AN EXPLOSIVELY VIOLENT FRONTAL LOBOTOMY

Accidents; brain function; personality; the Chicago School of criminology; assault

1848. A railway construction foreman suffered a bizarre accident that changed him utterly. He was working on a railroad project near Cavendish, Vermont. His job was drilling and filling. He poured powder into holes that he made in rocks; covered the powder with sand; tamped it down with a bar called a tamping-iron; fired the fuse. The idea was to destroy the rock for the railroad to come through.[i]

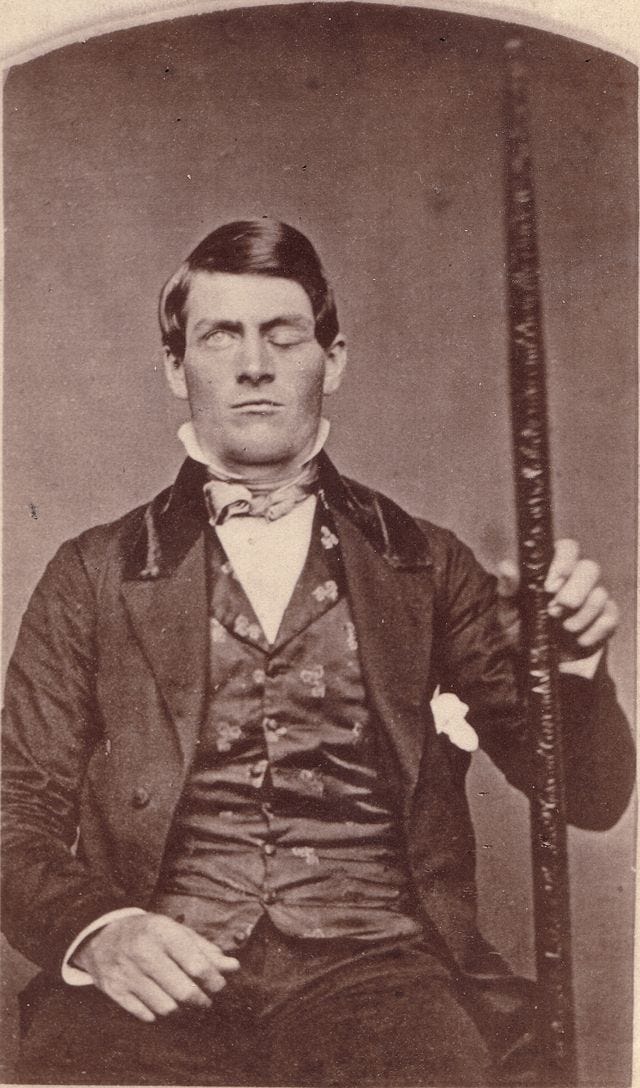

On September 13, at 16.30, handsome, reliable, well-liked, 25 year-old Phineas Gage, “pious and reverent churchgoer”,[ii] did everything correctly except putting sand over the powder. Metal sparked on rock. The iron bar crashed through Gage’s head. The bar was nearly six kilograms in weight, more than a metre in length, more than two centimetres in diameter. It had become smooth with use, which may have been a blessing.[iii] So, too, may the long, tapered end.[iv]

Gage’s colleague, John Harlow, found him lying on his side, convulsively kicking. There was a seven-centimetre hole under Gage’s left eye, and a similar one in the top of his head. Harlow and some co-workers lifted him into a cart and took him to a hotel. The patient sat up all the way.

A local doctor came. He found he could look through the hole in Gage’s skull and see his brain pulsating. When Gage got up and vomited, his brain became even more visible. Half a cupful fell on the floor.[v]

Harlow cut away brain tissue and drained his patient’s wounds. One month later, Gage was sitting up in bed. Before long, he nipped out for coffee.

Naturally enough, Gage’s appearance had changed. A flap of skin grew over the wound in his head, where it pulsed as the blood flowed. He lost the vision in his left eye and developed partial paralysis of the face. More disturbing was the change in his personality. Harlow (using marvellous industrial-strength nineteenth-century prose) described it, twenty years later:

“The equilibrium or balance between his intellectual faculties and animal propensities, seems to have been destroyed. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans for future operation which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn [...] A child in his intellectual capacities but with the general passions of a strong man.”[vi]

Indeed, “his mind was radically changed, so that his friends and acquaintances said he was no longer Gage”.

His employers had once considered Gage the best foreman in the business.[vii] No longer. It was as if they’d employed Henry Jekyll and ended up with Edward Hyde. Gage hit the road, sustaining himself with a jumbled series of strange jobs. He worked in Barnum’s circus, where patrons gasped to see him holding the infamous iron bar. He worked for an American stable and a Chilean coach company. He even tried to start his own business, but health failed him. He moved to San Francisco, where any hope he had of a fresh start were ended. He developed epilepsy and died. The year was 1860, twelve years after Psychology’s most awful accident.

By suffering an explosively violent frontal lobotomy, Gage had proven that character belonged in the brain. The iron bar had destroyed part of the brain above the eyes and behind the bone of the forehead. The area is known as the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. In the process, Gage had lost a mechanism called response inhibition.

Let’s return to those “intellectual faculties and animal propensities”. Symptoms of frontal lobe damage include increased risk-taking, carelessness, unusual sexual behaviour, lack of concentration, and talkativeness. Each one involves temptation: to talk, over-indulge, or simply think about more interesting things. Gage apparently lost his respectable old self and developed a new one - one that looks, to modern eyes, a bit psychopathic, a bit unsteady: in a word, a bit criminal. If law-abiding citizens are those who successfully resist temptation, maybe frontal lobe damage helps explains certain kinds of crime. “[S]elf-regulatory capacity,” some say, “is perhaps the strongest correlate of criminal [...] behavior”.[viii]

All of this, at least, is the story as it is told in Psychology class. With use, it has become as smooth as the tamping-iron itself. At this late date, it’s impossible to know whether Gage really was so very virtuous before the accident, or so criminalistic after it. And we don’t know whether the changes were permanent. Perhaps not: after all, Gage went on to work in a demanding business and even tried to start his own. And where exactly was his injury? There is some debate.[ix] Real life is sometimes less simple than Psychology class.

The prefrontal lobotomy. The operation was pioneered by the Portuguese surgeon and Nobel Prizewinner, Egas Moniz. He cut a small part of the brain out of his psychotic patients. Mostly, their symptoms improved, and never worsened. This was in 1935. In decades to come, thousands of patients around the world tried it, in the hope of returning to normal life. The procedure sounds ghastly. Moniz used an actual blade, attached to a plunger, pushed into the brain. Others preferred to jab an icepick through the bone above each eye and wiggle it back and forth.[x]

I must mention the American neurosurgeon, Walter J Freeman II. Some will tell you he was an eccentric and engaging ambassador for his therapeutic technique. Others will tell you that he was the most notorious medical man since Mengele. Either way, there were reports of “devastating postoperative complications, including intracranial haemorrhage, epilepsy, alterations in affect [mood] and personality, brain abscess, dementia, and death”. In one case, Freeman was posing for a photograph while his patient haemorrhaged and died on the operating table. His reputation was not helped by stories of colleagues coming into the room to find unconscious patients with icepicks lodged in the orbit. The final blow may have been the lobotomy’s demonic role in fiction by Tennessee Williams, Sylvia Plath, Joyce Carol Oates, and Ken Kesey.[xi] By the 1980s, the procedure had effectively vanished from the medical repertoire.

In Argentina, the lobotomy may well have been used for explicitly political purposes. One victim was Eva Peron, the president’s wife. Officially, it helped alleviate the pain caused by cancer. Her medical team has since suggested that it was really motivated by her increasingly-belligerent political speeches. Her husband may have started to think of her as a threat that he had to nullify.[xii]

Hideous those these stories are, they helped psychologists create remarkable maps to indicate which parts of the brain are responsible for what The technical term for that is ‘localisation of function’.

The Chicago School of criminologists mapped crime onto anatomy of the modern city, which they saw as a series of concentric zones, some predictably more dangerous than others. Perhaps they could have transposed their logic to the anatomy of the brain. Its structures become newer, and more law-abiding, the further they lie from the centre. You may have heard psychologists refer to the ‘reptile brain’. That’s the oldest of the three parts (Chicago professors might have thought of it as the Loop). It controls breathing, heart rate, and other basic functions (in the same way, the Loop puts the go in Chicago). The limbic system comes next. Its name comes from the Latin for border or limit. The system does indeed mark a border, in the brain as much as the city. It’s the Zone of Transition, handling emotions like shock, fright, and anger. Although they are vital for survival, civilised society needs to keep a check on them. That job falls to the outermost layer, which is called the neocortex. It includes the frontal lobes. There are well-developed pathways between the limbic system and the neocortex (think of Chicago’s L, or rapid transit system). The frontal lobes are used whenever you co-ordinate information, and decide what to do with it. The prefrontal cortex, right behind the forehead, is involved in concentration, conscientiousness, maybe moral reasoning. These are called “executive functions”.[xiii] Like other executives, they belong in the commuter zone.

Evolution, then, did not change one type of crude, primitive brain into another, more civilised and intelligent than before. Rather, it dumped a second brain on top of the first. If animal emotions sometimes override our logic, that’s partly because ‘evolution has left a few screws loose between the neocortex and the hypothalamus’.[xiv] The screws are looser, of course, in some than others

.

The frontal lobes are involved in response inhibition.[xv] Not to get too technical about it, ‘response inhibition’ means damping the drives of the limbic system and remembering the rules. Have you ever known a person who developed dementia, and seemed to get angry or violent for no reason? Their frontal lobes could no longer suppress the demands of the reptile inside.[xvi] You may see something similar in binge drinkers, and for similar reasons.

You and I are quite good at response inhibition. Being the well-educated, civilised people we are, we tend not to run away when we get scared, or punch strangers in the face when they push in front of us in the queue. It’s not that we don’t, in a sense, want to. Our limbic system tell us to react with fight, or anger. But that neocortex inhibits the response. It tells us to obey the rules: go and sit the exam that scares us; leave the pushy shopper unmolested. It is because we can do response inhibition that we remain on the more desirable side of the prison walls.

Frontal lobe damage, meanwhile, can lead to some truly startling behaviour.[xvii] We can begin faintly to understand why the serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, army medic and chemist’s son, drilled holes into the heads of certain victims, and poured caustic chemicals inside.[xviii] It was his grotesque, Frankensteinian effort to create “zombie sex-slaves”.[xix] More on that in an upcoming newsletter.

It is the right time to blip or beep a bright blue button below. Thank you!

[i] Grieve, Andrew W: “Phineas Gage – ‘The man with the iron bar’”, Trauma, 2010, 12, pp171-4

[ii] Koskoff, Yale David MD & Goldhurst, Richard: The Dark Side of the House, Leslie Frewin, London, 1969, pvii

[iii] Grieve, Andrew W, op cit

[iv] Guidotti, Tee L: “Phineas Gage & his frontal lobe – The ‘American crowbar case’”, Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, Vol 67, Issue 4, 2012, pp249-50

[v] Dr Williams, quoted in Grieve, Andrew W, op cit, p172

[vi] JM Harlow, quoted in Grieve, Andrew W, op cit

[vii] JM Harlow, quoted in Koskoff, Yale David MD & Goldhurst, Richard, op cit, pviii

[viii] Jorgensen, Cody, Anderson, Nathaniel F & Barnes, JC: “Bad Brains – Crime & drug abuse from a neurocriminological perspective”, American Journal of Criminal Justice 41, 2016 p62

[ix] V Grieve, Andrew W, op cit; Van Horn, John Darrell, Irimia, Abdrei, Torgerson, Carinna M, Chambers, Micah C, Kikinis, Ron & Toga, Arthur W: “Mapping connectivity damage in the case of Phineas Gage”, Plos One, May 16, 2012, Available at https://doi.org/10.137/journal.pomne.0037454, Accessed 27th August, 2019

[x] Gazzaniga, Michael S, Ivry, Richard B, Mangun, George R: Cognitive Neuroscience – The biology of the mind, 4th edition, W W Norton, London, 2014,, pp564-5

[xi] Caruso, James P & Sheehan, Jason P: “Psychosurgery, ethics, & media – A history of Walter Freeman & the lobotomy”, Neurosurgical Focus, 43(3): E6, 2017

[xii] Caruso, James P & Sheehan, Jason P, op cit

[xiii] Crews, Fulton T & Boettiger, Charlotte Ann: “Impulsivity, frontal lobes, & risk for addiction”, Pharmacology, Biochemistry & Behavior, 2009, Vol93(3), pp237-47

[xiv] Arthur Koestler, quoted in Wilson, Colin, A Criminal History of Mankind, Granada, London, 1984,, p49

[xv] Sharp, DJ, Bonnelle, V, DeBoissezon, X, Bekmann, CF, James, SG, Patel, MC & Mehta, MA: “Distinct frontal systems for response inhibition, attentional capture, & error processing”, PNAS, March 30, 2010, 107(13) pp6106-6111; Hampshire, Adam: “Putting the brakes on inhibitory models of frontal lobe function”, Neuroimage, 2015, June: 113, pp340-355

[xvi] Budson, Andrew E: “Don’t listen to your lizard brain”, Psychology Today, Dec 3, 2017

[xvii] Briken, P, Habermann, N, Berner, W & Hill, A: “The influence of brain abnormalities on psychosocial development, criminal history, & paraphilia in sexual murderers”, Journal of Forensic Science, 50, 2005, 1204-1208

[xviii] “Psychiatrist: Jeffrey Dahmer did lobotomies on drugged victims”, AP News, January 19, 1992, Available at apnews.com/9d6f4ef8a38401527aad1af9ef45134c, Accessed 13th September, 2019

[xix] Jentzen, Jeffrey M: “Micro disasters: The case of serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer”, Academic Forensic Pathology, September 7(3), 2017, pp444-452

Great read! Thanks for highlighting lobotomy, did you ever write that article about Dahmer and Zombie Sex Slaves?

Thank you for the restacks!