THE PSYCHOLOGY LESSON OF DR TULP

Robbery; surgery; execution; anatomy; painting; human brains and human hands

Amsterdam, 1632: Two petty criminals attempt to steal another man’s cloak. The incident is evidently quite violent. One of the robbers, variously known as Adriaen Adriaensz, Adriaan Adriaans, Adriaen Adriaenszoon, and Aris Kindt, is captured, convicted, and hanged for ‘grave assault and battery that endangered the life of a man…’ Adriaensz is a repeat offender who has recently assaulted a prison warder. The court offers him no mercy. He is hanged in a public place, as a warning to others. The body is cut down immediately after death, to prevent depredations not only by birds but also by superstitious passers-by who attribute magical properties to parts of a hanged man’s corpse.

The body is given to the Amsterdam Surgeons’ Guild. It is anatomised by Dr Nicolaes Tulp (whose real name is Pieterszoon). The Church allows anatomists to dissect only a single corpse every year. This small concession to medical learning[i] came after an entire millennium during which dissection was illegal altogether.[ii] Surgeons are allowed only the bodies of executed criminals, suicides, or bastards.[iii] Tulp’s anatomy lesson is commemorated by a whippersnapper named Rembrandt van Rijn. His painting is no easy thing to write about in a short newsletter: it constitutes a whole sub-field of Rembrandt studies and was once the sole subject of a 400-page volume.[iv] You’ll be pleased to know that I’m going to keep this newsletter below 3000 words.

Rembrandt was carrying out his first big commission after moving to Amsterdam from Leiden. Six guild members in addition to Tulp seem to have splashed out to have their faces featured in a painting that celebrated their participation in the intellectual life of the city.

And what a city it was! Amsterdam had some claim to being the most important city in Europe. It was, after all, the world centre of capitalism. That meant riches (at least for a few), and, perhaps more important, revolution in the internal life of its citizens. Capitalism, that shiny new idea, went hand-in-glove with modern western individualism. Dutch art was new because the individual was new.[v]

A time-travelling art lover wandering into seventeenth-century Amsterdam from, say, sixteenth-century Italy, would have been struck by its novel topics and techniques. Religious subject-matter had mostly given way to secular. Dutch art dealt with landscape, architecture, everyday life as it was lived. It emphasised space, light, the physicality of objects. A jug painted by a Dutch artist looked like something you could pick up and heft. Perhaps you could even crack someone over the head with it.

No wonder – in the era of the Scientific Revolution, the always-fashionable Dutch had been among the first to replace Divine Authority by ‘experience, experiment and observation’.[vi] Theirs was an art that got ‘back to the facts […], unaffected by custom or convention’.[vii] We still know exactly what every important Dutchman or -woman looked like, how they held themselves, how they dressed. You could recognise anyone from a painting by Frans Hals (1580-1666), and not just by the ruffles and big hat. You could recognise a sheep from a painting by Paulus Potter (1625-1654), too.

Seventeenth century painters dragged blood, muck, and truth onto the canvas. For down-and-dirty, dramatic realism, Caravaggio (1571-1610) provided endless inspiration. If his hands were often red with paint, well, you might not ask what it was mixed with. Caravaggio’s world was altogether different from the scrubbed and shiny world of his predecessors. Caravaggio gave you the facts in all their actuality: dirty feet, bitten fingernails, weighty objects, uneven lighting. Rembrandt, among others, was impressed (in fact, his teacher’s work was once called ‘Caravaggio in a teacup’[viii]). Look at the ‘Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp’ and the inspiration is right there in front of you.

If Amsterdam’s painters were all in favour of down-and-dirty realism, its anatomists were no different. They too had learnt to focus on reality and the way things actually looked. This too was something of a revolution. Up until then, Europe’s universities had been dominated by the Scholastics (or Schoolmen) to whom the evidence of their own eyes was less important than the teachings of authority. Students watched the anatomists disassembling the cadavers of executed criminals, while their lecturers sat away to one side, reading aloud from Claudius Galen’s ancient texts. It often happened, of course, that the evidence of the students’ eyes contradicted the texts. That, however, did not prove that Galen was untrustworthy - it proved that the students’ eyes were. Even when medieval anatomists performed their own dissections, ‘what they found (or thought they found) was what Galen had told them to find’.[ix] Such was the weight of authority. Like Aristotle, who had dominated the curriculum for 400 years,[x] Galen, the first modern physician, was always right, even when he was clearly wrong.

The Flemish anatomist, Andreas van Wezel, (known as Vesalius,) was responsible for ‘the first science grounded in what we would now call facts’.[xi] Vesalius made a name for himself by drawing proper, realistic, anatomical charts. Indeed, he constructed whole series of them, more accurate by far than anything that had gone before.[xii] He based them on his own dissections of criminals. In doing so, he realised that the great master of human anatomy, Galen, had never dissected an actual human corpse. Goats, pigs, cows, and dogs, yes. Human beings, no. Vesalius not only knew what his eyes were telling him, he was inclined to believe them. His book, De humani corporis fabrica, appeared in 1543, which was the same year in which Copernicus showed that the sun, rather than the Earth, was the centre of the solar system. Respect for antiquity had weakened at last. Scientists everywhere were the beneficiaries. Not that it helped Vesalius very much. Something of a martyr to science, he suffered as a consequence of his disagreement with Galen. He was made to give up his university position and burn his unpublished work.[xiii]

Vesalius’s book is a long insistence on the vital importance of empiricism – that is, the evidence of one’s own senses. ‘Insistence’ is the right word, since this seemed a matter of the very highest importance. Vesalius, like Tulp after him, ‘believed the practice of anatomy led to greater knowledge of God, since the body is a product of Divine creation’.[xiv] There was a holy quality to scientific knowledge.

If Galen’s treatises contained no illustrations, Vesalius, by contrast, insisted on them (that word again). He insisted, too, that they must be made and printed by the finest craftsmen available – blockcutters from Venice; draftsmen who’d worked with Titian. The frontispiece shows Vesalius himself dissecting a human forearm. As he does so, he looks directly towards us, the viewers. This is a picture about observation, which has become of the foundations of modern science.

Rembrandt – this ‘great poet of the need for truth’ and ‘appeal to experience’[xv] - shows Dr Tulp displaying to his fellow guild members the muscles in Adriaen Adriaensz’ flayed forearm. (Dissection of the arm may have been a symbolic punishment for the crime of theft.[xvi]) The nod to Vesalius could hardly have been more explicit. It implied that Tulp was Vesalius’ successor, if not his actual reincarnation. Some authors have argued that Tulp sometimes thought of himself as Vesalius Reborn.

For sure, Tulp was a remarkable fellow. He published a treatise on monsters, discovered the human lymphatic vessels, and wrote the first European description of a chimpanzee. He also recommended drinking fifty cups of tea a day. Rembrandt’s portrait shows him in one of those rare moments when he was not boiling a kettle. In flexing his left hand, he uses the same muscles he has just uncovered in Adriaensz’ arm. On the dissection table stands a book: probably the treatise by Vesalius. Tulp, too, is emphasising the vital importance of proper observation, made of the real world, as it was and not as some authority claimed. Rembrandt, meanwhile, shows us the dignity of science in general and surgery in particular. His attitude is of a piece with the dominant Protestant ideology.[xvii] ‘True understanding’ could be had only as a consequence of ‘direct inspection’.[xviii]

Evidently, the pose was a most deliberate choice. Anatomy lessons weren’t quite like that. Surgeons always started with internal organs – the stomach and perhaps the brain – and only later proceeded to extremities like the forearm. That was because corpses, in those centuries before refrigeration, tended to rot. For the same reason, dissections always took place in winter.

Although Rembrandt shows only seven onlookers, these dissections were very much social occasions: they took place in an actual anatomical theatre, which had its own lights and seating arrangement. Anything up to 500 spectators might come to watch and learn.[xix] Apparently, ‘even ladies were invited’.[xx] The spectators’ entrance fees were enough not only to pay the surgeons, but also provide a banquet afterwards. There might be flute music.

Legal ordnances ‘explicitly prohibited the audience from speaking or laughing during dissections, although they were permitted to ask questions as long as these were of a ‘decent and serious nature.’ It was a decent and serious affair all round in fact: audience members could be fined for stealing internal organs.[xxi]

You and I, as viewers of the painting, take the place of Tulp’s audience. Indeed, we make the whole affair worthwhile, since a lesson without students is futile. Through eye contact, other guild members draw us into the picture. We recognise their expressions: appreciation, pride, puzzlement. Rembrandt, in other words, manages to show us their minds. This is something quite new in art.

There is another way to read the painting. To know oneself is to know God, some scholars liked to claim. Protestantism recognised two holy books – the Bible and God’s universe. This second book included an entire chapter about the human body. Anatomists were in the business of reading that chapter and translating it for the benefit of their congregations. Remember, Tulp is demonstrating the movement of the human hand. We know, from notes made by one of his students, that he liked to ‘use the dissection of the forearm […] as an exemplum of the God-created ingenuity of the human body’.[xxii]

Our hands help to make human beings unique. Indeed, its evolution was one of the most important steps towards human consciousness.

Human hands have a quality known as opposability. Full pad-to-pad contact between the thumb and other digits is unknown in other primates: not even chimpanzees possess quite the ability that you and I take for granted. That, plus another, related ability – to move the fingers independently of each other – gave us an illuminating new tool with which to explore, adapt, and even build our world. The hand constantly reinforced the distinction between what was Self and what was Other. One eminent neuroscientist suggests that the hand ‘took us over the threshold dividing consciousness from self-consciousness and unreflective, instinctive behaviour from true agency’.[xxiii] The historian, Simon Schama, alludes to ‘the divinity of dexterity’.[xxiv]

Tulp, then, is shown using his God-given reason to achieve an understanding of God’s work. Adriaensz, meanwhile, who has just come down from the gallows, looks like Christ taken down from the Cross. He is even dressed the same way. Much of the light in the painting seems to emanate from his pale body. Tulp even draws attention to Adriaensz’ wounds or stigmata, in much the same way that Mary and the angels usually do in deposition paintings. Above his shoulder is a scallop shell, symbol of baptism and rebirth in Christ.[xxv]

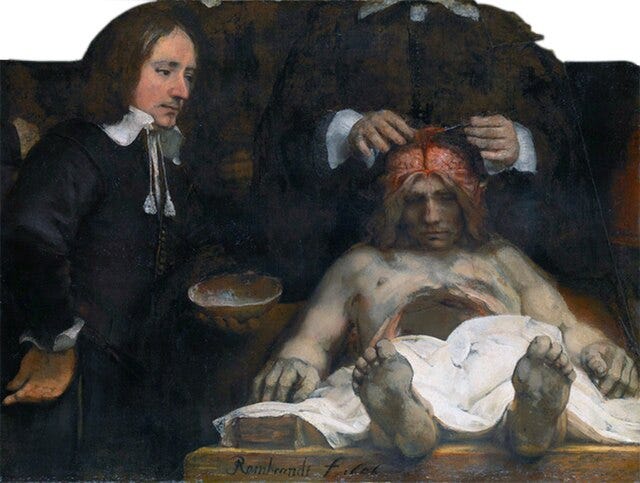

Rembrandt’s other great anatomy-lesson painting (‘The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Deijman’ 1656) is one of ‘magnificent strangeness’.[xxvi] The criminal’s corpse is presented feet-first to the viewer in a reference that every Art History undergraduate must surely recognise: Andrea Mantegna’s ‘Lamentation over the Dead Christ’ (1500). Deijman has followed protocol more faithfully than Tulp. He has already opened and eviscerated the stomach and is currently hard at work on the brain. He employs his forceps carefully, ‘as though opening a holy book’.[xxvii] Of course, that’s exactly what he’s doing.

If dexterity is ‘divine’, what can we say about human reason, knowledge, and understanding? Psychology is the greatest marvel of God’s handiwork. Given the high position in which the painting was hung, Rembrandt evidently thought of the anatomy theatre as a kind of church and the painting as its altarpiece. The anatomist himself ‘stands, paternal and godlike, over the head of the miscreant, lovingly peeling back the dura matter membranes and separating the two cerebral hemispheres as if administering a benediction’.[xxviii] What could be clearer than that?

Revolutionary though Vesalius’ work was, it did have one major flaw. His pictures of the brain were, to put it kindly, not the best. He dissected it by sawing off slices progressively, one after another, working from the crown towards the jaws. The brain decays quickly when exposed to air, and cutting, of course, tends to mangle its soft tissue. The further Vesalius descended, the less accurate his drawings became.

In part, his motivation was nothing less than to locate the human soul. Galen had claimed there was a network that transformed the ‘vital spirits of the blood into the animal spirits’ and thereby allowed movement. He had located the spirits in the brain’s ventricles – three supposedly spherical holes in the brain’s white matter. Vesalius couldn’t find them. He suspected something heretical - the biological matter of the brain itself might be the best place to hunt for human psychology. The spirit was actually flesh. Worried about backlash from the Church, Vesalius decided at length to venture no further.[xxix]

The owner of the brain that was dissected by Dr Deijman had been one Joris Fonteijn (1633/34-1656), known as The Black Cat. Like Adriaensz, he was an habitual offender, found guilty of robbing a textile store and threatening witnesses with a knife. He was hanged on 28th January and dissected on 29th. He would be forgotten today if Rembrandt had not shown him to us in the most undignified moment of his afterlife.

All images courtesy of WikiMedia Commons. References provided partly out of academic habit, but also so that you can chase up anything that seems particularly interesting.

[i] Conaty, Siobhan M: ‘Rembrandt’s anatomical portraits’, Journal of Humanities in Rehabilitation, 20th June, 2016, available at Microsoft Word - Rembrandt's Anatomical Portraits.docx (jhrehab.org)

[ii] Brenna, Connor TA: ‘Bygone theatres of events: A history of human anatomy and dissection’, The Anatomical Record, 22 September 2021

[iii] de Paz Fernandez FJ: ‘Rembrandt’s Anatomy Lessons’, Neurosciences & History 2018, 6(1) pp1-9

[iv] Schwartz, Gary: The Rembrandt Book, Abrams, New York, 2006, p166

[v] Siedentrop, Larry: Inventing the Individual – The origins of Western liberalism, Allen Lane, London, 2014

[vi] Clark, Kenneth: Civilisation – A personal view, Folio Society, London, 1969/1999, p144

[vii] Clark, Kenneth, op cit, p154

[viii] Levey, Michael: A Concise History of Painting from Giotto to Cezanne, Thames & Hudson, Loindon, 1974, p194

[ix] Wootton, David, The Invention of Science – A new history of the Scientific Revolution, Allen Lane, St Ives, 2015, p183

[x] Barbour, Ian: Religion & the History of Science – Historical & contemporary issues, HarperCollins, London, 1997, p4

[xi] Wootton, David,op cit, p302

[xii] Zimmer, Carl: Soul Made Flesh – The discovery of the brain & how it changed the world, William Heinemann, London, 2004, p19

[xiii] Brenna, Connor TA, op cit

[xiv] Mitchell, Dolores: ‘Rembrandt’s “The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp” – A sinner among the righteous’, Artibus et Historiae, vol. 15 no30, 1994, p146

[xv] Clark, Kenneth, op cit, p152; 150

[xvi] de Paz Fernandez FJ, op cit

[xvii] de Paz Fernandez FJ, op cit

[xviii] Schama, Simon: Rembrandt’s Eyes, Allen Lane, London, 1999, p342

[xix] de Paz Fernandez FJ, op cit

[xx] Marcus EL, Clarfield AM, quoted in Conaty, Siobhan, op cit, p2

[xxi] de Paz Fernandez FJ, op cit, p3

[xxii] Schama, Simon, op cit, p342

[xxiii] Tallis, Raymond: Aping Mankind – Neuromania, Darwinitis & the misrepresentation of humanity, Acumen, Durham, 2011, p217

[xxiv] Schama, Simon, op cit, p603

[xxv] Schwartz, Gary, op cit, p164

[xxvi] Schama, Simon, op cit, p603

[xxvii] de Paz Fernandez FJ, op cit, p8

[xxviii] Schama, Simon, op cit, p604

[xxix] Zimmer, Carl,op cit, p21

Fascinating!

Fantastic and insightful column again! Really interesting to see that habitual criminals were often setenced to death as if they were incorrigible. Secondly, there seems to be a strange step in studying such bodies, because studying them as a way to understand normal versus criminal bodies suggests that the difference between normal and criminal people is not biological/physical -- otherwise why would studying these bodies help cure normal bodies.

Secondly, there is a really interesting discussion of Vaselius in Laqueur's Making Sex. In one of the chapters he suggested that Vesalius very much drew what he thought rather than what he saw. This chapter deals with sex and the anatomy of men/women and posited that Vesalius and his contemporaries saw -- ovaries and testes referred to by the same name and Vesalius drawings of female genitalia look like inverted penises. It is interesting to think that even for someone committed to observation assumptions about how the world is, can affect what one sees.