosophers ‘are too rarely amused’. So wrote Hugh Mellor, who we can doubtless trust on this subject, since he was a philosopher himself.

Lack of amusement is not a problem confined exclusively to philosophers. It is the experience of every brave soul who values the truth and seeks it out. Do you count yourself among that company? Bravery may not be the whole story. You may feel lonely, too. Truth has become a negotiable quantity in our postmodern world.

Lonely; brave; too rarely amused. ‘[P]hilosophy,’ writes Mellor, ‘has to deal amongst other things with the limits of what makes sense; that is, with the boundary between sense and nonsense, which is the very stuff of humour’.[i] The truth-seeker’s kit contains no more vital tool than the ability to sniff out nonsense. Or - perhaps better - to sniff out absurdity. If we do not know what absurdity consists of, how are we to recognise it in ourselves or others?

You know who had no sense of humour? You know who would not have recognised common sense if it hit him in the face with a custard pie? Robespierre, that’s who, that self-righteous prig who chopped the heads off half of France during the Revolution. Know who else? Fanatics and idealogues of all stripes. It’s not too easy to imagine Mao, Pol Pot, or Osama bin Laden at a comedy festival, is it?

Historians tell us that there used always to be laughter at important Nazi-party meetings. They tell us how Stalin enjoyed a joke. Not the best jokes, though. Never the best jokes. Here is Stalin:

‘Pauker […] played for Stalin the part of Zinoviev being dragged to execution. He hung by their arms, moaning and mouthing, then fell on his knees and, holding one of the warders by the boots, cried out “Please, for God’s sake, Comrade, call up Yosif Vissarianovich [i.e., Stalin]” Stalin roared with laughter, and Pauker gave a repeat performance. By this time Stalin was almost helpless with laughter…’[ii]

To continue the theme, The New York Times tells us that bin Laden laughed when he discovered that his hijackers ‘did not know they had volunteered for a suicide mission’.[iii]

Want to sniff out a few more people who lack a sense of absurdity? Simply check your Twitter feed.

One British university recently issued its staff and students guidelines about humour. ‘All jokes must be kind’, they said (and no, I’m not making this up). Kind. For three weeks I’ve been trying to work out what a kind joke might consist of. What would a ‘kind joke’ even sound like? How could it be funny? I am no closer to an answer than when I began. A joke, to be successful, must contain a shock, a surprise, a trapdoor. Very often, a joke is a sudden revelation of the reality behind the appearance. In intention, perhaps, a joke can be kind… but the execution? Well, it is called an execution.

Here is one of the world’s most successful comedians, a man you can bet knows what he’s talking about: ‘[I]t’s this edge of danger, this shadow side, that gives jokes their power. A joke is anarchic, a little scrap of chaos from beyond the boundaries of the rational, a toe dipped in the shallow end of anti-social behaviour’.[iv]

‘A joke,’ writes Jimmy Carr, ‘is seldom, if ever, a victimless crime. Someone or something is always the butt of it. And if we condemn all jokes which make fun of anyone other than the teller we are left with…cracker puns and knock-knock jokes’[v]. Is that what the campus authorities want? Cracker puns and knock-knock jokes?

Humour reveals our human need to feel included at the same time as it reveals our desire to flirt, just a little bit, with lawlessness.

You can bet cash money those guidelines were issued by one of those people. You know the ones I mean. The ones who grin suddenly and unconvincingly at parties when they notice that everyone else is laughing and don’t want to look like they missed something[vi]. The ones who dream about regulating this incomprehensible thing out of existence.

Let’s say that you or I make an argument that brings us to some nutty conclusion – one that’s self-evidently wonky. We know, immediately and without further reflection, that our argument must be faulty. Wonkiness alone is sufficient to prove that either the argument’s premises or its logic must be wrong. It must. Lacking the ability to recognise absurdity, many readers of Ayn Rand or Mein Kampf have found themselves doomed to accept wonky conclusions, or even wicked ones. Humour can actually be a defence against wickedness.

‘Knock knock!’ ‘Who’s there?’ ‘The police!’

To stamp out humour is a far worse crime than you think. The philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, wrote this: ‘...if it is correct to say that humour was stamped out in Nazi Germany, that does not mean that the people were not in good spirits, or anything of that sort, but something deeper and more important’. What it really means is this: a whole way of looking at the world was stamped out; a whole nation’s eyes were blinded. You can read more about the cruelty of such an act here.

Many people believe that another philosopher, Voltaire, said this: ‘Those who can make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities’. Voltaire, in actual point of fact, said no such thing (for one thing, he spoke French). Still, he probably wished he did. It’s a great thing to have said: it encapsulates one of those truth you always knew but didn’t know you knew.

To illustrate the point: United States Senator ‘Tail-Gunner Joe’ McCarthy was able to convince people that actual Reds were not only hiding under their beds but were also, and secretly, powerful enough to overthrow the government. Joe’s namesake, Goebbels, could convince people that Jews were not only subhuman but also, somehow and simultaneously, shadowy geniuses who controlled all the governments that opposed the Nazis. And let’s not even mention the third Joseph, whom the author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn learnt to regret calling ‘the man with the moustache’, and who had him arrested for the crime of owning a picture of Trotsky.[vii]

Their hard work done, absurdities appropriately believed, it became a straightforward matter for the Joes to convince their followers to enact whatever absurd atrocity they wished.

It's easy enough to confuse humour with intelligence. ‘Those people are just stupid’: that’s a common response to the gullible, the easily-led, the apparently mindless. Yet intelligence is hardly the issue. One striking example from the world of crime:

Gary Michael Heidnick had an IQ of 148: so high, he was about one helium balloon away from genius. With a scant $1500 seed money, he eventually amassed over half a million dollars. That was one really serious bank-balance in the 1970s. Yet Heidnick’s investing skill returned to bite him when he came to trial for kidnapping, rape, and murder. He could not be insane, the prosecutors argued, even though he’d committed extraordinary crimes of the sort that might make a regular person spill their morning coffee on the crime pages while muttering, ‘He must be mad’. Heidnick, it transpired, had not only kidnapped six women but held them in his basement, where he starved, beat, and raped them. The point of this grim story is Heidnick’s defence: None of it was his fault, he claimed. The women had been there when he moved in. Why wouldn’t the court believe him? Stratospheric IQ or otherwise, only a defendant who was completely blind to neon-strip, whirligig, free-jazz horn-honking absurdity could ever make such a claim.

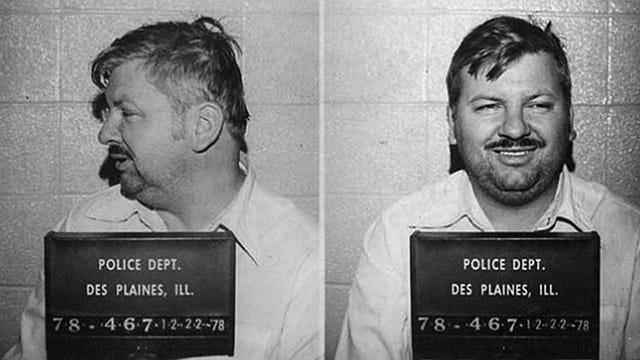

Of course, we hardly expect humour from serial killers. That is not, so to speak, their attention-grabbing quality. But little in the serial killer profile counts against it. You may know that John Wayne Gacy worked as a children’s birthday-party clown. Whether or not he was ever actually funny, it is too late to say with confidence. Dennis Nilson, meanwhile, displayed some gallows humour. He remarked that, when they made a film of his life, they’d have to list the cast in order of disappearance. Nilson, in fact, was caught when the bodies of his victims began to make a stink of the local drains. When he asked a prison warder how to cope without an ashtray, he was told to flush his butts down the toilet. Nilson replied that the last time he did that, he was arrested.[viii]

We don’t expect humour of terrorists, either, or any other breed of fanatic. Fanatics are never funny. Why?: Because they can’t be. There is an obscure psychological phenomenon called ‘intolerance of ambiguity’. Ambiguity is the soil in which jokes thrive. Here’s how most of them work: two stories are proceeding at the same time. You believe that you are hearing Story 1, but, at the end, you discover that it’s been Story 2 all along. It is that sudden recognition of the ambiguity that elicits the laugh. Scientists refer to a ‘conceptual shift, a change in our perception of the state of the world around us’[ix]. Of course, if we know from the beginning that what we’re hearing is a joke, it’s even better. It’s like a whodunit. We know we’re being deceived, so we look forward delightedly to discovering how. The knowledge of the deceit just increases our sense of tension. Humour has been called the sudden release of tension; laughter as the human behaviour that reveals it.

There is a particular type of joke known to comedians as ‘pull back/reveal’. Such jokes work by forcing you to focus on just one aspect of a situation in close-up, before rolling the camera back to make you see the whole thing. The punchline is linked to the set-up at the start of the joke but shows it in context. The most famous example is from Michael Redmond: ‘People often ask me, What are you doing in my garden?’[x] There you have an entire conceptual shift, condensed into a single line.

As ever, we can trace the origins of laughter back into our evolutionary history. ‘The premise of all comedy,’ said Jerry Lewis, ‘is a man in trouble’[xi]. And, we might add, getting out of it (maybe). Most of the human timeline is buried in darkness: that long, long period of threatening geography, scant food, and shoes that gave you splinters. Imagine you’re out one day with two or three fellow hunters. You’re armed only with a sharp rock tied to a stick with a bit of cat. A sabre-toothed tiger suddenly appears, hurtling towards you. The tension could hardly feel greater. Just as you begin to sense the violent end of your own palaeolithic existence, the tiger hits a banana skin and slips into a bog. Turns out the clumsy tiger was no threat after all. Your tension disappears. How do you signal that wonderful feeling? Laughter, of course. The threat transformed into an absurdity. Of course you laughed. People do the same thing today when the fight is over, the tax-returns are filed, the latest round of firings comes to an end and they still have a job.

We can see why the best joke-tellers put in a silent beat before the end of a joke. The dead space helps ramp up the tension a notch. The beat is just time enough to get Story 1 set like spackle in your mind before Story 2 comes bursting out. The punchline has that name for a reason.

The next few short paragraphs simply illustrate the point:

Here is a venerable knee-slapper, which I’ve borrowed from a source I can definitely recommend if you want to read more about this kind of thing[xii]:

‘For forty years I’ve been married and in love with the same woman. If my wife ever finds out she’ll kill me.’

Can you see Story 1 and Story 2? Admittedly, there isn’t much in the way of crime in that joke, so let’s try some a few that cleave a little closer to our subject:

Here is the comedian Anthony Jeselnick (and if you happen to have low tolerance for off-colour humour, you may want to skip this bit): ‘My neighbors in L.A. have got this smokin’ hot 18-year-old daughter. I mean, she’s perfect. But she just got a tattoo of a butterfly over her chest. Which is horrible. Doesn’t she understand how dumb that’s gonna look some day, all stretched out over my lamp?’[xiii]

The joke is criminal almost in more sense than one. Still, it illustrates the point nicely. We believe, at first, that we’re reading a somewhat off-colour story about questionable erotic attraction. That’s enough to make us feel a bit tense. The fact that we are being told this by a professional comedian informs us that there’s more to the story, though, and we get gradually more tense as we wait to learn how we’ve been deceived. And then, well, things turns out to be a whole lot different from what we expected. The joke isn’t much as far as actual wit is concerned, exactly, but it’s not designed that way. It’s designed to shock a laugh out of us.

It goes further, in fact. Jeselnik deconstructs the joke in his very next line: ‘Yeah, that’s a joke. That’s a joke where I’m a serial killer. I’m very open about it. Don’t you dare tighten up on me’. Lose the tension.

‘The richest kind of laughter,’ said the comedian Bill Hicks, ‘is the laughter in response to things people would ordinarily never laugh at’[xiv]. It is, of course, the laughter of those who got through some trauma and came out the other side, more or less unscathed.

Here is Norm MacDonald, from when he used to present Weekend Update on Saturday Night Live: ‘Yippee! Jerry Rubin has died. Oh, I’m sorry, that should say Yippee, Jerry Rubin, has died’. MacDonald was proud of that particular joke, in fact, because of its unusual structure. It has the punchline at the start. The rest of the joke is there to create the necessary ambiguity. Story 2 came first; Story 1 filled in the blanks.

In each of these jokes, the comedian pans back from the deceptive Story 1 and reveals the truth of the matter. Hey, it was Story 2 all along! Tension dissipates. We laugh. Politicians, despots, cult leaders, anyone whose self-image terminates with the suffix -ist: all of them are in the business of selling Story 1. They fear the joke that pans back to reveal Story 2. This is another way of saying that they fear the truth.

Jokes are especially successful when they reveal a truth that perhaps we’d rather not admit, even to ourselves. A good joke can even reveal our own prejudices, cruelties, fears, and – bless the comedians of the world! – make them less shameful. In the context of a joke, we’re allowed to own the shameful feeling and even have it washed (partially) clean.

Bureaucracies, technocracies, ideologies, none of them can withstand the force of a good joke. ‘Make them kind,’ they say: to which we might respond, ‘Kind to whom? To you?’ Not a technocrat in the world wants you to point out that their endless form-filling accomplishes nothing useful. The world is a chaotic mess and you can’t regulate the chaos away. Joke, though, and you are celebrating it.

What’s the job of a fool at court? To speak truth to power, of course, but to do so in a way that makes that truth palatable. That means making power laugh. Truth often comes dressed in motley, with bells on its shoes. ‘Clowns are frightening,’ say those unfortunate souls who suffer from coulrophobia: the fear of clowns. They say it as if they’ve discovered something no one else has noticed. But clowns are supposed to be frightening. Scary is the point. Clowns embody our fears – fear of Others, fear of the truth – and turn them into a target for satire, laughs, mockery. Clowns are serious: deadly serious.

One point more before we go. The Devil, said Thomas Moore, is a proud spirit and cannot endure to be mocked. For that reason, mockery can become a mighty weapon in angelic hands. Here is one reason to oppose censorship. If the intolerant speak only to one another, they never see over the silo-walls of their own opinion. Psychologists have a phrase – ‘reality-checking’. We all need a bit of reality-checking occasionally, particularly if we spend too much time alone or with people who are too similar to ourselves.

There’s a lot to be said for allowing awful people to do their awful laundry in public.

A small degree of conformity is no bad thing: recall that humourless guest at the party, joining the laughter despite failing to understand it. It can be a valuable, to know that we are following society’s rules. Mostly, the rules are there for a reason, even if we don’t know what it is. One close relative of ‘rules’ is ‘the law’. Processes like this, far more than any fear of legal retribution, keep citizens law-abiding.

A couple more jokes, then, to fit the mood. Try to spot Story 1 and Story 2 in each case. But first, please pay attention to the blue buttons below. Annoying, aren’t they? They’re doing it on purpose, you know. Give them a smack. That’ll sort them out.

Didn’t work? Try again. Bop them a few times each. That should do it.

The first example makes Story 1 and Story 2 very overt:

‘When an estate agent gets mugged, do you think the police actually believe their description of what went on? ‘Yes, officer, I was pushed into quite a spacious alley, only two miles from the train station. I was then punched in my face, which still retains some of its original features’. (Sean Mao)

‘My friend Larry’s in jail now. He got 25 years for something he didn’t do. He didn’t run fast enough’. (Damon Wayans)

‘I was walking down Fifth Avenue today and I found a wallet with $150 in it I was going to return it, but I thought that if I lost $150, how would I feel? And I realised I would want to be taught a lesson’. (Emo Philips)

‘An old woman is upset at her husband’s funeral. “You have him in a berown suit and I wanted him in a blue suit”. The mortician says, ‘We’ll take care of that, ma’am,’ and yells back ‘Ed, switch the heads on two and four!’ (Jimmy Carr)

‘My wife and I have just celebrated our thirtieth wedding anniversary. If I’d killed her the first time I thought about it, I’d be out of prison by now’. (Frank Carson)

‘There is nothing like a solemn oath. People always think you mean it’. (Norman Douglas)

‘I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me’. (Hunter S Thompson)

It’s a convict’s first night in prison. He’s sitting with his cellmate when they hear one of the other convicts shout ‘Forty-seven!’ all the other convicts laugh. Then another one shouts, ‘Fifty-four!’ and everyone laughs. The convict turns to his cellmate and asks what’s going on. ‘It’s like this,’ says the cellmate. ‘We’ve all been in here for years and there’s only one joke book in the library. We’ve all heard them so often, there’s no need to tell the whole joke. We just yell out the page number’. So the new convict decides to join in. ‘Twenty-seven,’ he shouts. Total silence. Not a laugh. He asks his cellmate, ‘What went wrong?’ ‘It’s the way you tell ‘em’. (Jimmy Carr)

All pictures courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. References supplied partly from academic habit, but also partly so you can chase up anything you’ve found particularly interesting here.

[i] Mellor, DH: ‘Analytic philosophy’ in Nigel Warburton (ed): Philosophy – Basic readings, Routledge, New york, 1999, pp5-8

[ii] Robert Conquest, quoted in The Naked Jape – Discovering the hidden world of jokes, Penguin, Michael Joseph, London,2006, p221

[iii] Opinion | Bin Laden's Laughter - The New York Times (nytimes.com)

[iv] Carr, Jimmy & Greeves, Lucy, op cit, p7

[v] Carr, Jimmy & Greeves, Lucy, op cit, p196

[vi] Here’s an interesting point: I bet you’ve never met anyone who is happy to admit they have no sense of humour.

[vii] Watson, Peter, The Modern Mind – An intellectual history of the twentieth century, Perennial, New York, 2002, p541

[viii] These stories come from Masters, Brian: Killing for Company – The case of Dennis Nilson, Cornerstone, London, 1995

[ix] Carr, Jimmy & Greeves, Lucy, op cit, p21

[x] The comedian's toolbox | Books | The Guardian

[xi] Project MUSE - Comedy Is A Man In Trouble (jhu.edu)

[xii] How to Write Jokes - Joke Structure Part 2 (linkedin.com)

[xiii] Anthony Jeselnik: Thoughts And Prayers (2015) - Full Transcript - Scraps from the loft I include the full joke only because it is freely available online.

[xiv] Bill Hicks, quoted in Carr, Jimmy & Greeves, Lucy, op cit, p181

This is brilliant. Humour and laughter are always our best defence against authoritarianism. Subscribed!

Made me laugh and me others laugh at the office. Good points too.